Dinger's Aviation Pages

RAF fighter’s black and white undersides – WHY?

During the period of the Phoney War and into the Battle of Britain British Spitfires, Hurricanes, Defiants and the fighter version of the Blenheim sported a half black/half white colour scheme to their undersides. Why was this? When was it used and why was it stopped?

In the 1930s, the Observer Corps had difficulty distinguishing between the Hawker Hart bomber (left) and the Hawker Demon fighter (right) during training exercises.

From 1925, the job of tracking and reporting any enemy aircraft over the United Kingdom was done by the Observer Corp. During the early 1930s their job of reporting on the yearly air exercises was made more difficult because the Hawker Demon two-seat fighter was adopted as a counter to the high speed of the Hawker Hart bomber. These aircraft were virtually identical and almost impossible to tell apart, especially at height through binoculars. Matters were made worse by the adoption of the Hawker Fury single-seat fighter which looked similar to both the Demon and Hart. Requests by the Observer Corp for some sort of markings to help them identify the fighters from the bombers seem to have been ignored, perhaps because both fighters and bombers were grouped together under the single command of "Air Defence of Great Britain" (ADGB), and the needs of neither the bomber nor fighter branches was seen as paramount. Then in 1936, Hugh Dowding took over as head of ADGB briefly before it was split up into Bomber and Fighter Command. After the split, Dowding became head of Fighter Command. After the 1937 Air Exercises again threw up the same request from the Observer Corp for a means of identifying friendly fighters, Dowding choose to act. Although the Hart, Demon and Fury were scheduled to be replaced by more modern monoplanes, one of the new types selected for reequipping Fighter Command was the fighter version of the Blenheim bomber. Thus the same issue would reappear in trying to differentiate between fighter and bomber Blenheims on air exercises. Radar was starting to be used to detect aircraft approaching Britain, but that radar coverage only worked looking out to sea. Once over land the tracking and detection of enemy bombers was still done by the Observer Corp.¹

The Bristol Blenheim. The only difference between the bomber version and the fighter version was a gun-pack carried under the belly of the fighter version. It would have been almost impossible for the Observer Corps to distinguish between the two at height during air exercises where it would have been the duty of the fighter verson to intercept the bomber version. Hence the need for some sort of distinguishing markings.

Thus, in September of 1937, two Blenheims were allocated for trials of various experimental colour schemes to aid identification. It was soon established that having the underside of one wing painted white and the other black gave the best results, especially when viewing aircraft at great height through binoculars, or if caught in the beam of a searchlight at night. It should be remembered that at this stage all of the new British monoplane fighters, Spitfires, Hurricanes, Blenheims and Defiants, were expected to be able to fly and fight at night. Indeed, it was anticipated that they would spend up to 50% of their time doing so in wartime. So the new identification scheme needed to work for aircraft illuminated by searchlights.

The first Spitfires and Hurricanes were delivered with silver undersides with roundels.

The new scheme was first tried out during the air exercises that ran in early August of 1938, apparently with success. In September the Munich Crisis occurred and the new identification scheme was ordered to be used on fighter aircraft, with the underside of the port wing painted black and the starboard white. Those Spitfires, Hurricanes and Blenheims already in service had been delivered from the factory with brown and green camouflaged upper surfaces and silver undersurfaces. Older, all-silver, Gloster Gauntlet and Hawker Fury and Demon biplane fighters had their upper surfaces quickly camouflaged in brown and green and the black and white scheme applied to their undersides.

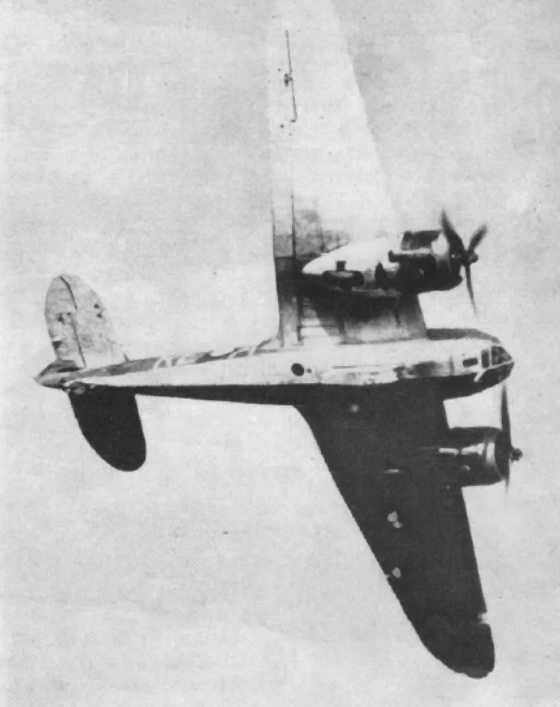

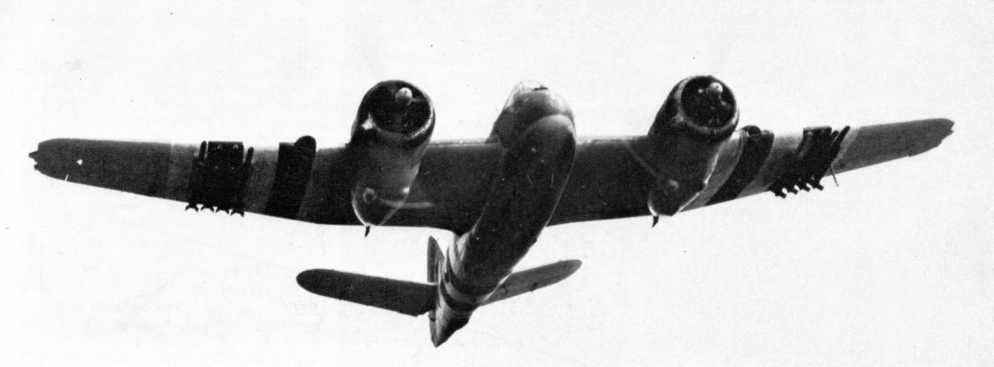

A Blenheim IF fighter (identified by its belly gun pack) with half black / half white undersides.

There was an issue with ailerons. Most RAF aircraft used “Frise” type ailerons, invented by Leslie Frise of the Bristol Aircraft company. These enabled lighter control with less force needed on the control column. The hinge of Frise ailerons was set back from the front of the aileron, with the weight in front of the hinge balanced with the weight behind the hinge. On light-weight, fabric-covered ailerons the application of layers of paint to the larger surface area to the rear of the aileron hinge-line could throw it out of balance, meaning they had to be re-balanced with small lead weights added in front of the hinge. When the instructions to adopt the new colour scheme went out it specified that no painting of ailerons should occur that required them to be re-balanced. This meant that the ailerons were often left in their original silver finish underneath. This colour difference has often been misinterpreted in black-and-white photos as the aileron being painted white, and sometimes that the opposite aileron was painted black. The issue of aileron colours was different in the case of the fighter version of the Blenheim. All Blenheims left the factory configured and painted as bombers with all-black undersurfaces. Those selected to be used as fighters were converted at RAF Maintenance Units with the fitting of underbelly gun packs and then the underside of the starboard wing was painted white. Because of the order that no painting should occur that led to re-balancing of the aileron, this meant that some Blenheims kept the underside of the starboard aileron black.

Blenheim IF fighters of 29 Squadron in August 1939. You can see that the airborne Blenheim has a black starboard aileron. This was because Blenheims left the production line with all-black undersurfaces. The restriction on repainting ailerons meant that when repainted with Fighter Command starboard white undersurfaces the aileron was often left black.

The progression of Spitfire underside colour schemes in Northern Europe from 1938 until 1944 (gif animation).

Servicing a Spitfire with black and white undersides.

With the instructions for changing the colour scheme going out in tersely worded signals, with no accompanying diagrams, there was scope for different interpretations. It seems some aircraft got their starboard wing undersides painted black instead of the port wing. One explanation of this was that the top camouflage pattern was supposed to be a “mirror image” on odd and even serialised aircraft and there might have been an assumption that the same applied to the under-surface paint scheme. There was also confusion about what to do about under-surface roundels and serial numbers. A signal in June 1938 specified that under surface roundels should be painted over, except for any aircraft destined to serve in the “Field Force” (be sent to France in the event of war). Generally, Fighter Command deleted the underwing serial numbers from its aircraft; confusingly, Bomber Command seem to have kept the white serials on the underwing of their Fairey Battle and Bristol Blenheim bombers (which had all-black under surfaces) until the outbreak of war.

There was muddle about just where the divide between black and white should be and if the undersides of the fuselage should be painted black and white as well; there were many variations. On the 27th of April 1939, what had previously been instructions for Fighter Command only were formalised in an Air Ministry Order (AMO) that covered all RAF and Royal Navy aircraft (AMO A154/39). This standardised the dividing line between black and white for fighters. The exact wordings were:

"The lower surface of the starboard plane and half the surface of fuselage to be painted white. The corresponding port side to be painted black."

The order also specified that underwing roundels were not to be carried by fighters. The instructions were regarded as "secret" (they contained a list of squadron identification codes), so were not relayed to the aircraft industry who seem to have carried on delivering fighter aircraft with the silver undersurfaces to the nose and tail for some time.

The black paint used was called "night"; it had a component of dark ultramarine blue that could make it appear a very dark grey. It was prone to chipping and flaking off. The subject of the paints used by the RAF during WW2 is a rabbit hole that research on the dug-up remains from crash sites is still adding to. To keep this article short, I'll not go into any great detail about the paints used.

The prototype Gloster F9/37 twin-engined fighter with port black and starboard white wing undersurfaces. It has serials of the opposite colour under each wing. The underside of the fuselage fore and aft of the wings was silver, as were the undersides of the tailplane and engine nacelles forward of the wings. You can see the black paint was prone to flake off.

Fighter Command stuck with the black/white underwing scheme until the end of the Dunkirk evacuation. However, the Gladiator and Hurricane fighters sent to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force Air Component (BEFAC) had alarming instances of “friendly fire” from French forces. They made sure that underwing roundels were carried; that on the starboard black wing sometimes having an outline of white or yellow to make it stand out. It seems that at least one Hurricane Squadron in France (No 1 Squadron) experimented with light blue under surfaces, to better hide their approach to enemy aircraft. When the Blitzkrieg broke in May 1940, British-based fighter squadrons started flying sorties over Belgium and France. This opened them up to the same sort of friendly fire incidents as the BEFAC squadrons had endured; so on the 15th of May the order went out to paint roundels under the wings of all Fighter Command aircraft. On the 4th of June, another order went out to surround the roundel on the black wing with a circle of yellow, making sure that it did not impinge on the aileron. It seems some squadrons may have already anticipated this with a thin outline of yellow or white.

There were criticisms raised about the black/white scheme. The obvious problem was that it made RAF fighters more visible when approaching enemy aircraft from above, sometimes losing the element of surprise. There were also issues that in certain light conditions, at dawn and dusk, one side of the wings could be thrown into shadow, confusing the correct identification of aircraft as friendly. The white underside of one wing was also seen as a hindrance to aircraft tasked with night-time interception, making them more visible (this was before the formation of dedicated night fighter squadrons).

This Hurricane (P2627) was photographed in Egypt in 1940 shortly after arriving, still with Northern European markings. It illustrates a mixture of standards. A black port wing with a roundel thinly outlined in yellow. What looks like a white starboard underwing and nose (the nose was probably repainted when the large tropical filter was fitted). The roundel under the starboard wing has been overpainted but is still discernable. The underside of the rear fuselage looks to be a different colour, maybe silver or "sky".

On the 6th of June 1940, two days after the end of the Dunkirk evacuation, the order went out to paint the under surfaces of all Fighter Command aircraft the colour “sky”. This was a pale duck-egg green shade. There were shortages of the official colour at first, leading to it being mixed from whatever colours were available, leading to light blue, pale blue and duck-egg blue shades being applied as well. It seems that at some airfields no one was sure exactly what colour “sky” was meant to be; it was only when new aircraft were delivered from the manufacturers with the regulation colour applied that they had a guide to what colour to mix. Some of those who wrote about the colour “sky” in later years remembered it as being somewhat darker in that summer of 1940 than later on. Roundels were to be painted over. This meant the order of the 4th of June to paint yellow outlines to underwing roundels on the port wing was only in force for 2 days! Then, on the 1st of August 1940 “type A” roundels were reapplied to the underside of wings, often this was a smaller roundel out towards the tip of the wing although it was later standardised as a larger roundel at the halfway point opposite the ailerons.

Westland Whirlwind fighter with "sky" undersides and the port wing painted black. Note that the overall diameter of the port underwing roundel with its outer yellow ring was the same as the starboard one without a yellow outer ring.

Sky was a duck-egg green colour that had been adopted by Sydney Cotton to apply to the aircraft he used for clandestine photo reconnaissance flights over Germany in the late 1930s. It did not look out of place as a colour to paint a civilian aircraft while at the same time it blended in with the low cloud and industrial haze that predominated in Northern Europe. When Cotton set up the dedicated photo reconnaissance flight at Heston it was one of the colours adopted for applying to the Spitfires it used. It was also adopted as the colour for under surfaces by the squadrons flying Blenheims in the reconnaissance role over France and Belgium. The term “eau de nil” was often associated with the colour. “eau de nil” means “water of the Nile” and it was meant to describe the pale grey-green-blue colour of the Nile as it flows through Egypt. It was a very fashionable colour in the 1930s. The theory was that its combination of the blue of the sky and green of foliage made it the most “pleasing” colour to the eye and had a soothing effect. It was widely used in train, bus and aircraft interiors and the waiting rooms at stations and doctors. It was the colour used for the interior of most RAF motor vehicles and was used inside many RAF buildings. It was a natural reference colour for describing “sky” which was a slightly lighter shade.

For some reason this de Havilland Don trainer/communications aircraft has its port wing underside painted black like the aircraft of Fighter and Army Cooperation Command. RAF training and transport aircraft usually had yellow undersides.

The order to paint undersides “sky” was done either at the instigation of or with the approval of, Hugh Dowding. By early June of 1940, it must have become obvious that the main air battles of the summer were going to take place in daylight and that German bombers were being escorted by nimble single-seat fighters (something that had not been anticipated in pre-war planning). So the switch to a colour scheme meant to mask the approach from above of British fighters was entirely justified.

The pace of air combat over Britain slackened in October 1940 (the Battle of Britain is usually said to have ended on the 31st October). On the 27th of November 1940, the order went out that fighter and Army cooperation aircraft were to have their port wings painted black again. This time the starboard wing and undersurface of the fuselage would stay in the “sky” colour. Roundels would be carried under the wing, with the roundel under the port wing outlined in yellow. The black paint used was a “semi-permanent” distemper type paint meaning it could be removed more easily. Just why the black port underwing made a reappearance at this time is open to interpretation. Hugh Dowding had been removed as head of Fighter Command only a few days before, to be replaced by Sholto Douglas. One suggestion is that Douglas had the change introduced as part of stamping his authority on his new command. Most sources say that the change was instigated after consultation with fighter pilots showed a desire to return to the old system because it allowed the quick identification of “friendly” aircraft flying above. Such a change would benefit the “Big-Wing” tactics favoured by Sholto Douglas and Trafford Leigh-Mallory, where a force of Hurricane squadrons had squadrons of Spitfires flying above them. However, one source (ID Huntley, see sources below) advanced another view; he said that an anticipated move into low-level offensive operations by Fighter Command would have meant an intense period of low-level flying training over the UK. Such training would have entailed a risk of friendly-fire incidents and the return of the black port wing was meant as an identification feature to prevent such incidents. Yet another suggestion is that the change was prompted by the bombing of the Cunliffe-Owen aircraft factory near Southampton on the11th of September 1940. The destruction of the factory was caused by a formation of German Bf109 fighter-bombers that approached with their wheels down, looking like they were friendly fighters going to land at the factory airfield. The failure to correctly identify the enemy aircraft obviously resulted in calls for a better means of identification. The changes to colour schemes at command level were again formalised by an Air Ministry Order issued on the 12th of December 1940 (AMO A926/40). It is interesting to see that the order used the terms "duck-egg blue" and "sky" interchangeably to mean the same colour.

The winter of 1940/41 saw the formation of dedicated night fighter squadrons equipped with Blenheims, Defiants, Havocs and the new Bristol Beaufighter. These adopted an all-over finish of black "night" paint with low-visibility "B" type roundels on fuselage sides and upper wings, but usually, roundels were not carried under the wings.

Fighter Command went increasingly over to offensive operations during the early months of 1941. Then on the 7th of April 1941, another order went out that specified the deletion of the black colour on the port wing, reverting to all under surfaces being “sky”, this time with underwing roundels. It was also specified that an 18-inch band of “sky” be painted around the fuselage in front of the tailplane and that propeller spinners should also be “sky”. This time a definitive date was specified as to when all aircraft should have been repainted to this standard. Initially, this was to be by dawn on the 15th of April 1941, but the date was subsequently amended to be a week later on April 22nd. Just why there should have been this abrupt changeover is a bit of a mystery. Again, ID Huntley comes up with an explanation; he says that there had been suspected incidents of German “tip-and-run” raids on southern England by German fighter-bombers painted with one underwing black to confuse the AA defences. Therefore the switch back to all “Sky” under surfaces was to try to catch out such raiders (there seem to be no official documents that support this claim). Black port underwings did return for use in exercises to identify between “friendly” and “enemy”. One example is the major six-day anti-invasion exercise that was run from 30th June 1941.

A Tomahawk taking part in exercises during the summer of 1941, sporting a partly black painted underside to its port wing.

Hurricane with "sky" underside and type "A" underwing roundels. Notice how one wing can be thrown into shade by the angle of the sun, making it appear darker.

In August 1941 Fighter Command switched the underside colour of its fighters from “sky” to “medium sea grey”. The band of "sky" around the rear fuselage remaind. At about this time yellow stripes were added to wing leading edges to help identify friendly fighters approaching from behind. This was part of a change of camouflage colours better suited to cross-channel operations with the brown and green top camouflage pattern being changed to one of grey and green. Apparently, the Tomahawk fighters of Army Cooperation Command retained “sky” undersides until July of 1942. At first the type "A" underwing roundels were retained on undersides, but the following year (July 1942) type "C" roundels with a thinner circle of white were introduced.

The progression of Hurricane underside colour schemes in Northern Europe from 1938 until1944 (gif animation). Only a few Hurricanes remained in front-line operations in Europe on D-Day.

Clipped-wing Spitfire with medium sea grey undersides, "sky" band around the rear fuselage, "sky" propeller spinner, yellow leading edges to the wings and the type "C" roundels with reduced area of white introduced in July 1942.

The Black and White stripes known as “D-Day" or "invasion" stripes were applied to both British and American aircraft flying in daylight over Europe as part of the D-Day operations and until the end of the war. However, black and white stripes had been used on Typhoon fighters as early as December 1942 to make them easier to distinguish from German FW190s. Other identification schemes used were yellow chordwise bands on both Typhoons and Army Cooperation Command Mustangs. Operation “Starkey”, a deception plan to fool the Germans into thinking a major invasion of Northern France was to occur in September 1943, also involved painting many aircraft with white, or black and white, stripes on their wings. The black-and-white stripes for "Starkey" had been painted over the wing roundels, covering them up, whereas the D-Day stripes were painted further inboard, leaving the wing roundels visible. The Operation Starkey scheme did not have any stripes on the fuselage.

Bristol Beaufighter sporting "invasion" stripes.

Above: Spitfire Mark IX with black and white "D-Day Stripes". It sports non-standard size and font for the Squadron codes and has the Free French Cross of Lorraine ☨ insignia near the cockpit.

Above: Spitfire Mark IX with black and white "D-Day Stripes". It sports non-standard size and font for the Squadron codes and has the Free French Cross of Lorraine ☨ insignia near the cockpit.

The aircraft of the Royal Navy also mirrored the changes in under-surface markings during the early war years. The Blackburn Skua and Rocs and Fairey Fulmars did not come directly under Fighter Command control, they lacked the necessary radio equipment to be guided to interception. However, when alerted to incoming German raids such aircraft would often be “scrambled” to patrol over their own airfields. When it was found that Fighter Command had no provision for defending the fleet anchorage at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands (the Navy had confidently expected it could defend itself with AA fire alone), an airfield at Hatston was quickly built and Navy Skuas and Rocs allocated for the defence of the anchorage. Thus Skuas and Rocs had their port wings painted black and starboard wings painted white, just like RAF fighters. Photos show that some Skuas seem to have been painted with gloss black paint rather than the regulation "night", presumably because it was unavailable to the Navy at the time. The Blackburn Skuas that went to the South Atlantic aboard HMS Ark Royal in the search for the German raider Graf Spee had black and white undersides to their wings while still sporting their all-silver pre-war finish on top.

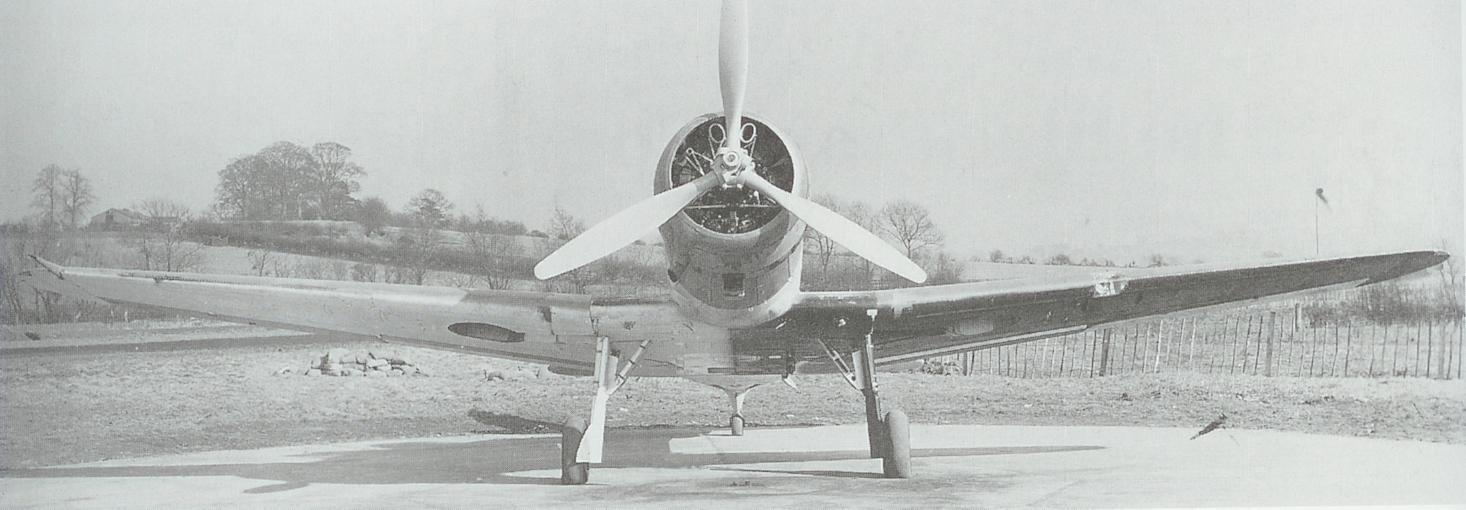

Front view of a Blackburn Roc, showing the black and white undersides of the wings.

This picture of a Skua (L3012 "K") being recovered from the sea off Bermuda reveals some interesting points - Note how the undercarriage and flap recess on the port side are painted black - This shows that at one stage the underside of the port wing was painted black. Also, it is just possible to make out the outline of a roundel on the port wing, showing through the overpainted light underside paint. For the story behind the picture see "The Myth of Black Sunday".

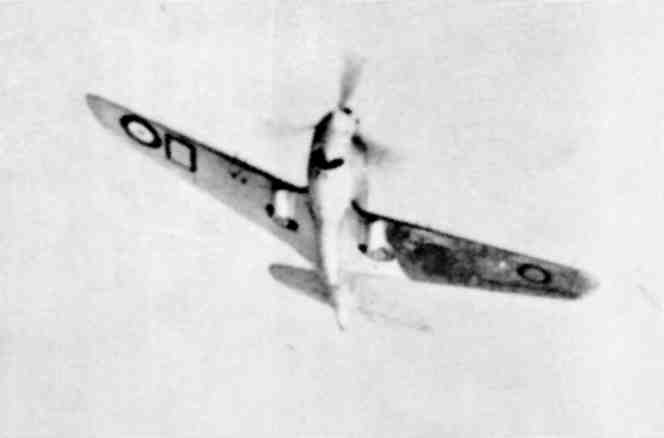

However, with one wing painted black, from below the long-nosed Skuas and Rocs had a passing resemblance to the German Henschel Hs126 parasol observation aircraft. The RAFs response to the first German bombing raid on Britain, on the 16th October 1939 against shipping off the Rosyth naval base, was disrupted by reports of Henschel Hs126 aircraft in the area. This turned out to be Blackburn Rocs flying from the nearby Donibristle airfield.

The single black wing could make an aircraft appear like a parasol design when viewed under certain light conditions. That seems to have happened on the 16th October 1939, when Blackburn Rocs were reported as Henschel Hs126 observation aircraft.

The switch to “sky” undersurfaces was also done by the Navy, painting the undersides of Skuas and Rocs with locally-mixed paint while retaining the sides of the aircraft in the standard Navy “light-grey” colour. The Skua retrieved from Trondheim harbour in 2011 had such a scheme.

NOTES

¹ The first British radar set capable of tracking an aircraft over land was the experimental AMES Type 8, the first of which became operational in late 1940. Developed into the production AMES Type 7 (the lower number is correct), they were mostly used for guiding the interception of enemy bombers by night, known as Ground-Controlled Interception (GCI). The Observer Corp was still essential for tracking raids in daylight, particularly those at low-level under radar coverage. Renamed the Royal Observer Corp in 1941, the organisation stood down in May of 1945 and took on a different role during the Cold War.

LINKS

Simple overview of Supermarine Spitfire camouflage and markings.

Skua and Roc colour schemes and markings.

Simple overview of Supermarine Spitfire camouflage and markings.

Skua and Roc colour schemes and markings.

SOURCES

Air Ministry Orders A154/39, A298/39, A926/40: These and later orders were reproduced in the book "British Aviation Colours of World War Two" edited by John Tanner, published by Arms and Armour Press in 1976 as part of a series for the RAF Museum at Hendon. The book contained a colour chart of the colours used by the RAF based on samples used by the Ministry of Aircraft Production. The same sort of chart can be found on page XXIII in Volume V of "Aircraft of the Fighting Powers" published in 1944.

“Port underwing, Night, Phase III”: an article by ID Huntley in the August 1970 edition of Aircraft Illustrated magazine.

“Aileron overspray problems, 1937-1939”: An article by ID Huntley in the October 1970 edition of Aircraft Illustrated magazine. A letter in the same magazine from James Goulding adds some interesting comments to Huntley’s earlier article in the August edition.

“Fighting Colours – RAF Fighter Camouflage and Markings 1937-1969”: By Michael JF Bowyer, published by Patrick Stephens Limited in 1969. ISBN: 85059 041 8.

“Aircraft Camouflage and Markings 1907-1954”: By Bruce Robertson, published by Harleyford (Harborough) Publications in 1954.

The various “Camouflage and Markings - RAF Northern Europe 1936-45” magazine style “bookazines” published by Ducimus books in the 1960s that covered different RAF aircraft. There is obviously a lot of overlapping information across the different titles. The one on “Hawker Hurricanes in Northern Europe 1936-45” (No 3 in the series) by James Goulding covers the subject well, while "Bristol Blenheim in Northern Europe 1936-45" (No 7 in the series) covers the reason for the black starboard aileron on some Blenheim fighters.

“Birth of the Few”: By Henry Bucton, ISBN 1 85310 972X. It details the events of 16th October 1939, including the misidentification of Rocs as Hs126s.