Dinger's Aviation Pages

De Havilland DH93 Don

Why was this advanced design rejected?

Article revised June 2025.

The de Havilland Don prototype "E3" as originally built, with a dummy turret. It should also be noted that the dark colour of the aircraft is due to the use of orthochrome film, it was actually bright yellow.

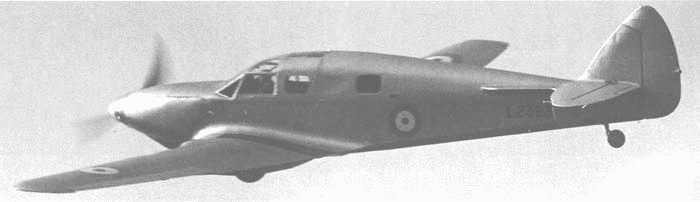

The Don prototype at the Hendon Airshow in June 1937, only 8 days after it had first flown. This time photographed with "normal" film. It is wearing the "new types" number 1 to identify it to the public from a list printed in the official programme. It is still in its original configuration with a dummy turret and prior to the fitting of finlets. Notice the trailing step to give access onto the wing. However getting onto the wing was still difficult, even with this aid.

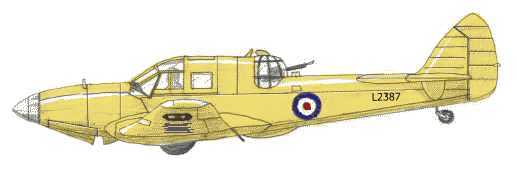

The Don prototype when fitted with a working turret. At this stage, it has not yet acquired the finlets under the tailplane and it still has a large area of horn balance on the rudder. It is carrying its "B" class registration number of "E-3". An extremely "clean" aircraft, the air-cooled Gypsy XII did not need a radiator. The wheels protruded a little when retracted, which would have helped to reduce damage in the event of a wheels-up crash-landing. Note the small "bump" under the fuselage, a feature of the turret-equipped aircraft, this was associated with a prone bomb-aimers position. Again, the use of orthochrome film renders the yellow areas dark.

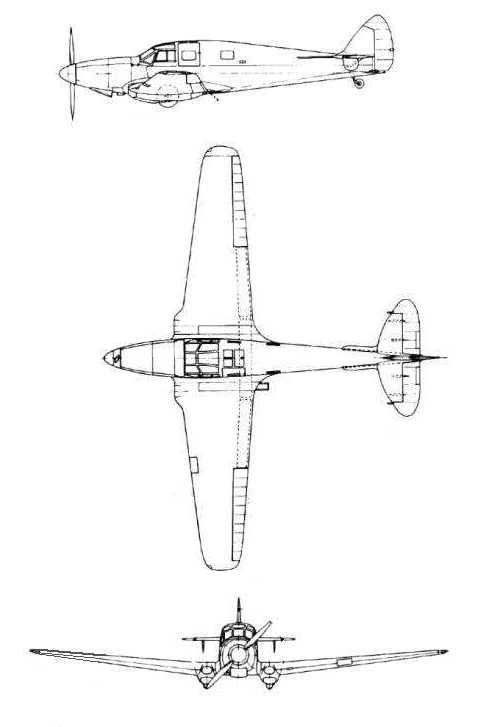

Designed to Air Ministry specification T6/36 the beautiful looking DH93 Don was an all-in-one training workhorse. A student pilot and instructor sat side-by-side up front, while behind in the cabin was accommodation for a trainee WT (radio) operator and behind that a hand-cranked turret for a trainee air gunner with a Lewis gun. In the wing was a machine gun so that the student pilot could get in some air gunnery training, and there were racks for 16 practice bombs (little 2-pounders) and a hatch in the floor for a bomb sight to allow a trainee bomb aimer to practice his art. Power was provided by de Havilland's air-cooled Gypsy XII ¹ engine of 425 hp (the air was taken in by two inlets at the root of the wings and directed over the engine from the rear). With a retracting undercarriage and constant-speed, variable-pitch propeller, the Don was very state-of-the-art when the prototype took to the air on the 18th June 1937. Amazingly, it was flown at the annual Hendon Airshow only 8 days later. The Don was named after the title used by British university professors, clearly reflecting its role as a trainer. Its wooden construction was based on the practices pioneered in the DH 88 Comet racer and DH 91 Albatross airliner, construction methods brought to perfection in the DH98 Mosquito. The Air Ministry ordered 250 examples of the Don even before the prototype flew.

Another view of the prototype Don.

The original T6/36 specification had called for a three-seat aircraft, with side-by-side seating for a student pilot and instructor and a dorsal turret for a trainee air gunner. It was anticipated that if a student pilot was not carried, then an air-gunnery instructor could be accommodated instead. The operational requirement that the specification was meant to address (OR34) was for a replacement for the Hawker Hart and Hinds that were being used for advanced pilot and air gunner training at the time. The Hart and Hind trainers were a valuable asset for the RAF, providing advanced pilot training, including aerial gunnery practice with the single forward machine gun, if fitted with dual controls. They could also be used for rear gunner, bomb aimer or radio training if fitted with the appropriate equipment in the rear cockpit. A top speed of over 200 mph (322 kph) was specified for their replacement, along with a ceiling of not less than 20,000 feet (6096 metres) and the ability to land within 500 yards (457 metres). Given its use as a pilot trainer, good control and stalling characteristics were stressed as being essential. However, the Air Ministry then went on to issue amendments to the specification to expand the equipment to be carried. The weight of the additional equipment required for these roles is usually blamed for the failure of the Don.² But was that really the case? The original specification was issued on the 12th of June of 1937 with the amendments issued only a month later (25th July). Surely a gap of only one month would not have mattered in the design process? There was another set of amendments issued, but that wasn't until the 24th of June 1938, a full year after the Don prototype had flown, and these were to do with its reconfiguration to carry passengers. It is unlikely that the Don would have been expected to fly with all the equipment for the various roles installed at the same time. The radio equipment would have been removed for air-gunnery and bomb-aiming training and the armament would have been removed for the radio training role.

The Don prototype L2387 in later configuration with finlets under the tailplane that were added after initial testing and used on all subsequent production aircraft. Also, note that the area of horn balance on the rudder has been reduced. There are small practice bombs under the wing. The bomb aimer's "bump" under the fuselage is more pronounced in this view.

Initial testing of Don L2387, at the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Martlesham Heath from September 1937, showed up unsatisfactory stalling characteristics and heavy controls, both highly undesirable in a training aircraft. De Havilland improved its handling with the addition of strips along the leading edge of the wing towards the wingtips the addition of small finlets under the tailplane and reducing the horn balance area of the rudder. The Don already had anti-spin strakes in front of the tailplane (like those used on the de Havilland Chipmunk a decade later). Various other modifications were carried out to try to improve control, but the Don was still criticised for the poor view from the cockpit, an excessive takeoff run and heavy elevator control. The climb rate of the Don was particularly disappointing, being on a par with a Tiger Moth biplane, and greatly inferior to the Hart and Hind trainers it was meant to replace. Testing continued until April 1938; apparently a three-bladed propeller was tested, which improved the takeoff performance but full engine power was required to maintain an adequate rate of climb so it was not adopted for production aircraft. The Don had been designed by Arthur Hagg, de Havilland's chief designer, but he had left the company around the time of the Don's first flight following disagreements with the company chairman, Alan Butler. This meant that the task of sorting out the Don's issues fell on the shoulders of Hagg's replacement, Ronald Bishop, who would go on to find fame as the designer of the famous de Havilland Mosquito.

The Don Turret in close-up. The manual turret was designed by Armstrong Whitworth and very similar to the one used on the Avro Anson and very early Whitleys. The small fin on top of the turret counteracted the drag of the gun barrel to make the turret easier to move around. The purpose of the "box" to the rear of the turret is unknown, one suggestion is that it contained a small emergency anti-spin parachute, a device often fitted to aircraft under evaluation at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE). Note that a direction-finding (DF) radio loop is mounted on the top of the cabin. This seems to be the only photo to show a DF loop in place on a Don and may be an example of the extra equipment that the Air Ministry asked to be fitted. By the late 1930s, experience of using a DF loop would be essential for the training of radio operators. The Percival Proctor that took over the radio training role had a smaller DF loop mounted inside a perspex blister.

Visible under the port wing are 8 small practice bombs, the same amount could be carried under the starboard wing, giving a total of 16. Also visible is the opening for the machine gun in the leading edge of the port wing.

The design had coalesced around the concept that just one type of training aircraft could meet the bulk of the needs of training the whole range of aircrew; pilots, observers (navigator/bomb aimers), radio operators and air gunners, with the Airspeed Oxford complimenting it in smaller numbers to finish off the training of pilots for multi-engined aircraft. However, it quickly became apparent that large numbers of multi-engined trainers would be needed to train the pilots of the many multi-engined bombers ordered into production for the RAF expansion, and that these multi-engined trainers would be better "flying classrooms" than the cramped DH93. It was also evident that a trainer with higher performance would be required to prepare pilots for the new Hurricane and Spitfire fighters recently ordered into production. So with the myriad problems being encountered by the Don, the Air Ministry cancelled it and instead ordered more examples of the Avro Anson (which had started as a small airliner adapted for coastal patrol aircraft) for use as a trainer and increased orders for the Airspeed Oxford (23/36). Also the Miles Master³ (16/38) was ordered as a trainer for fighter pilots (later augmented by the Harvard from the USA) and the smaller and lower-performance single-engined Percival Proctor (26/38) was obtained specifically for training WT operators. Somewhat ironically, the Miles Master used reconditioned and upgraded Rolls Royce Kestrel engines, largely taken from the Hart and Hind trainers that the original T6/36 specification had been designed to replace. After war with Germany started, and deliveries of Oxfords and Ansons struggled to keep up with demand, the Air Ministry ordered Caproni Ca311 and Ca313 twin-engined trainers from Italy (specification 2/40). This order was of course cancelled when the Italians joined the war.

The second Don built, L2388. It has a blanked-off, dummy turret.

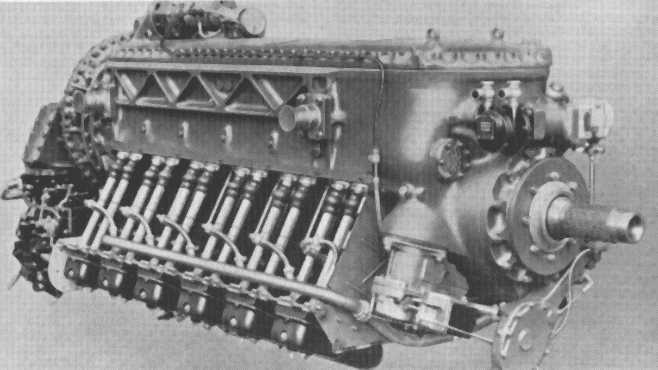

One strong possibility is that the Gypsy XII engine never developed the full power expected of it. Contemporary descriptions of the Gypsy XII engine list it as rated as 525 horsepower, yet modern ones (including the authoritative Lumsden's "British Piston Engines and their Aircraft") list it as only 425 horsepower. If the Gypsy XII was expected to produce 525 hp but only produced 425 hp that would certainly explain a lack of performance. Another disappointing aspect of the Gypsy XII engine was its weight; it had a "dry" weight of 1,058 lb (480 kg). This compared very unfavourably with other aero-engines of the time, for example, the Bristol Mercury 30 had a dry weight of 1,065 lbs (483 kg) but could produce 810 horsepower, nearly double that of the Gypsy XII. The Rolls Royce Kestrel XXX had a dry weight of only 990 lb (449 kg), yet it could produce 720 horsepower. The Gypsy XII was also reported to be a very expensive engine to buy; it cost four times more than the reconditioned Kestrel XXX engines used on the Miles Master trainers. The Gypsy XII could only be run at its maximum power for two minutes or it would risk overheating. Prolonged taxiing could also overheat the engine. The Don did not reach the top speed of 200 mph (322 kph) originally specified in T6/36, having a top speed of 189 mph (304 kph). That was only 4 mph faster than the Hawker Hart and Hind aircraft it was supposed to replace.

The 12-cylinder, supercharged, de Havilland Gypsy XII engine (called the "Gypsy King" in RAF service). It used the standard pistons and cylinders of the earlier Gypsy Major and Gypsy Six (Queen) engines. It weighed considerably more than other aero-engines in the same class while producing much less power. It was also prohibitively expensive (although costs would have gone down if it had gone into more large-scale production).

According to the Air-Britain Specification File (see sources listed below), the T6/36 specification actually specified the Gypsy XII engine and the use of a variable-pitch propeller. There would be a certain logic to this at the time. Engine production was proving to be a bottleneck in the planned expansion of the RAF, with the Rolls Royce Merlin engine, the AW Tiger and the new Bristol sleeve-valve engines having development problems. It would have made sense to try to make use of de Havilland's engines in the expansion programme, and the Gypsy XII was their highest-powered engine and the only one with enough power for advanced military applications. However, the other two companies that prepared designs for T6/36, Avro and Miles, both ignored this requirement and chose to use the Rolls Royce Kestrel engine instead. Perhaps they anticipated that the poor power-to-weight ratio of the Gypsy XII would render it unsuitable for the role.

But surely another major factor in the Don's cancellation was a realisation by the Air Ministry that one type of aircraft was never going to meet all its training requirements. In the late 1930s, the priorities for aircrew training changed considerably. The need for longer and better training in the skills of navigation becoming particularly evident (read C.G. Jefford's book "Observers and Navigators" or this short article from the old "Tee Emm" magazine for details of the big changes in the roles and training of navigators in this period), and the extra room in twin-engined aircraft such as the Anson and Oxford had many advantages for such training.

But surely another major factor in the Don's cancellation was a realisation by the Air Ministry that one type of aircraft was never going to meet all its training requirements. In the late 1930s, the priorities for aircrew training changed considerably. The need for longer and better training in the skills of navigation becoming particularly evident (read C.G. Jefford's book "Observers and Navigators" or this short article from the old "Tee Emm" magazine for details of the big changes in the roles and training of navigators in this period), and the extra room in twin-engined aircraft such as the Anson and Oxford had many advantages for such training.

Another view of the prototype, this time in flight. Note the prominent anti-spin strakes in front of the tailplane and the dark lines on the leading edge of the wings where strips had been added to improve the stalling behaviour.

This meant the only role left open to the Don was that of communications aircraft. A requirement for a version of the Don able to carry passengers was formalised in Air Ministry contract 539246/37, issued around the time of the trainer Don's first flight. Don L2391 was built as a passenger aircraft and was evaluated in this role at A&AEE Martlesham Heath. It was found to have some serious shortcomings. The passenger cabin was cramped and it was difficult to get into, with a large drop from the door to the floor inside. Access onto the wing to get to the cabin door was also difficult and it was felt that entry into the Don would be a problem for any less fit or elderly passengers. The front seats were uncomfortable and there was no provision for heating the cabin. The view from the cockpit was still poor for safe taxiing. The takeoff distance was considered too long for the communication role, and the cockpit instrument layout was judged to be poor. Lastly, the rudder bias operation was described as "useless"! So the Don was certainly not an aircraft suitable for ferrying VIPs around. Although three Dons were later listed as being allocated to No 24 Squadron, the Metropolitan Transport Squadron tasked with flying high-ranking officers and politicians about, only one (L2394) seems to have actually served with the squadron, and only for a few months at the end of 1938. Although the Don was meant to carry between four and six passengers in the communications role, it seems that many of those delivered only had a single seat to the rear of the side-by-side pilot's positions. The failure of the Don for the communications role prompted a flurry of "off-the-peg" specifications from the Air Ministry at the end of 1938 to fill the gap. There was 20/38 for the Percival Proctor in its communications form, 21/38 for the Dragon Rapide in its communication form, 24/38 for the Airspeed Envoy light transport aircraft and 25/38 for the Percival P16 Petrel communications aircraft.

The DH98 Don L2393 as it entered into brief service as a communication aircraft with the turret deleted. Putnam's " De Havilland Aircraft Since 1909" lists this Don as being used by No 11 Group Station Flight based at RAF Northolt, while Air-Britain's Aeromilitaria magazine lists it as going to the station flight at RAF Eastchurch and then being used as an instructional airframe at RAF Locking.

The production run for Dons was cut to 50 aircraft, only 30 of which were built to full flying condition. Most were allocated to the communication role at various station flights at RAF airfields around the UK, while others were sent to flying training schools, although they seem to have only been used in the "hack" role rather than as trainers. Single examples also served with No 24 Squadron (L2394), the Electrical and Wireless School at RAF Cranwell (L2407), and A&AEE at Martlesham Heath (L2391). However, none stayed in service for more than a few months and all ended up as ground-based instructional airframes. The 20 airframes not built to flying condition were delivered by road or rail to various RAF technical training and flying training schools. A full list of Don production numbers, serial numbers and brief notes on their use can be found in a table published in the Summer (June) 2013 edition of Air-Britain Aeromilitaria magazine at the end of a short article by Phil Butler. This list is at odds in several respects with the information in Putnam's "De Havilland Aircraft since 1909" by AJ Jackson. The Putnam's list is based on de Havilland's records, while Air-Britain's list is based on RAF records.

DH93 Don L2393 in flight.

Just how many Dons were built with turrets in the trainer configuration is unclear. It would seem likely that the first four (L2387, L2388, L2389 and L2390) were probably initially built with turrets as trainers. Then L2391 was the first built from scratch as a communication aircraft, after which at least two of the trainers (L2389 and L2390) had their turrets removed and converted to the communication form (photos of them in this layout exist). It is not known if L2387 or L2388 were ever converted.

.

Another view of a Don in "communications" form. The RAF, Royal Navy and Air Transport Auxiliary had a desperate need for aircraft in this class to ferry staff and equipment around. Various civil types were impressed to fill this gap. The ventral bump associated with a bomb aiming position was missing from Dons with the communication layout. The long nose and sharply raked back windscreen gave a poor view for taxiing and takeoff. It is possible that this Don (L2390) was originally built with a turret in trainer configuration and later converted to the communications variant. Putnams has this Don serving at the Central Flying School at Upavon, while Air-Britain lists it as going to the station flight at RAF Grantham (Spitalgate).

Another view of a Don in passenger carrying configuration. In the background, you can see men digging a slit trench in preparation for the coming war. This particular Don (L2392) is listed as being delivered to RAF Eastchurch by both Putnams and Air-Britain.

Only one Don was ever lost in a crash, that was Don L2391 on the 22nd of September 1938 during a fuel consumption test at A&AEE. Its engine stopped responding to the throttle when the control linkage broke and a cross-wind landing had to be attempted; the aircraft stalled a few feet above the ground and the undercarriage collapsed, no one was seriously hurt.

The wreck of Don L2391 after its crash at Martlesham Heath in September 1938. Amazingly, the pilot escaped with only minor injuries.

De Havilland was not as dependent on RAF orders as other British aircraft companies, preferring to build up their position in the civil aviation marketplace, a policy that had been a resounding success, by the mid-1930s they were the most profitable British aviation company. With them setting up a production line for 250 Don aircraft and then seeing the order reduced to only 50 you can see one drawback of doing government work! However, de Havilland was rewarded with extra orders for Tiger Moth trainers and was even asked to build some of the Oxford trainers to be used in place of the Dons. Furthermore, the DH Dragon Rapide small airliner was retained in production (renamed the Dominie) to be used as flying classrooms to train navigators and radio operators. They also benefited from the orders for Percival Proctors and Petrels, since they used the 6-cylinder de Havilland Gypsy Queen engine. Oxfords were produced at the de Havilland factory at Hatfield alongside Dominies and Queen Bee target drones until the Mosquito was ordered, when the Dominie line went to Loughborough the Oxford line was closed down.⁴

This photo appeared in the British aeronautical press in March 1940 showing a Don in use as an instructional airframe at No 2 School of Technical Training (RAF Cosford). Only some 33 months after the first flight of the prototype Don. The trainees would have found the experience of working on the Don of great benefit if they later worked on the DH Mosquito, which used the same construction techniques. Five engineless Don airframes are listed as having been delivered to RAF Cosford, registration numbers L2431 to L2436. Another two built with engines (L2396 and L2398) also ended up at Cosford.

All the published sources I can find indicate that, by the start of WW II, there were no Dons left flying with the RAF. They had all been relegated to instructional airframes (it was the availability of the Gypsy XII engines stripped from them which allowed the small fleet of DH91 Albatross airliners, to be kept flying until 1943). However Janic Geelen, the author of "Magnificent Enterprise - Moths Majors and Minors" suggest that de Havilland may have retained one Don for use for communications and testing duties into the early war years. A table of aircraft histories in Putnam's "De Havilland Aircraft since 1909" lists Don L2412 as still being flown in October 1940 as "E-0232" which suggests it was indeed being used for some testing purpose (de Havilland gave their prototypes and testing machines B-class "E" numbers as in the photo of "E3" at the top of this page). Apparently, a Don was used to test a de Havilland-designed propeller with reverse-pitch that could act as an airbrake, perhaps that was L2412⁵. Bill Gunston, the prolific aviation author, said he encountered a Don at de Havilland's airfield at Hatfield when he visited there as an Air Cadet in 1942 and was allowed to get inside to have a look around, he noted that even the pilot's position seemed cramped. Gunston also said he talked to a pilot who had just flown one into the RAF airfield at Halton; he reports the pilot as saying the Don was "Not a patch on the Proctor".⁶ The Don is also listed as amongst the aircraft flown by the famous test-pilot Eric "Winkle" Brown. All of this implies that at least one Don was kept flying well into the Second World War.

An intriguing image of Don L2412, perhaps the last Don to fly. This may show it when it was in the care of 1927 Squadron of the Air Training Corp at Petersfield.

Another intriguing photo of one of the turret-equipped Dons. The underneath of one wing looks to be painted black, like RAF single-seat fighters in the first year of the war. The upper surfaces and fuselage look like they could be in camouflage colours.

Another intriguing photo of one of the turret-equipped Dons. The underneath of one wing looks to be painted black, like RAF single-seat fighters in the first year of the war. The upper surfaces and fuselage look like they could be in camouflage colours.

A photo published in the September 2013 edition of Air Britain's "Aeromilitaria" magazine showed a Don fuselage (minus engine) being used as a children's climbing frame at the April 22nd 1947 "open day" at the Walsall (Aldridge) airfield, perhaps the last surviving Don airframe, it was probably an old instructional airframe from either the nearby RAF Hednesford or RAF Cosford.

Performance

Max Speed: 189 mph (304 kph). Speed was virtually identical to the Avro Anson and 20mph (32 kph) faster than the Airspeed Oxford. However, it was only 4 mph faster than the Hawker Hind and Hart trainers it was meant to replace.

Range: About 900 miles (1,448 km). Quite good for a training aircraft of this vintage and surprisingly superior to both the twin-engined Anson and Oxford.

Ceiling: 23,300 ft (7,102 metres). More than enough for its intended role and considerably higher than either the Anson or Oxford.

Climb Rate: A disappointing 820 feet per minute, about the same as a Tiger Moth! Greatly inferior to the Hawker Hart and Hind trainers it was meant to replace.

Armament: Provision for a Browning machine gun in the port wing (although the prototype seems to have been fitted with a Vickers) and a Lewis or Vickers K gun in the rear turret (where fitted). Upto 16 practice bombs (8 under each wing).

Dimensions

Length: 37 feet 4 inches (11.38 metres).

Wingspan: 47 feet 6 inches (14.48 metres).

Weight with turret and equipment in trainer mode: 6,860 lb (3,112 kg).

Empty weight in communication form: 5,050 lb (2,290 kg).

Loaded weight in communication form: 6,530 lb (2, 962 kg).

DH 93 Don, Note how similar the tailplane is to the famous DH88 Comet racer.

Conclusion

There is no simple answer to why the Don was a failure. The Air Ministry changes to the specification might have had a negative effect on performance, although it could be just an excuse by de Havilland to explain away the Don's failure. The poor power-to-weight ratio of the Gypsy XII engine certainly seems to be contributory factor. The change in doctrine for the training requirements of the RAF surely had a bearing on the Don's rejection. But above all, it seems that the Don had handling characteristics that were just unacceptable for a training aircraft and it was simply not fit to serve in the communication role.

A Hawker Hind, the trainer version of which the DH93 Don was designed to replace. The Don was only 4 mph faster and had a much slower rate of climb.

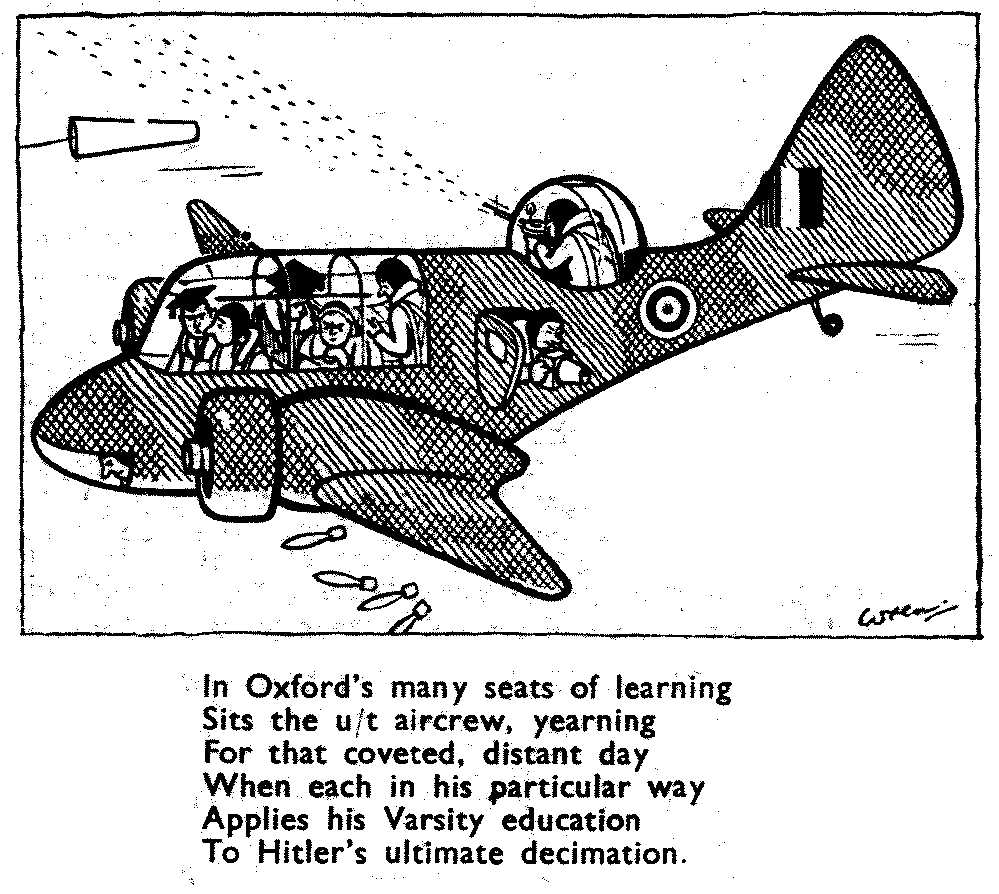

While the "all-in-one" trainer concept didn't come to fruition in the DH Don, it bore fruit in the twin-engined Airspeed Oxford (as seen in the above "Oddentification" cartoon by "Wren") and Avro Anson.

What If ?

What If ?

Above: I've painted these Dons as if they had entered service in their original role. In this case in the markings of No 1 Air Observers School at Desford around 1939 (they actually used Avro Ansons). If the Don had entered large-scale production, would de Havilland have been satisfied they were "doing their bit" and never gone on to develop the outstanding DH 98 Mosquito? Considering the poor flying qualities of the Don, it's probably just as well it never saw widespread use.

If the idea behind the T6/36 Specification had been to try to find a way to make use of de Havilland engines in the expansion of the RAF, then maybe a better plan would have been to support the development of the Reid and Sigrist RS1 "Snargasher" and its RS2 development. The RS1 used two de Havilland Gypsy Six engines. The Don's Gypsy XII engine was essentially two Gypsy Six cylinder blocks joined to a common crankshaft with a supercharger. The RS1 was a two or three-seat crew trainer that could exceed the 200 mph called for in the T6/36 specification. Of course, the Gypsy Six (called the Gypsy Queen in RAF service) was also used in the de Havilland Dominie, Percival Proctor and Petrel that went some way to fill the gap for crew trainers and communication aircraft caused by the Don's cancellation.

If the idea behind the T6/36 Specification had been to try to find a way to make use of de Havilland engines in the expansion of the RAF, then maybe a better plan would have been to support the development of the Reid and Sigrist RS1 "Snargasher" and its RS2 development. The RS1 used two de Havilland Gypsy Six engines. The Don's Gypsy XII engine was essentially two Gypsy Six cylinder blocks joined to a common crankshaft with a supercharger. The RS1 was a two or three-seat crew trainer that could exceed the 200 mph called for in the T6/36 specification. Of course, the Gypsy Six (called the Gypsy Queen in RAF service) was also used in the de Havilland Dominie, Percival Proctor and Petrel that went some way to fill the gap for crew trainers and communication aircraft caused by the Don's cancellation.

Notes

¹ The Gypsy XII was later renamed Gypsy King I when used by the RAF. Just how many were produced is open to debate. The de Havilland Museum has an information board saying only 50 engines were built, while Lumsden (see sources below) says about 90. The low figure would seem improbable since 30 Dons were built with engines along with 7 Albatross airlines (which used four engines each) making a total of 58 engines needed to power the aircraft known to have been delivered.

² Examples of books that blame an increase in weight for the Don's rejection: "Industry and Air Power, The Expansion of British Aircraft Production, 1935-1941" by Sebastian Ritchie, Chapter 3,(page 106). Also, Putnam's "De Havilland Aircraft Since 1909" by A.J. Jackson. This narrative has gone on to be included in the Wikipedia page on the DH93 Don.

³ It is worth noting that the Miles Master started life as the Miles M9 Kestrel project which was itself tendered to the same specification as the DH93 (Air Ministry Spec T6/36). Avro had also schemed two designs for the specification; the Type 676 and Type 677. It may be that one of the Avro designs was designed for the pilot-training role while the other had a turret for the air-gunnery role.

⁴ Thanks to Janic Geelen for putting me right on the way de Havilland moved production around to cope with the demands of the war - see his book "Magnificent Enterprise - Moths Majors and Minors".

⁵ The listing of Don L2412 in the Aeromilitaria Summer 2013 magazine shows it being allocated to the Royal Aircraft Establishment and eventually being given to 1927 Squadron of the Air Training Corp at Petersfield with the "ground instruction" serial number 3356M, but no dates are given.

⁶ Quoted in Gunston's book "Back to the Drawing Board" - see sources below.

² Examples of books that blame an increase in weight for the Don's rejection: "Industry and Air Power, The Expansion of British Aircraft Production, 1935-1941" by Sebastian Ritchie, Chapter 3,(page 106). Also, Putnam's "De Havilland Aircraft Since 1909" by A.J. Jackson. This narrative has gone on to be included in the Wikipedia page on the DH93 Don.

³ It is worth noting that the Miles Master started life as the Miles M9 Kestrel project which was itself tendered to the same specification as the DH93 (Air Ministry Spec T6/36). Avro had also schemed two designs for the specification; the Type 676 and Type 677. It may be that one of the Avro designs was designed for the pilot-training role while the other had a turret for the air-gunnery role.

⁴ Thanks to Janic Geelen for putting me right on the way de Havilland moved production around to cope with the demands of the war - see his book "Magnificent Enterprise - Moths Majors and Minors".

⁵ The listing of Don L2412 in the Aeromilitaria Summer 2013 magazine shows it being allocated to the Royal Aircraft Establishment and eventually being given to 1927 Squadron of the Air Training Corp at Petersfield with the "ground instruction" serial number 3356M, but no dates are given.

⁶ Quoted in Gunston's book "Back to the Drawing Board" - see sources below.

Sources

"Out-moded Teacher - De Havilland's Don Crew Trainer": An article by Daniel Ford in Air Enthusiast magazine edition 105 May/June 2003

"The British Aircraft Specification File": by KJ Meekoms and EB Morgan, an Air-Britain publication. ISBN 0 85130 220 3.

"The Discarded Don": a two-page article in the Winter 2000 (issue 104) of Air Britain Aeromilitaria magazine. Unattributed, probably by the magazine's editors; James Halley and Ray Sturivant.

"The de Havilland Don": a 3-page article by Phil Butler in the Summer (June) 2013 edition (no 154) of Air Britain "Aeromilitaria" magazine.

"DH - A History of de Havilland": by C. Martin Sharp mentions the Don being used to test reverse pitch propellers. Airlife ISBN 0 906393 20 5.

"De Havilland Aircraft since 1909": by AJ Jackson, Putnam ISBN 0 370 30022 X (2nd Edition).

"Back To The Drawing Board - Aircraft That Flew But Never Took Off": by Bill Gunston, published by Airlife in 1996. ISBN 1 85310 758 1.

"Armament of British Aircraft - 1909 -1939": By H.F. King, published by Putnam in 1971. ISBN: 0 370 00057 9. The author flew in the prototype Don, noting the aircraft had a prone bomb aimer's position and was fitted with a Vickers machine gun in the wing. He also confirms that a Don with a reversible pitch propellor was used in dive bombing trials.

"British Flight Testing - Martlesham Heath 1920-1939": By Tim Mason, first published by Putnam in 1993. ISBN 0 85177857 7. It mentions the use of a three-bladed propeller to try to improve performance.

"British Piston Aero-Engines and Their Aircraft": By Alec Lumsden. First published in 1994 by Airlife Publishing. ISBN 1 85310 294 6.

"The British Aircraft Specification File": by KJ Meekoms and EB Morgan, an Air-Britain publication. ISBN 0 85130 220 3.

"The Discarded Don": a two-page article in the Winter 2000 (issue 104) of Air Britain Aeromilitaria magazine. Unattributed, probably by the magazine's editors; James Halley and Ray Sturivant.

"The de Havilland Don": a 3-page article by Phil Butler in the Summer (June) 2013 edition (no 154) of Air Britain "Aeromilitaria" magazine.

"DH - A History of de Havilland": by C. Martin Sharp mentions the Don being used to test reverse pitch propellers. Airlife ISBN 0 906393 20 5.

"De Havilland Aircraft since 1909": by AJ Jackson, Putnam ISBN 0 370 30022 X (2nd Edition).

"Back To The Drawing Board - Aircraft That Flew But Never Took Off": by Bill Gunston, published by Airlife in 1996. ISBN 1 85310 758 1.

"Armament of British Aircraft - 1909 -1939": By H.F. King, published by Putnam in 1971. ISBN: 0 370 00057 9. The author flew in the prototype Don, noting the aircraft had a prone bomb aimer's position and was fitted with a Vickers machine gun in the wing. He also confirms that a Don with a reversible pitch propellor was used in dive bombing trials.

"British Flight Testing - Martlesham Heath 1920-1939": By Tim Mason, first published by Putnam in 1993. ISBN 0 85177857 7. It mentions the use of a three-bladed propeller to try to improve performance.

"British Piston Aero-Engines and Their Aircraft": By Alec Lumsden. First published in 1994 by Airlife Publishing. ISBN 1 85310 294 6.

Links

Technical information on the Gypsy XII engine (aircraft investigation website).

Report on the crash of L2391 on Aviation Safety Net