Dinger's Aviation Pages

BLACKBURN SKUA

AN INTRODUCTION

Please note this is only one of a number of pages on this website dealing with the Blackburn Skua. To see a full list of them <CLICK HERE>.

The Blackburn Skua was a fighter/dive-bomber/fleet scout used by the British Royal Navy in the early years of World War II. All but forgotten now, the Skua was flown in combat over Norway, the beaches of Dunkirk and in the Mediterranean. During the Norwegian campagn alone Skuas are verified as having destroyed at least 40 enemy aircraft. It gained the distinction of being the first Royal Navy aircraft to shoot down a German aircraft in World War Two (a Dornier Do18 Flying boat on 26th September 1939) and also being the first aircraft to sink a German warship in WW2 when Skuas sank the cruiser Königsberg in Bergen harbour on 10th April 1940. The Skua was also the first aircraft to carry out an interception of an enemy aircraft controlled by shipborne radar.

The Skua was built to Air Ministry Specification O.27/34 issued in 1934. Its designer was George Edward Petty working under the direction of Major Frank Arnold Bumpus. Bumpus was nominal Chief Designer until 1937 although he seems to have given responsibility for all new designs (except flying boats which were the responsibility of Major John Rennie) to Petty from 1929.

On the left is Major Frank Bumpus, on the right is George Petty.

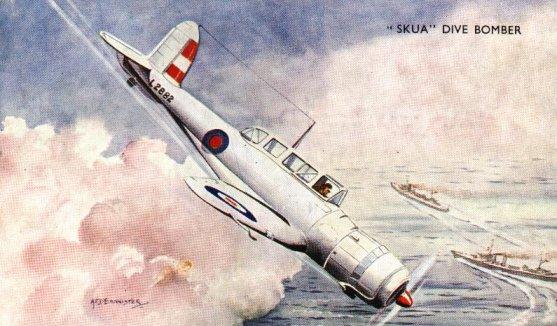

Blackburn Skua in Flight.

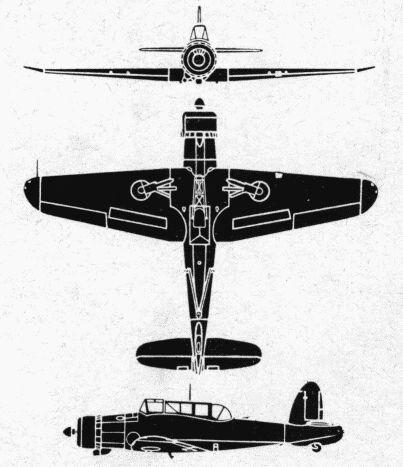

Above is a reproduction of a wartime aircraft spotter recognition card of the Skua. It shows the underside of the aircraft and you can see the "V" arrestor hook frame, the cradle to swing the 500 lb (227 kg) bomb away from the aircraft in a dive-bombing attack, the recess for the bomb itself and the extended "inverted gull" fillets which joined the trailing edge of the wing to the fuselage. A more detailed set of plans for the Skua (in PDF format) can be found at <this link>.

Skua L2883, It was delivered to 800 Squadron in January 1939. It had a busy life, seeing service at Donibristle, Worthy Down, Lee on Solent and then with 771 Squadron in the Orkney Islands. sadly, it flew into a barrage balloon cable at Scapa Flow on the 9th July 1942 with the loss of the two crew.

The initial prototype Skua had problems with stability and it and the second prototype (both known as Skua Mk Is) had to be modified with a longer nose and upturned wing-tips, features carried over to the production aircraft (Skua Mk II). Longitudinal instability at low speeds was still an issue and the landing characteristics of the Skua prototypes were so bad that they were fitted with leading-edge slats and an experimental "spring" device on the elevator for tests to try to find a solution. The elevator spring was adopted on production aircraft as the cure for the problem. During early evaluation of the prototypes, the spin characteristics of the Skua was judged bad enough to prompt the fitting of an anti-spin parachute in the tail of production aircraft, to aid recovery. The long nose adopted on production aircraft meant that the Skua was always liable to "nose-over" if the brakes were applied too violently.

Skua L2933 was delivered to 803 Squadron at Worthy Down in March 1939. It survived in service until April 1944, ending its days with 771 Squadron in the Orkney Islands.

The Skua prototypes used the well-tried Bristol Mercury engine (the Mk IX) but the use of these engines in the huge Blenheim bomber programme meant that production Skuas had to use the new Bristol sleeve-valve Perseus XII engine. Although the Perseus engine was the first sleeve-valve engine to go into mass-production it had a good record of reliability because it was only produced by the main Bristol factory with excellent quality control that rejected any malformed engine sleeves, but with a subsequent slow rate of production. One of the main advantages of the sleeve-valve Perseus was its quietness, meaning less noise for the Skua crew (one pilot described the steady hum of the Perseus as "soporific") and also giving less notice to the enemy of its approach. However, the Perseus offered only a marginal advantage in power over the traditional poppet-valve Mercury engine of the same size and the type only had a relatively small production run before production was switched to the more powerful Taurus and Hercules engines. These later Bristol sleeve-valve engines, particularly the Taurus, went through a stage of very bad reliability when first mass-produced. Problems cured in the supremely reliable later model Hercules and Centaurus.

Above is a contemporary postcard of a painting of a Skua. The markings are probably authentic (the serial number L2882 is). L2882 was delivered to 803 Squadron in January 1939 but was transferred to 800 Squadron later that year. L2882 led 6 Hurricanes from HMS Ark Royal to Malta in November 1940. It served in Malta for a month before flying on to Egypt where it was used by the "pool squadron" at the RNAS airfield at Dekheila, near Alexandria.

When reading histories of the Royal Navy's Air Branch in the Second World War, you often find naval writers blaming the lacklustre performance of the Skua on the RAF and Air Ministry who had nominal control of the Navy's aircraft until 24th April 1939. This is somewhat unfair, because although the Air Ministry issued the operational specifications for new aircraft, the doctrine behind the designs, along with the performance targets and initial specifications for naval aircraft, were drawn up by the Royal Navy itself. Meanwhile, writers in the RAF camp blame the Skua's poor performance on the specifications laid down by the Admiralty, particularly for it having to share the role of fighter and dive bomber. It is interesting to note that both the USA's Dauntless dive bomber and the Japanese Aichi "Val" dive bomber are often praised for their ability to act as fighters in an emergency. The one area that the Air Ministry can perhaps be blamed for is the low priority for production initially allocated for the Skua and its turret-fighter derivative, the Roc. With the growing threat of a full-blown war on the continent of Europe, priority was given to land-based fighters and bombers and production of both the Skua and Roc were delayed.

At the time the Skua was ordered, the Royal Navy had dropped the use of single-seat fighters to defend the fleet. Instead anti-aircraft fire (AA) was deemed to be the best way to defeat hostile air attacks. The Skua was seen as having four roles. Firstly as a dive bomber to damage the flight decks of hostile aircraft carriers to blind the enemy by depriving them of the ability to do scouting and spotting missions. Second, was the "fighter/reconnaissance" role where it would keep contact with a hostile enemy fleet during daylight (the initial finding of the enemy fleet having been done by scouting Fairey Swordfish or Blackburn Shark aircraft). Thirdly, was the role of escort fighter to accompany torpedo bombers in striking the enemy fleet, by taking on or decoying away enemy fighters and suppressing enemy AA fire with bombs and machine gun fire. Lastly was the ability to attack enemy aircraft that were shadowing the fleet outside the range of the anti-aircraft barrage, although the Skua's radio equipment was not suited to this role (it had no speech communication, only morse code) and the Blackburn Roc was developed from the Skua specifically for this task.

In combat however, the Skua was forced to be used as a fighter much more often than as a dive bomber. Off Norway and in the Mediterranean its performance as a fighter was often better than might be imagined just looking at its modest speed in level flight. Its long endurance meant it could loiter at altitude (once it got there, it had a very poor rate of climb) and dive onto its victims.

One aspect of the Skua design that is often misrepresented is its two-seat layout. In numerous books, it is asserted that the second crewman was a navigator whose job it was to keep track of the aircraft's position over the open ocean. In fact, the second crewman was often a Telegraphist - Air Gunner (TAG) who was not trained in navigation at all. On most missions the TAG would not even be in the pre-flight briefing and would have only the haziest idea of where they were flying to! (See the article "Oh Calamity!" for verification). It was the pilot who was responsible for navigation. Having said that, the TAG was essential to the pilot finding his way back to the carrier; the Skua carried an R1110 receiver that picked up radio signals from a Type 72 rotating beacon on the aircraft carrier. This allowed to TAG to work out the bearing of the carrier and thus the Skua could find its way home even if the carrier had to change position because of enemy action. The process was complicated, involving the use of a special accurate clock and stopwatch and could never have been done by the pilot, hence the need for a second crewman.² A navigator (called an Observer in the wartime Royal Navy Air Branch) could be carried on a Skua to find the way to a target or in the "fighter/reconnaissance" role. For example, the formations on the raid on the Königsberg were led by Skuas with an Observer and all three Skuas in the search for the SS Fanad Head had Observers onboard.

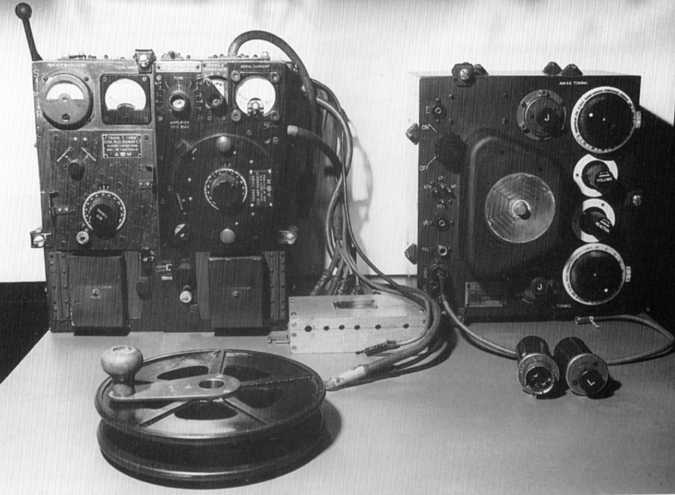

While the Skua's means of finding its way back to the carrier by radio homing was strikingly advanced, other aspects of its radio equipment had serious drawbacks. It carried a T81083 radio transmitter and an R1082 receiver. Because of the Royal Navy's doctrine of keeping radio communication to a minimum (to stop the position of its ships being triangulated by the enemy monitoring their signals), these were usually only used for terse Morse code communication. The sets were perfectly capable of speech communication if fitted with the necessary coils. However, the Royal Navy doctrine of enforced radio silence meant that speech communication was discouraged, to the extent that the official manual for the T1083 transmitter advised that the microphone transformer be shorted out by a piece of wire to disable speech in Fleet Air Arm use (see AP1186 Section 1, chapter 5, paragraph 93). This meant communication between aircraft was limited to hand signals or the signal lamps positioned on top of the cockpit and under the fuselage. This must have severely limited the ability of the Skua crews to cooperate, particularly in the fighter role - No "Tally Ho Red Leader, bandits 9 o'clock low" for the poor Skua pilots!

The communication equipment carried by the Skua: On the left is the T1083 transmitter and on the right is the R1082 receiver. In front, on the left, is a spool used to wind out and in the long trailing aerial that could be used with the equipment. The receiver used different plug-in coils to operate at different frequencies, two of which can be seen on the right. The transmitter had much larger swappable coils that required the whole panel with a knob on the left and the large circular panel on the right to be replaced. While capable of speech communication (R/T), the Royal Navy preferred to only use Morse code (W/T).

There is an excellent article on Royal Navy Air Branch radio equipment at the start of the war on Matt Willis' Naval Air History website at <this link>.

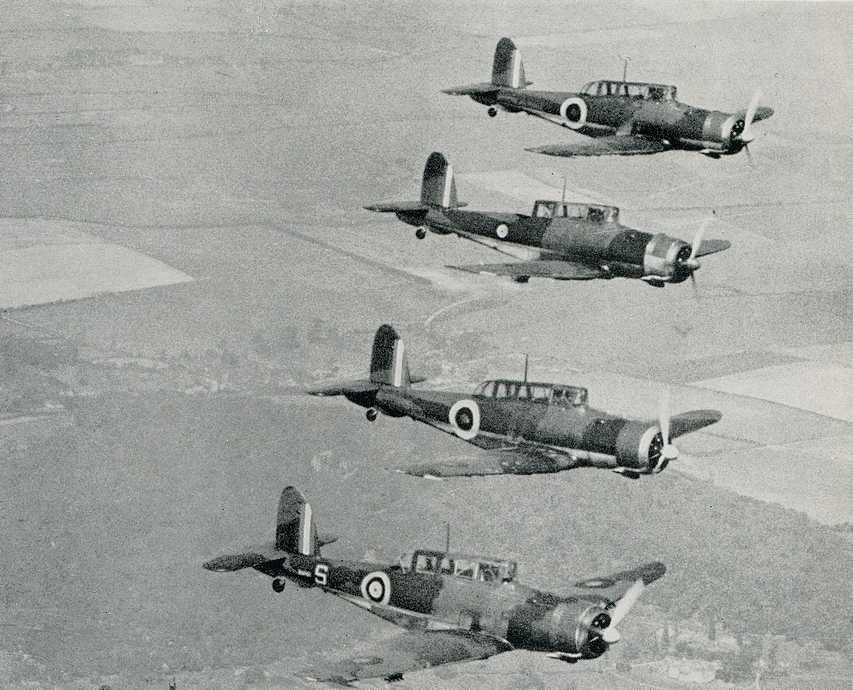

Skuas in formation. Note the different roundel styles.

Two Skua prototypes were ordered in 1935 and the first of these (K5178) did not fly until nearly two years later, on 9th Feb 1937. In October of that year, it went for handling trials at A.&A.E.E. Martlesham Heath.The second prototype (K5179) did not fly until 4th May 1938, and the first production Skua (L2867) flew on 28th August 1938. A total of 190 Skuas had been ordered as far back as July 1936, even before the initial prototype had flown. Thus production was started a full two years after the order. Some squadrons that were meant to have been equipped with Skuas received Gloster Sea Gladiators instead. However deliveries were prompt after that and over 150 had been delivered by the time war started, with all but one being delivered by the end of 1939. This meant that the Skua was very much a "new" aircraft when it first went to war and its pilots were still finding their way in this big metal monoplane aircraft with retractable undercarriage and enclosed cockpits, all a novelty to British carrier pilots of the time. It is interesting to speculate what might have happened if the original expected "in-service" date of 1937 had been kept to. Then the crews would have had two years to get to know their aircraft and the Navy would probably have had 5 or 6 fully equipped and trained Skua Squadrons "ready to go" at the outbreak of war. There would probably have been follow-on orders for a second production run, maybe another 100 or so aircraft, perhaps incorporating minor improvements. As it was, the Skua was viewed as obsolete from the start of its service career and many of the later Skuas (the last 70 off the production line) were delivered from the factory in a yellow and black striped livery for the target-tug role (although many of these were repainted and and served in combat squadrons). Blackburn was keen to get production of the Skua over as quickly as possible so they could concentrate on the twin-engined Botha torpedo-bomber, which turned out to be one of the most disappointing aircraft of the war. The Botha used the same Perseus engine as the Skua and one might speculate those engines might have been better used on more production of the Skua, even if only as target-tugs and training aircraft.

The Skuas wings folded to lie alongside the fuselage to aid in storage in the cramped hanger-space available on aircraft carriers.

Skua in target tug yellow and black stripe livery.

The Skua was designed for operation from aircraft carriers. Its wings folded back to lie alongside the fuselage so that the aircraft could fit onto the lifts of even the oldest of the Royal Navy's carriers. The small floor-space required by the Skua meant more could be carried aboard. The Skua was also built to float on water if ditched, with water-tight compartments to give the necessary buoyancy. There was a dinghy in a compartment in the rear fuselage that was released by pulling a cable (although it didn't always work - read a description of using it in "Oh Calamity!").

Skua landing on board an aircraft carrier. Note the extended "Zap" flaps which doubled as dive-brakes and the extended "V" frame arrestor hook.

The Skua had a major disadvantage in that it been designed without any armour protection for the crew or self-sealing fuel tanks to cope with bullet and shrapnel holes. An armoured windscreen and some armour plate behind the pilot was provided for combat squadrons in late 1940, but the poor TAG in the rear seat had no such protection and faced being roasted alive by the blow-torch flames of a burning fuel tank blown back by the airflow (although he did have a fire extinguisher to attempt to fight any such fire). It is reported that before each combat mission the TAG had to sign for a small bag which contained corks of various sizes with which he was expected to plug any bullet holes in the fuel tank! ³

Considering the small production run of only 190 aircraft (a tiny number compared with most service types of WW2) the number of combats the Skua was involved in is phenomenal. See the "First Blood", "Norway", "Mediterranean" and "Dunkirk" pages for more details...

Skuas continued in use, in dwindling numbers, for fleet requirement duties and as target tugs, until 1944. A few Skuas saw service in Malta, Egypt and Kenya. A very few were still flying into 1945, with the last serviceable Skua being either L3011 in April 1945 or L3034 in March 1945. Today, there are no surviving whole Skua airframes. The mangled wreck of Skua L2940, recovered from a Norwegian fjord, is preserved at the Fleet Air Arm Museum at Yeovilton in the UK. Another recovered Skua (L2896) was being renovated at the Norwegian Aviation Museum at Bodo. However, the project has stalled until other rebuild work being done by the museum is finished and funds and staff become available.

Blackburn Skua Specification.

Engine: Bristol Perseus XII nine-cylinder, sleeve-valve, air-cooled radial engine rated at 815 hp (could give a higher power rating of over 900 hp for 5 mins on emergency boost).

Max Speed: 225 mph (362 kph) at 6,700 ft, 204 mph (328 kph) at sea level. A "maximum" cruising speed of 187 mph (301 kph) was advised, although the best speed for maximum range and endurance was a modest 114 mph (183kph) .

Service ceiling: 20,500 ft (6,248 metres) reached in 43 mins, the Skua had a very poor rate of climb.

Total fuel: 163 imperial gallons (741 litres, 196 US gallons), giving a maximum range of some 760 miles (1,223 km), an endurance of over 4 hours.

Max Speed: 225 mph (362 kph) at 6,700 ft, 204 mph (328 kph) at sea level. A "maximum" cruising speed of 187 mph (301 kph) was advised, although the best speed for maximum range and endurance was a modest 114 mph (183kph) .

Service ceiling: 20,500 ft (6,248 metres) reached in 43 mins, the Skua had a very poor rate of climb.

Total fuel: 163 imperial gallons (741 litres, 196 US gallons), giving a maximum range of some 760 miles (1,223 km), an endurance of over 4 hours.

Armament: Four Browning .303 machine guns in wings with 600 rounds per gun (nearly double the number of rounds-per-gun of a Hurricane or Spitfire). One Lewis .303 machine gun in rear cockpit (whenever possible the gunner would try to replace this with a Vickers "K" gun which was more reliable and had a higher rate of fire). One 500 lb (227 kg) semi-armour-piercing (SAP)¹ bomb or one 250 lb (113 kg) general purpose (GP) bomb recessed under the fuselage and held in a bomb crutch to swing it clear of the propeller in dive-bombing attacks. A "light series carrier" bomb rack could be fitted under each wing. Each carrier could hold 4 x 24 lb (11 kg) Cooper bombs or four 30 Ib (13.5 kg) incendiaries or two 40 lb "stabilised" GP bombs (although the 40 lb bomb seems to have been little-used by the Royal Navy). Some reference books mistakenly give the impression the light series bomb racks were only ever used for "practice" bombs, but they were widely used for belligerent purposes during the first three years of WW2. The 500lb SAP bombs were usually reserved for use against armoured warships, for attacks on merchant ships and ground targets the normal bomb load was a 250 lb bomb in the fuselage recess and 24lb bombs on the light series carriers. The 250 lb bomb had only a little less explosive content than the 500lb SAP bomb (the extra weight of the latter was down to the casing, needed to punch through armour). If used against ground targets the SAP bombs would often bury themselves deep before exploding, reducing the blast effect. The small and largely ineffective 100 lb (45 kg) anti-submarine (AS) bomb, as used in the Fanad Head incident ,could also be carried in the fuselage recess.

Notes on Skua serial numbers.

Notes on Skua serial numbers.

The two Skua prototypes had the serials K5178 and K5179.

Production Skua serials, were allocated in 4 production batches; all consecutive, running from L2867 through to L3056

First batch 69 aircraft - L2867 to L2935 - first one delivered 14/9/38. Photographs show L2867 through to L2929 have two landing lights, one on each wing. At some stage during the production of this batch the style of pitot tube switched from "two-pronged" to "single prong".

Second batch 21 aircraft - L2936 to L2956 - first one delivered 25/4/39

Third batch 50 aircraft - L2957 to L3006 - first one delivered 25/5/39, first Skua target-tug to be delivered was L2987

Fourth batch 50 aircraft - L3007 to L3056 - first one delivered 8/8/39 - last one delivered 10/3/40

The last Skua L3056 seems to have been kept back by the manufacturer for some reason as the second-to-last was delivered in December 1939.

Skuas saw combat until the end of 1941, however, they continued to give service as target tugs, advanced trainers and for fleet and army co-operation duties for the rest of the war in dwindling numbers. The last Skua to be retired seems to have been L3011 in April 1945.

Please note this is only one of many pages on this website dealing with the Blackburn Skua. To see a full list of them <CLICK HERE>.

NOTES

¹ Armourers who served with Skua squadrons interviewed by Matt Willis for his book on the Skua and Roc were adamant that a full Armour-Piercing (AP) 500 lb (227 Kg) bomb existed and was used in the attack on the Scharnhorst. It was reportedly identical in shape to the 500 lb Semi-Armour-Piercing (SAP) bomb. However, no official mention or listing of such a weapon has been found.

² Later in the war, the R1110 receiver was replaced in Royal Navy use by the R1147 which could be operated by the pilot and could therefore be used in single-seat fighters. For a technical description of the Type 72 beacon and the R1110 receiver see this document <click here>.

³ An account of the "bag of corks" is found in Chapter 1 of Stuart E. Sowards book about R.E. Bartlett "One Mans War". ISBN 0-9697229-3-1, Published by Neptune in Canada.

Wartime aircraft identification film of the Skua

Copy of Øyvind Lamo's excellent "Operation Skua" web site archived on the "Wayback Machine".

Copy of Øyvind Lamo's excellent "Operation Skua" web site archived on the "Wayback Machine".

Page revised January 2026.