Dinger's Aviation Pages

Bf 109 Armament

GUNS

At the end of the First World War, the standard fighter armament was two rifle-calibre machine guns in the fuselage, firing forward through the propeller using an interrupter gear to prevent the propeller blades from being shot off. When the Luftwaffe asked for a new fighter design in the mid 30's they stuck to this configuration in the specification. Messerschmitt, therefore, mounted two MG 17 machine guns on the top of the 109 engine. The placement of the fuel tank behind the pilot meant there was a lot of space for ammunition for these two guns. The guns were slightly staggered so that each ammunition box could take up the whole cross-section of the fuselage, thus an amazing 1,000 rounds could be carried for each gun, much more ammunition than contemporary fighters. The British Spitfires and Hurricanes carried only 350 rounds per gun but each had a total of eight guns mounted in the wing outside the propeller arc. Although the German pilot could have kept his finger on the trigger for over three times longer than his RAF counterpart the stream of bullets produced was small compared with the British pilot's eight-gun battery. This was seen even in the prototype stage of the 109's development, and Messerschmitt's design team set out to rectify the problem.

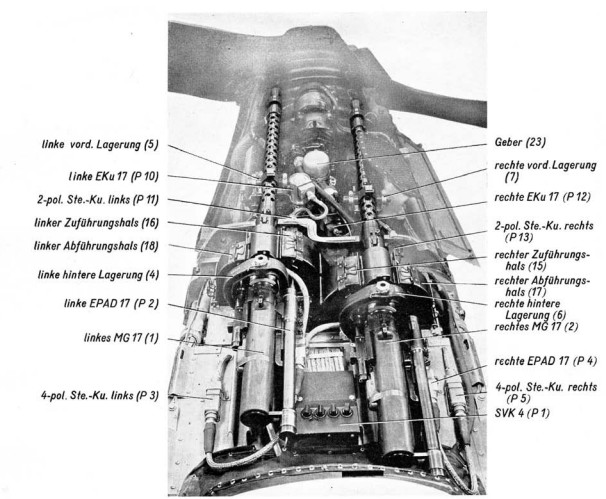

A diagram from a Luftwaffe manual on the Bf109 B, showing the way the two fuselage MG 17machine guns were staggered. This meant each ammunition stowage box could take up almost the whole fuselage cross-section, allowing for 1,000 rounds of ammunition for each gun. This was a very large quantity of ammunition per gun compared with other fighter aircraft of the same period. The ammunition used by the MG 17 came on flexible metal belts (the "Gurt 17"), rather than the disintegrating metal-clip belts used by the British. This meant the belt was retained inside the aircraft after the ammunition was fired..

The first step was to mount another MG 17 machine gun between the two cylinder banks of the 109's engine. The main shaft was already out of line with the axis of the propeller, driving it through gears, so it was a simple task to make the propeller hub hollow to allow the machine gun to fire through it. Now the 109, in its Bf109 B form, had three machine guns, still not enough to match the British. However, in use, the hub-mounted machine gun was found to be unreliable, so it was usually removed.

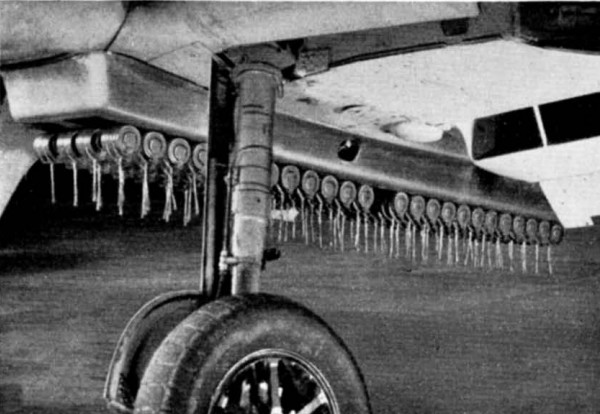

Next, the design team switched their attention to where the British had mounted their guns - in the wings. However, the thin wings of the 109 were the main contributing factor to its flying qualities, and to radically change them would have endangered the whole 109 programme. There was enough room to fit an MG 17 machine gun inside the wing, but not enough room for any sizable ammunition magazine. The result was a bizarre feed system that involved the ammunition belt being fed the whole length of the wing, over a roller, and back to the gun. This enabled 500 rounds to be carried for each wing gun. This meant that the Bf109 D and E-1 versions actually carried more ammunition than a Spitfire or Hurricane, but the weight of fire delivered per second was only half. What could be done now?

As the 30s wore on, the realisation had grown in many countries that machine guns may not be enough to bring down modern metal aeroplanes, particularly if they had armour plating protecting their vital parts. Foremost in research in this area were the French and Danish. The aircraft-mounted cannon that fired a heavy, exploding shell seemed to offer the answer. The Germans saw their chance to leap ahead of the RAF in the firepower stakes, although the need to stay ahead of the French was probably foremost in their mind. The Germans modified the Swiss Oerlikon anti-aircraft cannon to be mounted in aircraft. They had to cut down the weapon's muzzle velocity in the process, which restricted its range and killing power. Called the MG FF, the cannon was fitted in place of the Messerschmitt's wing machine guns, and could also be fitted to fire through the propeller hub. In the wing fitting the ammunition drum meant that a bulge had to be made under the wings; even so, only 60 rounds were carried per gun. The engine-mounted MG FF was prone to vibration and overheating, and seems to have never been used in combat by any E-series Bf109. The MG FF wing cannon was first used in the E-3 variant. The later E-4 version introduced the MG FF/M version of the cannon that fired a thin-walled shell with more explosive power. It meant that the weight of fire of the 109 had jumped from half that of the British fighters to very nearly double it. The cannon was very effective against metal aircraft and was a very good anti-bomber weapon. However, it was less effective against the steel-tube, wood and fabric structure of the British Hurricanes, who could absorb more cannon damage than their monocoque partners, the Spitfires.

There is a mistaken assumption that all the Bf109s used in the Battle of Britain had cannons. This is not so; up to a third of the Bf109s used in the Battle were of the E-1 variant with an armament of just 4 machine guns.

Bf109 E01 of 2/JG52 shot down in1940. The lack of cannons protruding from the front of the wings shows it to have only machine gun armament. It is possible that up to a third of the Bf109s used in the Battle of Britain lacked cannon armament. Although they only had four machine guns compared to the Spitfire and Hurricane's eight, the Bf109 carried more ammunition. The British had 350 rounds per gun, 2,800 rounds in total, while the Bf109 had 1,000 rounds for each fuselage gun and 500 rounds for each wing gun, a total of 3,000 rounds.

In the Battle of Britain, although the destructive power of the German cannon was evident, many Luftwaffe pilots came to appreciate the "blunderbuss" effect of the RAF's eight-gun fighters. Thus, there was something of an outcry when the 109F appeared with only one engine-mounted cannon and the two fuselage rifle-calibre machine guns. Many German aces refused to fly the new machine at first, although the lack of wing armament gave the 109F increased performance, they mourned the loss of firepower. This led to the F-2, in which the 20mm engine-mounted Oerlikon MG FF was replaced with the MG 151/15 cannon. Although of a smaller calibre than the earlier weapon, the 15mm cannon had a higher rate of fire and velocity, making it a much more lethal weapon. The 109 could also carry 200 of its smaller belt-fed shells.

Formidable as the new weapon was, even greater killing power was needed against the heavily armed and armoured American Flying Fortress bombers that began to appear in 1942. To meet this new challenge, an add-on pack for mounting under each wing was designed. Each "Gondola" contained an MG151/20 cannon with 120 rounds. First used on the 109F, the packs were one of many armament options available for the later 109G.

It was in the G and K series that the Messerschmitt fighter reached its peak in firepower and variety of weapons carried. Starting with the G-5, the two 7.9 mm rifle-calibre machine guns mounted above the engine were replaced with two MG 131 13mm heavy machine guns; these new weapons had much greater range and punch than the earlier guns. Range is something that is very desirable in a fighter's gun system. Although the fighter pilot's maxim was always to get in as close as possible, we can all see the attraction of a weapons system that will allow you to stand back out of the range of a defending bomber's gunners but still score hits with your own weapons. The MG 131 could fire both explosive and armour-piercing ammunition, making it a very deadly weapon. The American bombers were all equipped with .50-inch calibre guns of very similar performance to the German 13mm guns. However, throughout the war, RAF bombers largely stuck to rifle-calibre .303-inch guns with a shorter range than either the German or American weapon, thus putting them at a severe disadvantage. When fitted with 13 mm guns, the Bf109 had two large blisters ahead of the cockpit over the breech blocks. This gave rise to the nickname "beule", German for "bump". Later in the war, the blisters were done away with by the adoption of the "Type 110" engine cowling that was slightly asymmetrical.

The G series could take a whole series of different "Rüstsätze" kits for modification in the field or "Rüststand" and "Umrüst-Bausätze" options for factory installation. Foremost amongst these were the gondolas for the 151/20 cannon previously mentioned. There was also a kit which gave the 109 two tube-launched 21cm WGr rockets, used against bombers, they gained the name "pulk-zerstorer", which is "formation destroyer". The amazingly destructive Mk 108 cannon, probably the ultimate German aircraft gun system of the war, was used as the engine-mounted cannon first used in the Bf109 G-6/U2 model, and the same weapons could be carried in underwing gondolas in the RIV Rüstsätze field modification.

Bf109 with 21cm rocket tubes beneath the wings.

A Luftwaffe reconnaissance unit in France experimented with a belly pack containing two backwards-firing MG 17 rifle-calibre machine guns to protect from attacks from the rear.

The massive high-velocity MK103M 30mm cannon was developed for use in the K series but was never used in combat and may have only flown in a single prototype installation. Although devastating if it hit anything, its rate of fire and accuracy were found to be too low for practical use.

So by the end of the war, the G and K series aircraft could carry up to three 30mm cannon and two 13mm machine guns, a potent anti-bomber combination, but the extra weight degraded performance compared with Allied fighters. This led to the formation of units equipped with 109s fitted with only the fuselage guns and the single engine-mounted cannon, to take on enemy fighters.

BOMBS

When bombs are fitted to fighter aircraft, it is a sign of either confidence or desperation. The job of the fighter is to shoot down other aircraft, and only two conditions should prompt their use as bombers. The first is where air supremacy has been achieved, and there are no airborne targets for the fighter's guns. In this case, if only to give the fighter pilots something to do, the use of fighter-bombers is obviously a good use of the available resources. The other condition is one where the enemy has obtained a large measure of air superiority and your own bombers have been destroyed on the ground or are shot down before they can reach their target. Here again, fighters carrying bombs can be used as the only way of striking at the enemy.

Fitting a bomb to a Bf109

The Germans experienced both conditions during the war and made widespread use of the Bf 109 as a fighter-bomber or "Jabo". During the Battle of Britain, use was made of E-1 and then E-4/B models as fighter bombers. This was at first done in an experimental role by the Luftwaffe's elite trials units Eprobungsgruppe 210 and Lehrgeschwader 1. As the Battle drew to a close, and German bombers began to take unacceptable losses, the use of the Bf109 as a "hit and run" bomber grew. The Germans saw it as a way of keeping the pressure on Britain, but it was probably counter-productive in that the British saw it as an act of German desperation. In any event, by the end of the Battle. one Gruppe in each fighter Jagdgeschwader was equipped for the Jabo role.

The most telling use of the 109 in the fighter-bomber role was the opening of the attack on Russia. With complete surprise, the 109s participated, with bombing and strafing attacks, in the destruction of the Russian air forces along the Soviet border. Caught on the ground, the Russian air regiments were largely annihilated.

As the war turned against Germany, the 109 was used more and more to try to strike at Allied ground and sea forces, a job that the Luftwaffe's twin-engined bomber force found more and more suicidal as the opposing fighter arms grew. The last great attack of the Luftwaffe was an attempt to emulate their great opening victory against the Russians, but this time against the British and Americans in Northern France and the Low Countries. On New Year's Day 1945, the Germans launched masses of Bf 109s in Operation Bodenplatte (Ground Plate) against the Allied Air Forces. Although they achieved complete surprise, the Germans still lost more aircraft themselves than they destroyed on the ground. How things had changed for the once-mighty Luftwaffe.

The bombs carried by the 109 were at first a single 250 kg (550lb) high-explosive, semi-armour-piercing or incendiary bomb, alternatively four smaller 50 kg (110lb) bombs could be carried. With a special bomb rack fitted, the Bf109 could carry up to 96 of the small SD2 "Butterfly" bombs. Later bombs of up to 500 Kg (1,100lb) could be carried, but a special jettisonable wheel had to be fitted under the fuselage to give the ground clearance needed (some sources imply this was only done on a single prototype and never used in action).

BF109 carrying 96 of the small SD2 "butterfly" fragmentation bombs

If a 500 kg bomb sounds big, how about a bomb weighing over 13,600 kg (30,000lbs) with nearly 3,600 kg (8,000lbs) of that made up of explosive? That was the idea behind the "Beethoven" and "Mistel" composite weapons. An unmanned Junkers 88 twin-engined bomber had a Bf 109 attached to it by struts on top of the bomber. Controlled by the pilot in the 109, the whole combination took off under the power of all three engines. Over the target, the pilot lined up the Ju 88 and then detached. The weapon was used against the invasion fleet off Normandy following D-Day. It seems that HMS Nith, a floating headquarters, was forced to withdraw to harbour following splinter damage from a Mistel (the Nith's crew thought that a normal German bomber had crashed nearby). The Germans also hit the Free French ship "Courbet" with a Mistel, but since the Courbet had previously been deliberately sunk as part of the barrage for the Mulberry harbour, it hardly counts as a success! As the war drew to a close, the Germans planned one huge act of revenge against the Russians by launching Operation "Eisenhammer" (iron hammer), a massive Mistel attack against all the major hydroelectric plants in Western Russia. This would have crippled the post-war economy of the Soviet Union for many years. In the event, the Mistels that had been carefully husbanded for Eisenhammer were thrown away in an effort to destroy Russian crossing points on the Oder River instead.