Dinger's Aviation Pages

The Boulton Paul P92 Project and F11/37.

The story of the cannon-armed successor to the Defiant turret fighter.

Revised in March 2023 with information provided by Les Whitehouse.

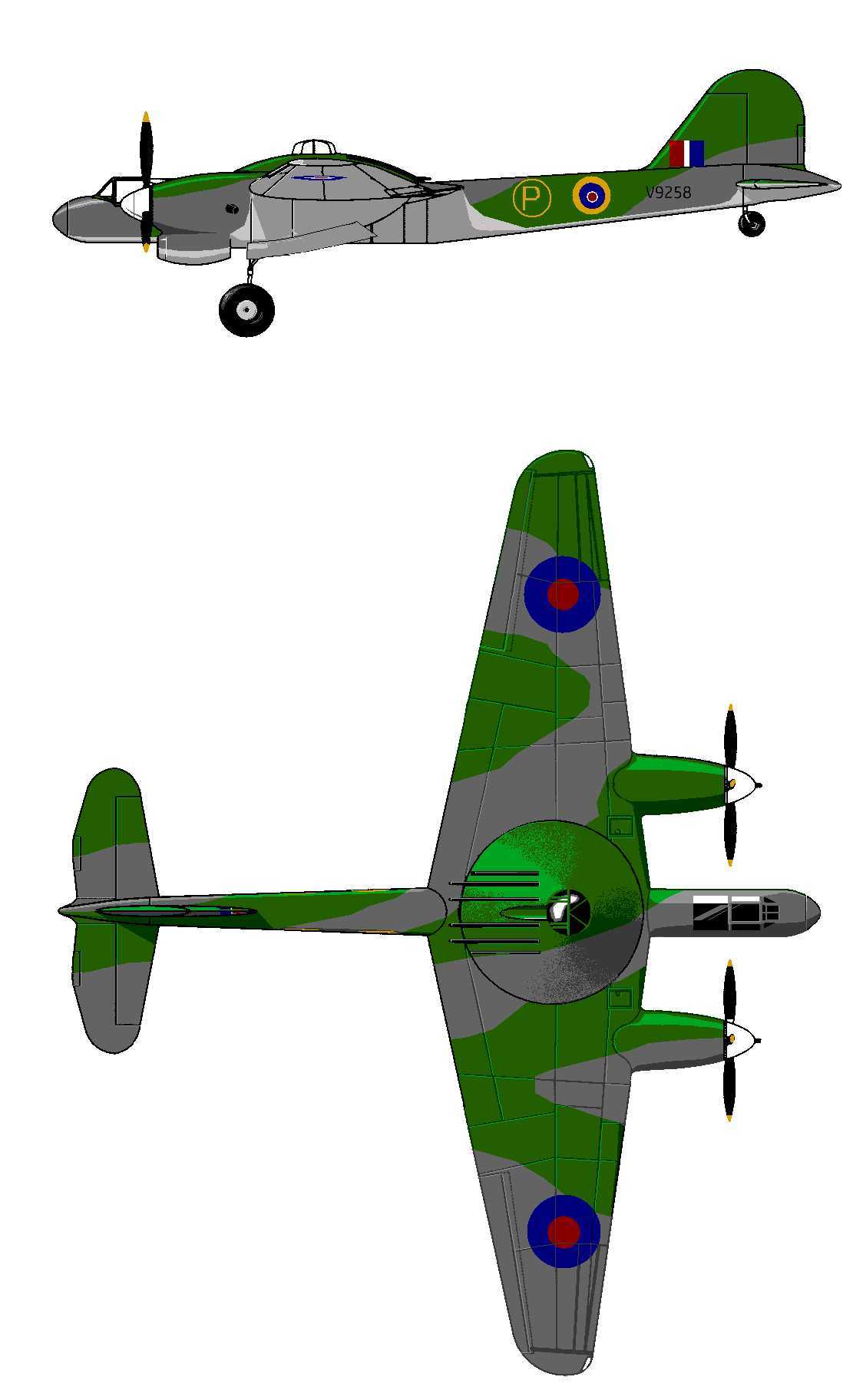

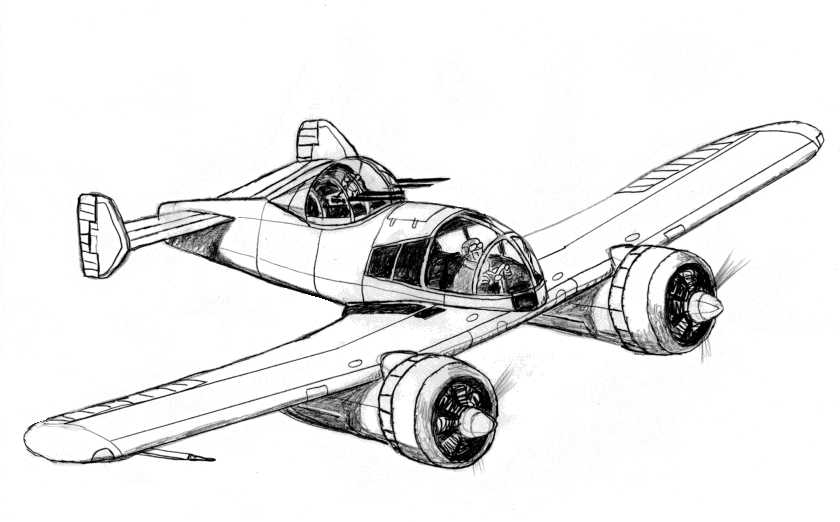

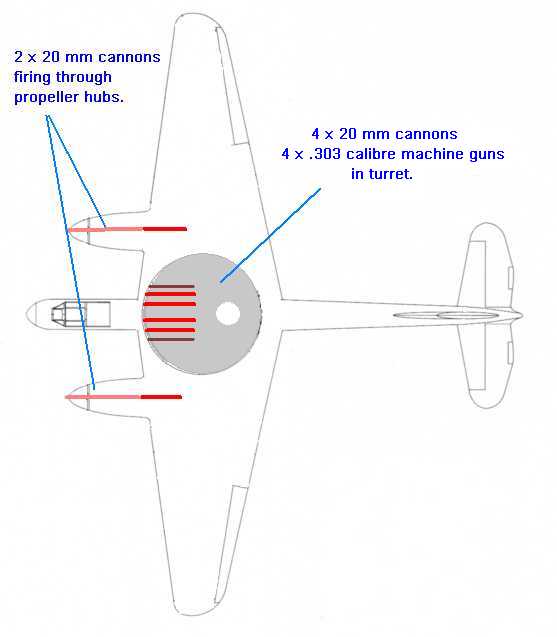

Boulton Paul's P92 project, in its final form, with a revised turret with extra machine guns. The outline was substantially different to the initial tender. This represents the Sabre-engined version with submerged exhausts. Serial number V9258 was allocated to this particular prototype.

In the 1930s there were all sorts of competing ideas about what future aerial warfare would be like. The British Royal Air Force favoured strategic bombing by self-defending formations of unescorted bombers in daytime and lone bombers at night. It was only natural that the RAF should favour fighters that would perform best against the types of bomber it used itself (or hoped to deploy)¹. It was thought unlikely that German bombers would be escorted by fighters, and certainly not by nimble single-engined fighters (that would imply the collapse of the French defences of the Maginot line and the Belgium frontier forts, politically unthinkable at the time). To attack the massed defensive firepower of a daylight bomber formation was thought to be suicidal for single or small groups of fighters, so the RAF adopted the complicated "Fighter Attack Plans", a series of rigorously rehearsed, set-piece attacks to be carried out by tightly packed flights or squadrons in formation². This was hoped to split the defensive fire of the bombers. To aid the attack by formations of single-seat fighters with eight machine guns apiece (Hurricanes and Spitfires), another type of fighter would attack the bomber formation from underneath or the sides, to further split the bomber's defensive fire. Attacks from below would be done using the "no-allowance sighting" method, a somewhat counter-intuitive, but fully tested, means of shooting with greater accuracy over longer ranges. This function was to be done by flights or squadrons of two-seat Boulton Paul Defiant fighters, which mounted their armament of four machine guns in a rotating turret. It should be noted that the Air Ministry had originally thought a twin-engined design would be required to mount a turret and still give the performance required to intercept enemy bombers and had contracted the Gloster Aircraft company to build a prototype against specification F34/35. But the Gloster project was cancelled when the Defiant promised to provide the performance required with a single engine.

A Boulton Paul Defiant turret fighter, flying over Belvide Reservoir and the A5 Watling Street, not far from the Boulton Paul factory and airfield at Pendeford.

Spitfire and Hurricane developments were kicked off by Air Ministry specifications issued in 1934 while the Defiant was initiated by a specification issued the following year (1935). However, the Air Ministry was concerned that machine guns were not going to be able to bring down the fast, all-metal bombers that were expected to appear shortly. Thus, in 1935 they issued another specification for a fighter to be armed with four 20mm cannons. This was initially meant to be a single-engined type. Boulton Paul designed their P88 single-engined fighter with four cannons in the wings to meet the specification and for a time it was the front-runner for selection. However, the Air Ministry switched their support to the twin-engined Westland Whirlwind cannon fighter. Having initiated the development of a fighter with forward-firing cannon armament it was only natural for the Air Ministry to consider another design with the cannons mounted in a turret to complement it.

Specification F18/36 and the Boulton Paul P89.

Little is known about Air Ministry specification F18/36, other than it was for a two-seat fighter which would have logically meant some type of turret fighter, probably with cannons. The specification seems to have been abandoned after the Air Ministry consulted various aircraft companies about it. All the British aircraft companies were then struggling to produce the aircraft types already on order and had little capacity for further designs. What is known is that in this exact period, Boulton Paul worked on a project called the P89, a twin-engined turret fighter, to be powered by twin Rolls Royce Kestrel XVI engines. It had a shallow "conformal" turret, for which Boulton Paul applied for a patent. Only a portion of one diagram survives, but the P89 seems to have all the features that would characterise the later P92, but in a smaller airframe. It is not clear if the turret would have contained machine guns or cannons, or how many.

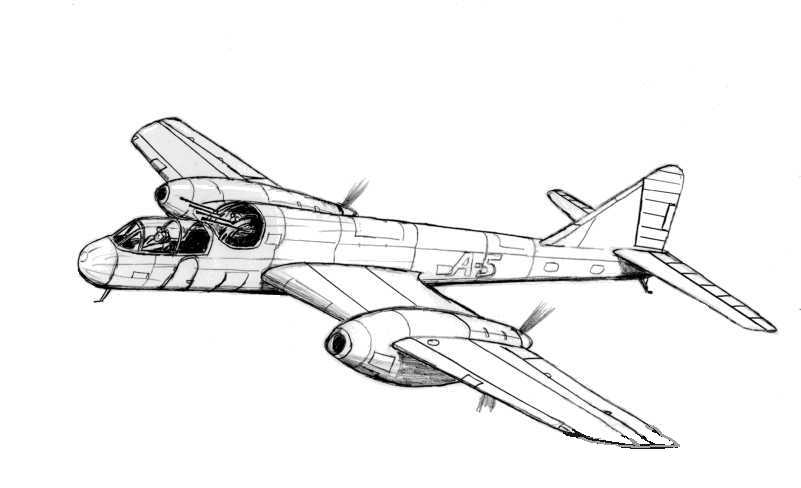

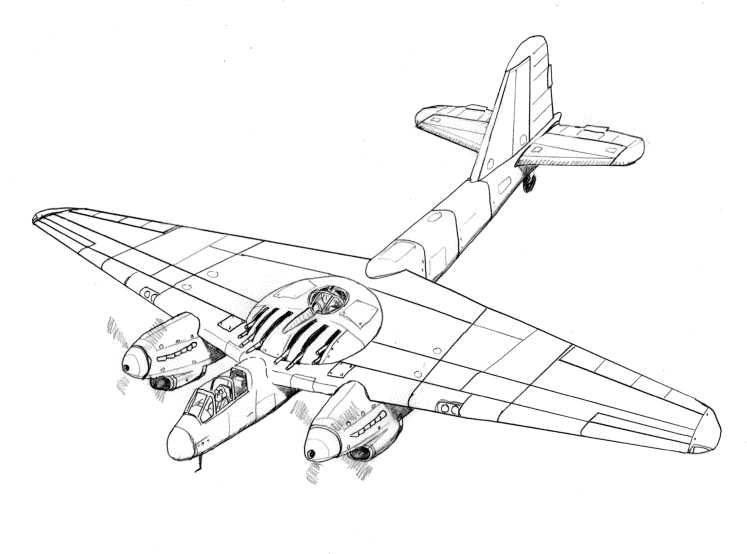

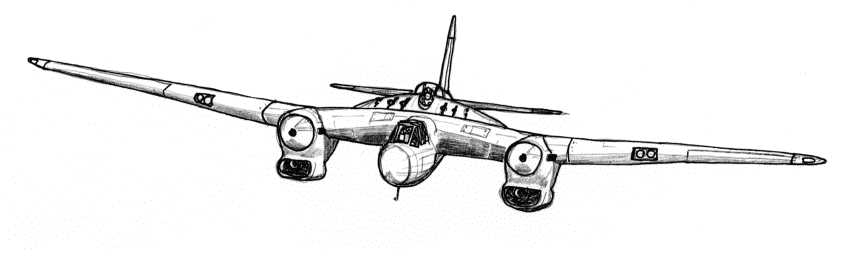

The competition from Gloster: Specification F9/37

You will remember that Gloster had been working on a twin-engined design with a turret, for Air Ministry Specification F34/35, which was cancelled because of the promise shown by the Boulton Paul Defiant. Gloster had continued to work on the design and produced the outline of an aircraft that would have two cannons mounted in the fuselage and a turret with machine guns. Gloster was one of the few British aviation companies with spare capacity in their design department; although it was already part of the larger Hawker-Siddeley group it had managed to retain its own design office despite the loss of its top designer, Henry Folland. The Air Ministry wrote a detailed specification (F9/37) around Gloster's design and awarded a contract to Gloster straight away. The first of two prototypes flew in April 1939. A neat, streamlined design powered by two Bristol Taurus radial engines it had a slightly bulged fuselage to accommodate a turret, presumably a Boulton Paul Type "A" turret with machine guns as used on the Defiant. It had space for two cannons in the nose, these were angled to fire upward at a "no-allowance" angle of 12 degrees. The first prototype was never fitted with a turret or cannons, it was badly damaged in a landing accident. A second prototype was powered by Rolls Royce Peregrine engines, giving a somewhat decreased performance. The second prototype was fitted with armament, but not in a turret. Instead, three upward-firing 20mm cannons were fitted into the fuselage where the turret had originally been meant to go. Together with the two upward-firing cannons in the nose, this gave Gloster's F9/37 fighter a formidable armament of five upward-firing cannons. However, the Gloster F9/37 seems to have been seen by the Air Ministry as only a stop-gap for a far more ambitious aircraft with better performance.

This image of the Gloster F9/37 shows the bulged fuselage aft of the front cockpit meant to accommodate a turret. Instead, the second prototype was fitted with upward-firing cannons in the space originally meant for the turret. The first of two prototypes, with Taurus engines, had a remarkable top speed of 350 mph (563 kph). The second prototype, with lower-powered Peregrine engines, could only manage 330 mph (531 kph). The original Air Ministry F9/37 had only called for a speed greater than 300mph (483 kph).

F11/37, a new level of performance and armament.

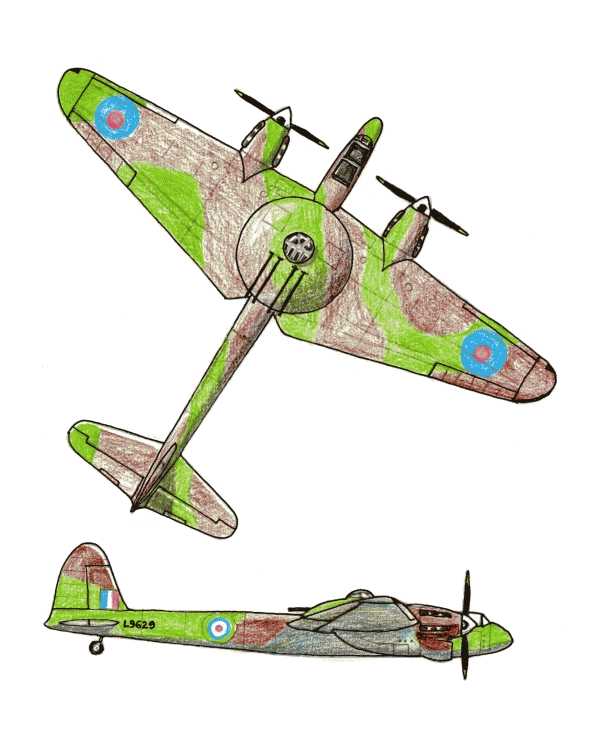

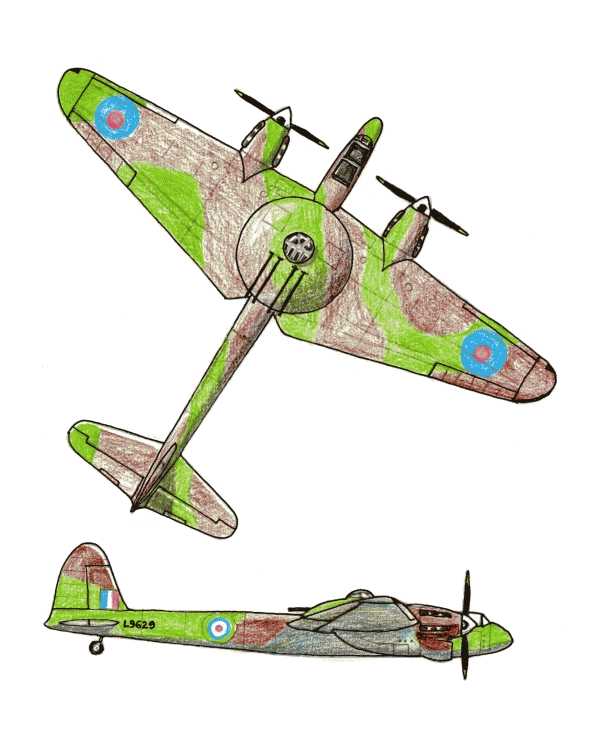

An image based on Boulton Paul's early submission of the P92 project to the Air Ministry. Wind tunnel testing and refinements led to substantial changes.

An image based on Boulton Paul's early submission of the P92 project to the Air Ministry. Wind tunnel testing and refinements led to substantial changes.

At the same time as the F9/37 contract was given to Gloster, the Air Ministry issued a much more pioneering specification (F11/37) that demanded unprecedented performance; a top speed above 370 mph and a service ceiling of not less than 35,000 feet being called for. Endurance for a typical "interceptor" mission was to be about 2 hours, with a slightly extended period for lower-speed patrols. More importantly, the armament was to be four 20mm cannons in a rotating turret with 60 rounds of belt-fed ammunition per gun. An amendment was issued soon afterwards that the belt-fed cannon would not be available and that the turret should be designed to use the Hispano 20mm cannons with drum magazines. No particular type of engine was specified, other than it should be a British engine "of the latest type". The specification led to tenders from many companies. Along with the P92 proposal from Boulton Paul, there were projects put forward by Hawker, Bristols (who tendered two different designs) and Armstrong Whitworth. Also, Avro, Fairey and Short Bros all worked on designs for F11/37 but did not seem to have officially tendered them. The specification did not specify that the turret should have an all-round traverse, the Bristol and Armstrong Whitworth designs featured turrets that only operated in the forward hemisphere, ideal for "no-allowance" attacks but unsuitable for "broadsides" or defending against an attack from the rear.

The Armstrong Whitworth design for Air Ministry specification F11/37 was powered by two Merlin engines in a "pusher" configuration. Its armament of four 20mm cannons was accommodated in a turret that could only be rotated around the forward hemisphere. The cannons could not be depressed far enough to fire horizontally, clearly showing it was intended to be used in no-allowance attacks.

The Bristol tender to specification F11/37 came in two versions. The first had a pair of Hercules engines and a second "scaled up" version with two of the bigger Centaurus engines. Both featured a turret with four 20mm cannons that could only be operated in the forward hemisphere. The design was similar in layout to the Grumman XF5F Skyrocket, although much larger.

The Boulton Paul P92. This drawing shows the planned outline late in the project's life, with Napier Sabre engines with forward-firing cannons firing through the airscrew hubs and extra machine guns in the turret. The turret had a trough in it to give a better view for the gunner. The fuselage was more angular and the rear fuselage had a slight upward slant

Again, the Air Ministry was building a complimentary set of fighter aircraft to defeat incoming formations of bomber aircraft, that in the future might themselves be defended by cannon armament and therefore needed cannon-equipped fighters to defeat them. The same year as the F11/37 specification was released another specification (F18/37) called for a single-engined fighter with a forward-firing armament of four 20 mm cannons, this was to result in the Hawker Typhoon. So the machine gun armed Hurricane/Spitfire and Defiant combination was to be replaced by the cannon-armed F11/37 - Typhoon combination.

The Boulton Paul response, designed by JD North and HA Hughes, was the P92. It had the "conformal" saucer-like low-drag turret first developed for the aborted P89 design. This housed four 20 mm Hispano cannons in slots and had an all-around traverse. The gunner's head protruded inside a small perspex blister set slightly back from the middle of the turret. Boulton Paul allocated the turret the "Type L" designation. The engines were to be either Rolls Royce Vultures or Napier Sabres. The pilot sat in the nose with an excellent view forward but the view sideways was somewhat blocked off by the engines (Sabre engines would have protruded slightly further forward and blocked off more of the view than the Vulture engine installation). The pilot and gunner were provided with separate hatches in the floor to bale out of in an emergency, the gunner could also jettison his blister and escape that way. The pilot's seat could be made to tip back and automatically release the bottom hatch so that he could slide down, head-first, out of the aircraft. The setup for the pilot has come in for some ridicule on the internet, but it was in many ways superior to the method on the Beaufighter and Mosquito. Boulton Paul built a rig to test the principle, which was tried out by the designer JD North himself. Although the system worked perfectly, the mat that should have cushioned North's fall had been inadvertently removed and he had a bit of a sore head afterwards! Nevertheless, the escape mechanism was deemed a success. The pilot would also have had push-out panels in the canopy to escape from the aircraft in the event of a crash-landing or ditching at sea, the same as in the Beaufighter and Mosquito.

The P92 "Navigator" Myth.

Many articles state that the P92 was designed to carry a navigator behind the pilot. None of the surviving Boulton Paul diagrams or descriptions of the design shows any provision for a navigator. There was indeed a space behind the pilot that looks suitable for housing another crewman but it is into that space that the pilot's rearward sliding seat moved for emergency bale-out. The myth arose in 1943 when "Flight" magazine published an article hinting at the secret P92 project, seemingly based on rumours that it was to be used as an escort fighter for missions over Europe with a range of an astonishing 2,000 miles and would therefore require a navigator. The article then spawned at least one artist's impression showing an extended canopy behind the pilot to house a navigator. This has rather coloured descriptions of the P92 ever since, from its description in Putnam's book on Boulton Paul Aircraft to videos about the P92 on the internet.

The article may even have been deliberate misinformation to divert German resources into guarding against USAAF or RAF bomber raids being escorted by such aircraft. It is also intriguing that at about the time the article appeared, after having languished at Boulton Paul for two years the P92/2 prototype was sent to A&AEE at Boscombe Down for evaluation. It would be prudent of the British intelligence services to assume that any German spies operating in the UK would keep the airfield at Boscombe Down under observation and therefore observe the P92/2 being flown, giving weight to the rumour of a turret fighter being prepared for service. There are other examples of this type of subterfuge being employed, for example, a B29 Superfortress was flown to Britain and widely photographed to give the impression that B29s were going to be used against Germany.

The long-range "navigator" story was ignored in Tony Buttler's books that mention the P92 and thoroughly debunked in Les Whitehouse's book on Bouton Paul (see sources listed below).

If the P92 had entered service as a night fighter it would have needed a radar operator (the nose of the P92 would have been ideal for housing a centimetric radar as used on the Mosquito). It would have made sense to place a third crew member further back in the main body of the aircraft, where they could have shared the hatch on the floor that the gunner used.

The Air Ministry very quickly latched onto the P92 as the best offering for F11/37. One of the reasons for this was that the turret would also be suitable for arming the next generation of British bombers, which the Air Ministry hoped would have cannon armament to defend themselves. Work on this was going ahead in the late 1930s and would manifest itself in Air Ministry specification B1/39 for a bomber to replace all the heavy and medium bombers then currently in use or on order. The front-runner for this tender was the Bristol Type 159 "Beaubomber". Although it featured Bristol's own design of four-cannon turrets for both dorsal and ventral positions, the dorsal turret looked almost identical to that on Boulton Paul's P92 fighter and would have been made interchangeable (Boulton Paul allocated the designation "Type M" for the turrets modified for the Beaubomber). Air Ministry Specification R5/39 for a four-engined flying boat to supplement or succeed the Short Sunderland was revised in April 1939 to specify a 4-cannon turret in a dorsal position. Outline plans for all the designs submitted show turrets that look to be of the Boulton Paul Type M design (the Short R5/39, the Supermarine 328, the Blackburn B32 and the Saro S38 and S39).

Bombs?

One of the stranger aspects of the P92 design was the requirement for a small bomb bay in the fuselage. This has mistakenly been reported to be designed to house a single 250 Ib bomb to be dropped onto enemy bomber formations in an attempt to hit one of the bombers. Such a tactic is rightfully derided. Both the Germans and the Japanese did attempt to use this method against Allied bombers, with poor results. The German Ace, Heinz Knoke who proposed the tactic to the Luftwaffe, did succeed in bringing down a B17 bomber with his first attempt, but the method was quickly dropped by the Germans because of a lack of further success and the weight of the bomb making their fighters easier to intercept by American escort fighters. In fact, in the 1930s, the British had thoroughly investigated this method of attacking enemy bombers because it was one of the pet theories of Frederick Lindemann (later Viscount Cherwell), who had an influential seat on the "Committee for the Study of Aerial Defence". Starting in 1937 and continuing through into 1938 the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) ran experiments with what they termed "Scatter Bombs". The F.11/37 specification was drawn up when these experiments were going on and Boulton Paul's blueprints show the bomb bay on the P92 housing, not a single bomb but a " small bomb container" (SBC), essentially a big box containing a number of these bombs. They were used throughout the war, usually for dropping incendiary bombs. However, they were also used for the trials of the Lindemann bomblets. The experiments showed that the chance of one of these bomblets hitting a bomber was negligible, while the explosive charge of individual bomblets would do almost no damage to the target bomber even if they did hit. In fact, the bomblets were deemed to be more of a danger to the aircraft carrying them. Because they were too small to have a traditional fuse they were filled with an explosive mixture that would self-ignite when struck hard, meaning the whole lot might go off if dropped accidentally! Lindemann's activities were so disruptive (he was sceptical of the value of radar and was opposed to research into it) that the Committee voted to close itself down and then reestablished itself without Lindemann being invited to join again! However, Lindemann did go on to push through with his idea for "Long Aerial Mines", essentially bombs suspended on long cables from parachutes, again to be dropped into the path of enemy bomber formations. These were used briefly during the war, but only claimed one German bomber (and even that is disputed). The bomb bay was dropped from the P92 prototypes and it is highly unlikely to have been a feature of any production P92.

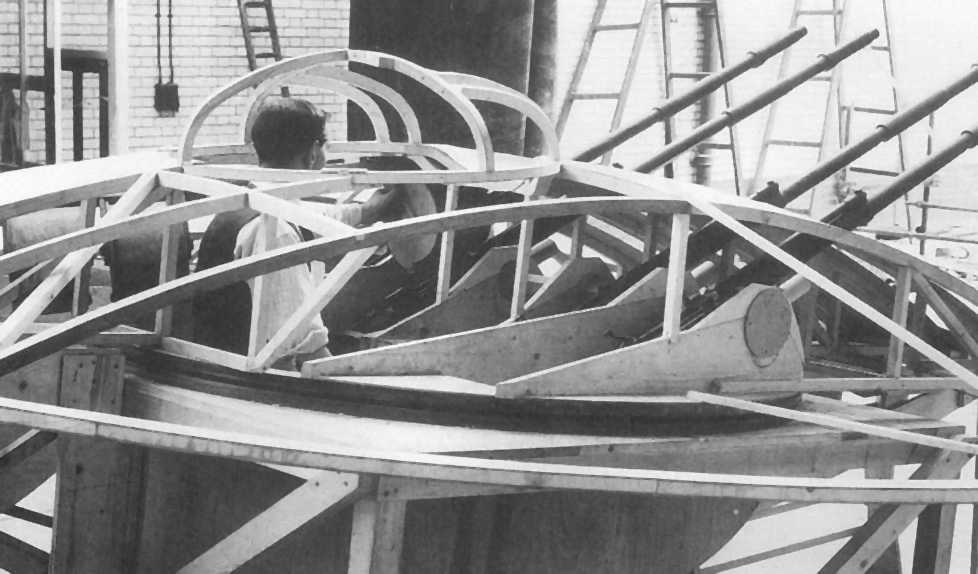

The P92 was to be of stressed-skin construction and have main undercarriage wheels that retracted backwards into the engine nacelles and wings (the wheels would rotate through 90 degrees to lie within the wing behind the nacelles). The engines would have underslung radiators. The Air Ministry thought that the tapered wings might suffer from "tip stall", leading to dangerous stalling characteristics and therefore recommended that leading-edge slots be fitted. The wing and conformal turret were designed as a single aerodynamic unit. It was anticipated that getting the large turret to work was going to be the hardest part of the design. The large turret ring would be in a part of the airframe that was likely to be flexing a lot, likely to cause jamming. A lot of effort was put into making this area of the airframe as rigid as possible. The first attempt failed under testing leading to a redesign. In the meantime Boulton Paul was getting experience with the Hispano 20mm cannon, they mounted one in the nose of one of their Overstand bombers and then fitted one into the turret of a Defiant. The cannon-armed Defiant went off to A&AEE for testing in June 1939. Experience with the cannon-armed Defiant and wind-tunnel testing of mock-ups of the P92 showed that the increase in drag from the cannons when they were rotated to the sides was much greater than anticipated. Boulton Paul began to work on solutions to this problem involving aerodynamic sleeving on the cannon barrels. This issue is given a lot of coverage in some articles about the P92, speculating that the drag of the cannons was a fundamental issue of the P92 that would have blighted its performance if it had gone into service. This ignores the fact that when they were at low angles the cannons were almost completely enclosed inside the slots of the large saucer-shaped turret and thus induced very little drag. Also, drag was not high if the cannons were pointed forward or to the rear. It was only if the cannons were pointed sideways and at a high angle that high drag became a factor. This would have affected the turret's use in bombers, where attacks from any quarter have to be engaged, but would have been less of an issue on the P92 fighter where the cannons would typically be at a low angle during combat. The concern about the drag of the cannons seems to be more about their use in the Boulton Paul "Type H" series of turrets. These were a parallel development of twin-cannon turrets of a more traditional layout that could be used in bombers instead of the existing machine gun turrets. They were planned for use in the Handley Page HP58 "Super Halifax" and as alternative armament for the Short S36 "Super Stirling".

An early wooden mock-up of the P92 turret. Notice the "trough" for the gunner to get a better view, the two dummy cylindrical cannon magazines on the left and the other dummy magazine being placed onto one of the cannons.

The P92 was designed to take either the Rolls-Royce Vulture or the Napier Sabre engines. The Air Ministry initially ordered two prototypes (serial numbers L9629 and L9623), one with each set of engines but the Vulture engine promised to be available much sooner than the Sabre, so they changed the order so that the first two prototypes had Vulture engines and a third prototype with Sabres was added (Serial number V9258). It seems that the Air Ministry saw the production P92 as having Sabre engines because performance estimates predicted it would be faster than the Vulture version. The Sabre-engined version also offered the advantage of extra armament (see the section on armament below). It should be noted that the first prototypes were not expected to be delivered with working turrets, only a dummy "hump". Working turrets would only be fitted later in the test programme.

Most of the 3-view drawings of the P92 available on the internet show a very early outline of the P92 as presented in the tender document sent to the Air Ministry. Wind tunnel testing forced refinements, with a more angular fuselage, a slight angling of the rear fuselage upwards, a differently shaped rudder and the deletion of the cut-outs of the wings at the rear wing roots. The dimensions of the aircraft were also changed from those listed in the tender document. Les Whitehouse's 2021 book (see sources below) contains three-view drawings for both the Vulture and Sabre engined versions when development was halted.

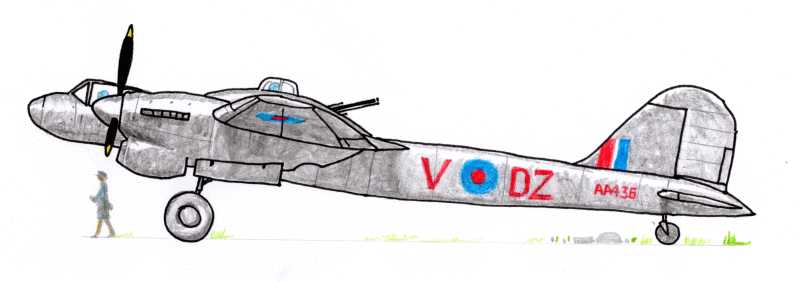

Boulton Paul P92, Sabre-engined version in speculative night-fighter colours (serial and codes were as used by a Defiant night-fighter).

P92 armament - More than just 4 cannons.

The P92 "Type L" turret was designed around four 20 mm cannons. It is evident that the Air Ministry originally thought that these might be fed by belts of cannon shells, but this was not to be as all the cannons available only had provision for drum magazines. The standard drum magazine held 60 shells, only enough for some 5 seconds of firing time. Now that might be just enough for a fighter (the Westland Whirlwind and early cannon-armed Spitfires used 60-round drums), but it certainly would not be enough if the turret was to be fitted into a bomber for defence in its "Type M" form. A 60-round drum was also a heavy item for the gunner to handle and clip into place³. So the Air Ministry decided to use 30-round drums instead. Up to 40 of these lighter drums would be carried in the B1/39 bomber. Although they would allow only a short 2½ seconds of firing time they could be more easily replaced. Boulton Paul designed their cannon turret so that it had a rack for magazines behind each gun, each set of racks held three magazines. With one magazine already in place on the cannon that made a total of 4 magazines for each gun. As each magazine was used up it would be manually unclipped by the gunner and then another magazine would be automatically presented next to the cannon to be clipped into place. Thus each cannon would have a total of 120 rounds available, a total of 480 rounds for all four cannons. However, Boulton Paul designed the racks so that they could also hold the full-size 60-round magazine, doubling the number of rounds to 240 rounds per gun with a total of 960 rounds for all four guns. You can imagine the tactical disadvantage of only having either 2½ or 5 seconds of firing time before having to reload, so Boulton Paul designed a switch box so that each cannon could be selected to fire individually or in pairs, extending the firing time considerably. But it was realised that even this might not be enough, so the turret was redesigned to take an additional four belt-fed .303 Browning machine guns, the same as used in the Defiant turret. The machine guns would be fitted in two pairs outboard of the cannon, each pair in a single slot. With belts of 600 rounds the machine guns would have had a firing time of about 30 seconds. That way the gunner would still have something to fire with if caught between swapping ammunition drums for the cannons. The combined armament of cannons and machine guns would have given the P92 turret devastating firepower.

But that was not all. The Sabre engine had two crankshafts that could have allowed a version to be built with a blast tube through the middle of the engine and out through a hollow propeller hub. That would have allowed a 20mm cannon to be fitted to fire through the propellor, like the French and German "moteur-cannons". Thus the cannon and machine gun armament of the turret could have been supplemented by another two cannons fired by the pilot. You can imagine a scenario where a P92 engages an enemy bomber formation from below with "no-allowance" fire from its turret, then while the gunner is reloading, the pilot brings up the P92 to carry on the attack with the two forward-firing cannons. It should be stressed that the Air Ministry specification only covered the initial 4-cannon armament and any production P92 would have likely been first delivered with that configuration, with the additional machine guns and engine-mounted cannons being later modifications.

The full armament of the P92 could be pointed straight ahead, firing between the two propellers.

The type L turret had a shallow trough in front of the gunner's bubble cupola to improve the view. Automatic cut-outs were to be put in the firing system to avoid the gunner shooting the P92's tail or propellers off. The raising of the tailplane that went along with the redesigned slight upward tilt of the fuselage, placed it directly in the gunner's line of sight so that it took up less of the view. Because of the geometry of the turret, fuselage and tailplane, it should have even been possible for the gunner to shoot underneath the tailplane on either side of the fuselage.

Cancellation.

Any suggestion that the P92 was cancelled because of the perceived failure of the Defiant during the Battle of Britain is wrong. The P92 project was cancelled on the 26th of May 1940. This was four days before the Defiant's "Day of Glory" when 264 Squadron (the first and only Defiant squadron operational by this date), claimed an astonishing 37 German aircraft shot down and another three "probable" over Dunkirk. Although post-war examination of Luftwaffe records shows this to be wildly optimistic, the figure was believed true at the time and seemed to vindicate the hopes for turret fighters. It was only some two months later, on the 19th of July, that the first real indication of the Defiant's inability to tangle with Bf109s was revealed when 141 Squadron, the second Defiant unit to form, was set upon by Bf109s over the English Channel. Six of nine Defiants were lost outright with the remaining three all being badly damaged. That didn't stop 264 Squadron being put back into the front line with No 11 Group until a series of engagements at the end of August saw them come off second-best to Bf109s. Thus it was a full three months after the cancellation of the P92 that the turret fighter concept was called into question for day fighters.

The real reason for the cancellation of the P92 was the creation of the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) under the leadership of Max Aitkin, Baron Beaverbrook in May 1940. Beaverbrook cancelled virtually every aircraft project not already in production, including the Boulton Paul P92, the Bristol Type 159 "Beaubomber" and the Gloster F9/37. Production was to be concentrated on only a few types. The Defiant was one of the aircraft selected for continued and increased production. Thus, perversely, it was the anticipated success of the Defiant that doomed the P92; Beaverbrook did not want Boulton Paul distracted by the P92 project, he wanted all effort concentrated on maximising production of the Defiant. Beaverbrook instructed Leonard Lord, to oversee production at Boulton Paul. As part of his rationalisation drive, Lord's staff at Boulton Paul apparently had a lot of the project documentation for the P92 destroyed.

The "Blitz" night-time bombing raids on Britain, that started in the autumn of 1940, gave rise to the issuing of Air Ministry specification F18/40 for a dedicated night-fighter. Significantly, the P92 project was not resurrected at this stage, showing that it was well and truly "dead". Instead, Boulton Paul proposed both a single-engined "Super Defiant" with additional forward-firing cannons (the P97), and a twin-engined, twin-boom design, the P97, that looked a bit like the later American Northrop P-61 "Black Widow". The increasing success of the Beaufighter meant that none of the various designs put forward for F18/40 were adopted.

The Boulton Paul P97. It was designed in a modular form so that it could be put together with a Defiant-style machine gun turret to supplement the forward-firing cannons, or it could have only the forward-firing cannon. Alternatively, a different bottom section with a bomb bay could be fitted so that it could serve as a light bomber. It would seem that by the end of 1940, there was no hope of restarting the P92 project.

Silver Lining

The general manager and chief engineer of Boulton Paul was John Dudley North. The company was very much his "baby". He had single-handedly forced through the creation of the new company at Pendeford after the original Boulton Paul woodworking company of Norwich had wanted to close down their aircraft division in the early 1930s. North was a brilliant mathematician and structural designer. He had a particular interest in aircraft armament, having designed the gun barbettes on the P31 "Bittern" and then the RAF's first fully enclosed turret for the "Overstrand" bomber. After his experience with the turret of the Defiant and then all his research and effort to use the 20mm Hispano cannon in the P88 and P92 there was no one better qualified in gun armament for aircraft in the UK.

The Hispano cannon suffered all sorts of problems when first installed in the Supermarine Spitfire, then the Westland Whirlwind and then the Bristol Beaufighter. Each of the different companies struggled to come up with solutions, but with only limited success. Towards the end of 1940, the Air Ministry asked North to head up a team to try to solve the problems. North had been unaware of the issues the other companies were having with their weapon installations, but he quickly got to grips with the situation, identified the root problems and came up with solutions. It seems he may have anticipated many of the issues when he was designing the P88 and P92. So all the work on the P92 did bear fruit in the end.

After this, the Air Ministry kept North busy until 1944 on a range of structural and armament issues. This prevented him from doing detailed design work for Boulton Paul. Although Boulton Paul did have other designers and continued to put forward designs to Air Ministry specifications, these tenders lacked the technical rigour of North and this may be the reason that no other Boulton Paul aircraft design was put into production until after the war. North was held in such high regard by the Air Ministry that in 1948 they commissioned him to write a 13-volume work called "Design for Reliability".

Boulton Paul's estimates for P92 dimensions and performance of the prototypes.

Note that these vary from those given in the initial tender to the Air Ministry (which are the ones usually quoted in articles).

Note that these vary from those given in the initial tender to the Air Ministry (which are the ones usually quoted in articles).

Length: 55 ft (16.764 metres) Span: 66 ft 3.3 ins (20.2 metres)

Loaded weight: approx 22,000 lb (9980 kg).

Max Speed: 385 mph (620 kph) at 15,000 feet (4572 metres).

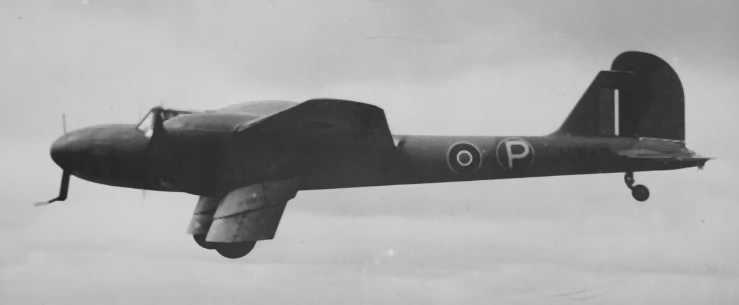

The P92/2, the half-scale P92

The P92/2 was conceived as a flying half-scale replica of the P92, to investigate the aerodynamics of its novel layout. To speed construction, it was to be made of wood and featured a fixed undercarriage with the two main wheels housed in streamlined "trouser" fairings. To better accommodate a normal-sized pilot, the cockpit and nose were made slightly larger and more bulbous in scale than the P92. Small windows were placed on either side of the fuselage, below the main cockpit canopy, to improve the view of the ground. It was to be powered by two 130 hp de Havilland Gipsy Major II engines with fixed-pitch propellers. The engines were to be enclosed in cowlings meant to duplicate the shape of Rolls-Royce Vulture engines as closely as possible. It was initially to be fitted with a fixed, dummy "hump" in place of the turret but it was anticipated that this would be replaced by a working, rotatable replica of the P92 turret to fully investigate the effects on the airflow around the turret as it rotated. To ease concerns that the thin tapered wing might suffer from "tip stall" the wings had slits in them to act as permanent slots. The aircraft was also fitted with an anti-spin parachute, a standard fitting for most British experimental aircraft of the period. The use of flying, smaller-scale replicas had been pioneered by Short Brothers with their S31 half-scale version of the Stirling bomber and the Short Scion Senior which duplicated the layout of the larger Short Flying boats. When originally conceived, it was thought that P92/2 would first take to the air at much the same time as the first proper P92 prototype but that the wooden P92/2 would be more suitable for carrying out experimental changes to investigate airflow than having to make changes to the all-metal P92.

The half-scale P92/2 aircraft in flight. You can see that the cockpit and front fuselage have been made more bulbous than the original P92 to better accommodate the pilot. The "P in a circle" insignia for a prototype aircraft was adopted in June 1942.

As a pioneer of metal construction, Boulton Paul had dispensed with the ability to construct wooden aircraft. So the building of the P92 was contracted out to the Heston aircraft company on the outskirts of London (Heston was a company that specialised in wooden construction, their most famous aircraft being the beautiful Heston Phoenix five-seat monoplane). A contract to build the P92/2 was given to Heston sometime in 1939 and the serial number V3142 was allocated to the aircraft. Heston allocated their own type number to the project: The Heston JA.8.

Just why the P92/2 survived the cancellation of the P92 project is a mystery. Perhaps it was just too far advanced to warrant stopping construction. It first took to the air sometime in early 1941 and had been delivered to Boulton Paul's airfield near Wolverhampton by May 1941. The next mystery is, just what did it do for the next two years? The planned rotating turret was never fitted and although a series of tests with pressure sensors and wool tufts on the wing and dummy turret were conducted, this can hardly have filled the two-year period. The one thing that does seem to have been looked into was the effect of sealing the slots in the wings closed. This was reported to not result in dangerous stalling characteristics (confirming Boulton Paul's suspicions that such slots were not required on the P92).

The neat little Boulton Paul P92/2 (Heston JA.8), photographed in a bucolic setting at the Boulton Paul airfield and factory complex at Pendeford, near Wolverhampton. It is on the "compass-swinging circle", which would place it just east of where the current Gargill Meats building stands.

Some articles suggest that the cockpit of the P92/2 was so cramped that only a very small pilot could be accommodated. The cockpit was certainly narrower than normal, with floor depth limited so that the pilot had to use a "back" parachute rather than the more usual "cushion" type. The engine instruments had to be mounted on the side of the engine cowlings because of a lack of space on the instrument panel (this was by no means unique to the P92/2, a large number of 1930s twin-engined aircraft had them mounted like that). However, the Boulton Paul test pilot who did most of the flying of the P92/2, Flt Lt Cecil Feather, was actually a very large man. He had difficulty reaching the handle that ejected a hatch on the port side of the cockpit for parachute exit, so a piece of string had to be run from the handle and taped to the side of the cockpit for him to pull in an emergency. Then he would have collapsed the seat back and rolled to the side and backwards out of the hatch to avoid the nearby propeller. The cockpit canopy was a one-piece unit that had to be fitted into place after the pilot was inside. Because of the nearness of the propellers this had to be done before the engines were started and the canopy would only be removed once the engines were stopped (the pilot could eject the whole canopy to escape in the event of a crash-landing).

The P92/2 in flight. It had a camouflage scheme of dark earth (brown) and dark green on the upper surfaces and fuselage sides with yellow undersurfaces.

After being at Boulton Paul for two years the P92/2 was sent for evaluation by A&AEE at Boscombe Down in July 1943. Their report was naturally critical of the narrow cockpit, the lack of view to the sides and rear and the "bit of string" escape method. It was suggested that jettisoning the complete canopy would be a better means of escape, accepting the risk that it might foul one of the propellers in the process. However, the flying qualities were judged to be excellent. One issue experienced was airframe vibration caused by the main undercarriage wheels turning in flight, either after takeoff or after a steep dive. This could be stopped by applying the wheel brakes. A greater range of elevator trimmer control was also deemed to be desirable for low-speed handling and it was felt that a bigger area of flap might be desirable. The opportunity was then taken to investigate the change in handling at the stall with the wing slots taped over. This confirmed Boulton Paul's findings that they were not strictly necessary although it was felt that leaving them unsealed might be an advantage to avoid a stall if the aircraft bounced into the air after a bad landing. If you want to read a precis of the full A&AEE report on the P92/2 it can be found in Tony Buttler's "British Experimental Combat Aircraft of World War II" and also in Philip Jarrett's 1990 article in Aeroplane Monthly magazine (see sources below).

After testing by A&AEE, the P92/2 was returned to Boulton Paul, where, despite the limitations of its cramped cockpit, it was used as a company "hack" aircraft for running errands and communications duties, usually being flown by Flt Lt Feather. It remained on the "secret list" for the rest of the war. When "Jane's All the World's Aircraft" was published in 1945, only a tentative suggestion of an "experimental aircraft" was mentioned under the headings for both Boulton Paul and Heston Aircraft. When Feather left flying duties in 1945, the P92/2 was stripped of its engines and stored in a shed at Boulton Paul's airfield. It was reported to have been burnt as part of a bonfire night party in the early 1950s.

P92/2 Specification

Wingspan: 33ft 1.5 inches (10.0965 metres) Length: 27ft 6 inches (8.382 metres) Height: 7 ft 7 inches (2.3114 metres)

Wing Area: 177 Sq feet (16.444 Sq metres). All-up weight: 2,776 lb (1,260 kg).

Max Speed: 152 mph (245 kph). Cruising Speed: 135 mph (217 kph).

Stalling Speed: Flaps up - 59mph (95 kph). Flaps down: 50 mph (80 kph).

What If?

Painted as if they had got into service. Boulton Paul P92s with Sabre engines engage Junkers Ju 89 bombers using "Attack Plan B" for turret fighters; firing from in front of and to the side to avoid return fire ("Attack Plan A" was a no-allowance attack from behind and below). Meanwhile Typhoon fighters are approaching from the rear to execute "Attack Plan 3" for single-seat fighters.²

Painted as if they had got into service. Boulton Paul P92s with Sabre engines engage Junkers Ju 89 bombers using "Attack Plan B" for turret fighters; firing from in front of and to the side to avoid return fire ("Attack Plan A" was a no-allowance attack from behind and below). Meanwhile Typhoon fighters are approaching from the rear to execute "Attack Plan 3" for single-seat fighters.²

Boulton Paul P92 with Vulture engine, painted as if it had gone into service, in this case attacking a Heinkel He177. I did this painting based on the 3-view drawings of the project in its early stages. Since then Les Whitehouse has written a book giving updated diagrams of the P92 in its final stage of development. Image © John Dell

If Beverbrook's purge of aircraft projects had not taken place in 1940 then it is probable that the development of the P92 would have continued. However, the protracted development problems of both the Vulture and Sabre engines would have delayed the project considerably. The Vulture was abandoned and the Sabre only saw service from the middle of the war, and its reliability was woeful for the first year after its introduction. Even then, supplies of Sabres for the P92 would have been low, because priority would almost certainly have been given to the Hawker Typhoon fighter. But it's possible to imagine numbers of the P92 being available in the early months of 1944 to be used as night fighters (presumably with airborne radar fitted) to combat Operation Steinbock, the German's "Little Blitz" on Britain.

In such a scenario (of Beverbrook's purge not taking place) it's likely that the Boulton Paul cannon turret would have first seen combat mounted on the Bristol Type 159 bomber, in an attempt to return to daylight raids on Germany. The Type 159 was to be powered by Bristol Hercules engines. Although it was ordered later, the Type 159 was much closer to production than the Boulton Paul P92 when work on both projects was ordered halted in May 1940.

A Boulton Paul cannon turret mounted on a Bristol Type 159 "Beaubomber", imagined in an encounter with Bf109 fighters over the coast of Europe. Image © John Del

Notes

¹ When the Germans initially began rearming, the Luftwaffe was close to adopting a policy of strategic bombing similar to that of the British. Generalleutnant Walter Wever, Chief of the German Air Staff, was a particular advocate of long-range four-engined bombers; he ordered the construction of the huge Dornier Do19 and Junkers Ju89, the latter of which was to be armed with defensive cannons. The death of Weaver in an air crash in 1936 prompted a switch in policy to more easily produced, twin-engined designs with less range. Another German advocate of strategic bombing and "battleplane" big bomber designs was the commander of the air war academy in Berlin, Generalleutnant Dr Robert Knauss. In 1932, he caused a minor sensation in Britain with the publication of his book "War in the Air" (original German title "Luftkrieg 1936") a fictionalised story about a clash between Britain and France in which Paris is destroyed with bombs and poison gas by a force of large bombers. There was no doubt that the highly militarised Britain that Knauss described was meant to represent a rearmed Germany.

² To find out more about the RAF's "Fighter Attack Plans", I recommend reading "Battle Tactics" a chapter written by the British ace "Johnnie" Johnson for the 1990 Salamander book "The Battle of Britain -The Greatest Battle in the History of Air Warfare", edited by Richard Townshend Bickers. It has some wonderful diagrams of how the Attack Plans were supposed to work. Diagrams of the "Attack Plans" for the Defiant turret fighter can be found in the article "The Defiant's Rationale" by Dr Alfred Price in the October 2008 edition of "Aeroplane" magazine. It is also worth reading for its outline of a 1940 document from A&AEE that justified the turret-fighter concept.

³ The French used the 20 mm cannon with 60-round magazines in various mountings on bomber aircraft. They evolved a mounting with a pair of machine guns alongside the cannon so that the gunner still had something to fire with when the cannon ammunition ran out.

² To find out more about the RAF's "Fighter Attack Plans", I recommend reading "Battle Tactics" a chapter written by the British ace "Johnnie" Johnson for the 1990 Salamander book "The Battle of Britain -The Greatest Battle in the History of Air Warfare", edited by Richard Townshend Bickers. It has some wonderful diagrams of how the Attack Plans were supposed to work. Diagrams of the "Attack Plans" for the Defiant turret fighter can be found in the article "The Defiant's Rationale" by Dr Alfred Price in the October 2008 edition of "Aeroplane" magazine. It is also worth reading for its outline of a 1940 document from A&AEE that justified the turret-fighter concept.

³ The French used the 20 mm cannon with 60-round magazines in various mountings on bomber aircraft. They evolved a mounting with a pair of machine guns alongside the cannon so that the gunner still had something to fire with when the cannon ammunition ran out.

LINKS

Nevington War Museum article on the Boulton Paul P92/2

Sources - in reverse chronological order of publishing.

"Boulton Paul 1917-1961- Aircraft, Projects and Studies" by Les Whitehouse, published by Crecy in 2021, ISBN: 9781910809488. An outstanding, large format book with no less than 9 pages devoted to the P92 and P92A, with the best diagrams and photos available. The text is closely packed so there is a lot of information. Currently this is the only book you'll find diagrams of the P92 project in its revised form, prior to cancellation. The revised dimensions quoted on this webpage are from this book.

"British Experimental Combat Aircraft of World War II" By Tony Buttler, published by Hikoki in 2012. ISBN: 9 781902 109244. This large-format book has no less than 7 pages about the P92 and P92/2. It has lots of photographs of the P92/2 from different angles. The text is quite widely spaced.

"British Secret Projects Fighters and Bombers 1935-1950" by Tony Butler, published by Midland Publishing in 2004. ISBN: 1 85780 179 2. It has about half a page about the P92 and another two and a half pages about the other contenders for the F.11/37 specification. It also covers the various bomber and flying boat designs with 4-cannon turrets for the B.1/39 and R.5/39 specifications.

"The Turret Fighters" by Alec Brew, published by the Crowood Press in 2002, ISBN: 1 86126 497 6. This has four pages about the P92 and another 3 pages about the P92/2.

"Britain's Shield - Radar and the Defeat of the Luftwaffe" by David Zimmerman, published in 2001 by Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509 1799 7. This book has no information about the P92 directly, however, it details Frederick Lindermann's attempts to push through his idea of dropping bomblets onto enemy bomber formations.

Some details of the testing and form of the "scatter" bomblets tested by A&AEE are detailed in the "Out of the Archives" article in the second (Summer) 1998 edition of Air-Britain "Aeromilitaria" magazine.

"Boulton Paul Aircraft Since 1915" by Alec Brew, published in 1993 by Putnam. ISBN:0 85177 860 7. It has seven and a half pages about the P92 and P92/2. This book is now somewhat dated and the information about the P92 is not entirely correct.

"Boulton Paul Aircraft" compiled by the Boulton Paul Association, published by the Chalford Publishing Company in 1996 as part of their "Archive Photograph" series. ISBN 0 7524 0625 6. It does not have any information on the P92, but it does shed light on the Boulton Paul company as a whole.

"The British Aircraft Specification File" by KJ Meekoms and EB Morgan, published by Air Britain in 1994 (ISBN 0 85130 220 3). It outlines Air Ministry specification F.11/37 that the P92 was designed to meet.

A 4-page article on the P92 and P92/2 by Philip Jarrett in his "Nothing Ventured" series in the November 1990 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine.

The 1968 obituary to John Dudley North in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (available as a PDF at <this link> ), does not give any detail on the P92, but it does show the ends J D North went to to ensure the reliability and effectiveness of his turret designs.

"Bristol Type 159 (B.1/39)" an article by Phil Butler in the winter 2009 (Vol 35, issue 140) edition of Air-Britain Aeromilitaria magazine gives details of the Bristol Type 159 "Beaubomber" and gives a short description of the turret types ordered for it.

Nevington War Museum article on the Boulton Paul P92/2

Sources - in reverse chronological order of publishing.

"Boulton Paul 1917-1961- Aircraft, Projects and Studies" by Les Whitehouse, published by Crecy in 2021, ISBN: 9781910809488. An outstanding, large format book with no less than 9 pages devoted to the P92 and P92A, with the best diagrams and photos available. The text is closely packed so there is a lot of information. Currently this is the only book you'll find diagrams of the P92 project in its revised form, prior to cancellation. The revised dimensions quoted on this webpage are from this book.

"British Experimental Combat Aircraft of World War II" By Tony Buttler, published by Hikoki in 2012. ISBN: 9 781902 109244. This large-format book has no less than 7 pages about the P92 and P92/2. It has lots of photographs of the P92/2 from different angles. The text is quite widely spaced.

"British Secret Projects Fighters and Bombers 1935-1950" by Tony Butler, published by Midland Publishing in 2004. ISBN: 1 85780 179 2. It has about half a page about the P92 and another two and a half pages about the other contenders for the F.11/37 specification. It also covers the various bomber and flying boat designs with 4-cannon turrets for the B.1/39 and R.5/39 specifications.

"The Turret Fighters" by Alec Brew, published by the Crowood Press in 2002, ISBN: 1 86126 497 6. This has four pages about the P92 and another 3 pages about the P92/2.

"Britain's Shield - Radar and the Defeat of the Luftwaffe" by David Zimmerman, published in 2001 by Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509 1799 7. This book has no information about the P92 directly, however, it details Frederick Lindermann's attempts to push through his idea of dropping bomblets onto enemy bomber formations.

Some details of the testing and form of the "scatter" bomblets tested by A&AEE are detailed in the "Out of the Archives" article in the second (Summer) 1998 edition of Air-Britain "Aeromilitaria" magazine.

"Boulton Paul Aircraft Since 1915" by Alec Brew, published in 1993 by Putnam. ISBN:0 85177 860 7. It has seven and a half pages about the P92 and P92/2. This book is now somewhat dated and the information about the P92 is not entirely correct.

"Boulton Paul Aircraft" compiled by the Boulton Paul Association, published by the Chalford Publishing Company in 1996 as part of their "Archive Photograph" series. ISBN 0 7524 0625 6. It does not have any information on the P92, but it does shed light on the Boulton Paul company as a whole.

"The British Aircraft Specification File" by KJ Meekoms and EB Morgan, published by Air Britain in 1994 (ISBN 0 85130 220 3). It outlines Air Ministry specification F.11/37 that the P92 was designed to meet.

A 4-page article on the P92 and P92/2 by Philip Jarrett in his "Nothing Ventured" series in the November 1990 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine.

The 1968 obituary to John Dudley North in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (available as a PDF at <this link> ), does not give any detail on the P92, but it does show the ends J D North went to to ensure the reliability and effectiveness of his turret designs.

"Bristol Type 159 (B.1/39)" an article by Phil Butler in the winter 2009 (Vol 35, issue 140) edition of Air-Britain Aeromilitaria magazine gives details of the Bristol Type 159 "Beaubomber" and gives a short description of the turret types ordered for it.