Dinger's Aviation Pages

Armstrong Whitworth Ensign

Britain's 40 seat behemoth transport (updated with new and revised information October 2025).

Britain's 40 seat behemoth transport (updated with new and revised information October 2025).

One of Britain's forgotten aircraft of World War Two, it was the largest British landplane when it first flew.

Press advert for the Ensign, showing its curious nose-down flying attitude. A characteristic shared with Armstrong Whitworth's Whitley bomber.

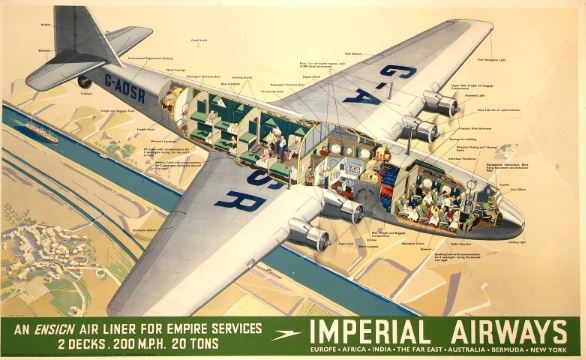

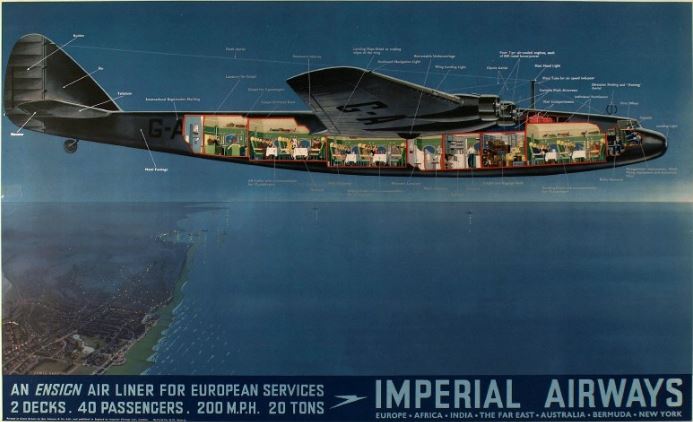

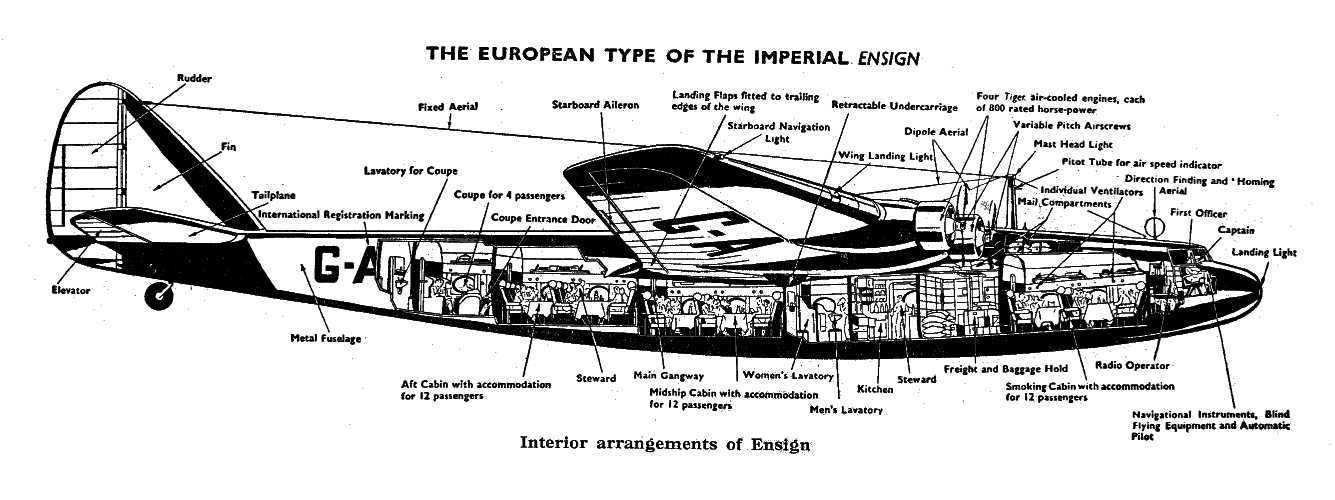

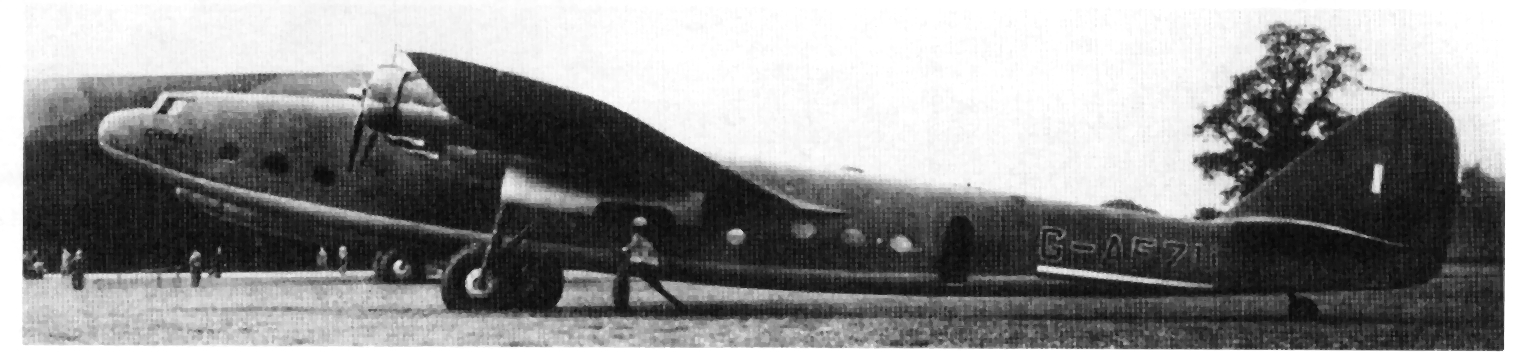

The AW type 27 Ensign was designed by Armstrong Whitworth who had their main factory complex in Coventry in the heart of England. They had built a reputation for safe and reliable, if not exactly ground-breaking airliners with their three-engined Argosy biplane and the much-sleeker AW15 Atalanta four-engined monoplane. Imperial Airways wanted a fleet of big, four-engined landplanes to supplement their flying boats on "Empire" routes to the Far East and Africa, but also operate European routes with a greater capacity. So was born the Ensign, able to carry 20 passengers in an overnight sleeper arrangement on Empire routes or 40 passengers (in remarkable leg-stretching comfort by modern standards) on shorter routes. This order was placed in 1934, at a transitional time in aircraft design. The new stressed-skin monocoque monoplane designs of airliners were just coming out of the USA. The Ensign featured many of the new design features pioneered in American airliners. It was a streamlined monoplane with a largely monocoque fuselage. It had a retracting undercarriage, then still very much a novelty. It also had flaps to cut down its landing speed. However, it had a fabric covering on the wing aft of the main spa, and the fin and control surfaces were also fabric-covered; something that would begin to look anachronistic within a few years. The Ensign differed from most US airliners of the period in having the wing mounted on top of the fuselage. This meant the retracting undercarriage was a huge affair. However, it gave the passengers an unobstructed view of the ground (the scenic aspect of aircraft flight was then seen as an important selling point against trains and ocean liners) and made loading and unloading the aircraft via the rear doors possible without high air-stairs. This high-wing configuration was apparently specified by Imperial Airways in preference to Armstrong Whitworth's original design which featured a low wing. Interestingly, at the same time, Armstrong Whitworth were chasing orders from Czechoslovakia and Belgium for their AW-30 project, a low-wing, twin-engined, transport/bomber design that looked very much like the American Douglas DC-2 (the AW-30 was never built). A price of £37,000 for each Ensign was agreed (equivalent to about two and a quarter million pounds in 2025).

The first Ensign G-ADSR is towed out by hand. Note how large the passenger windows are.

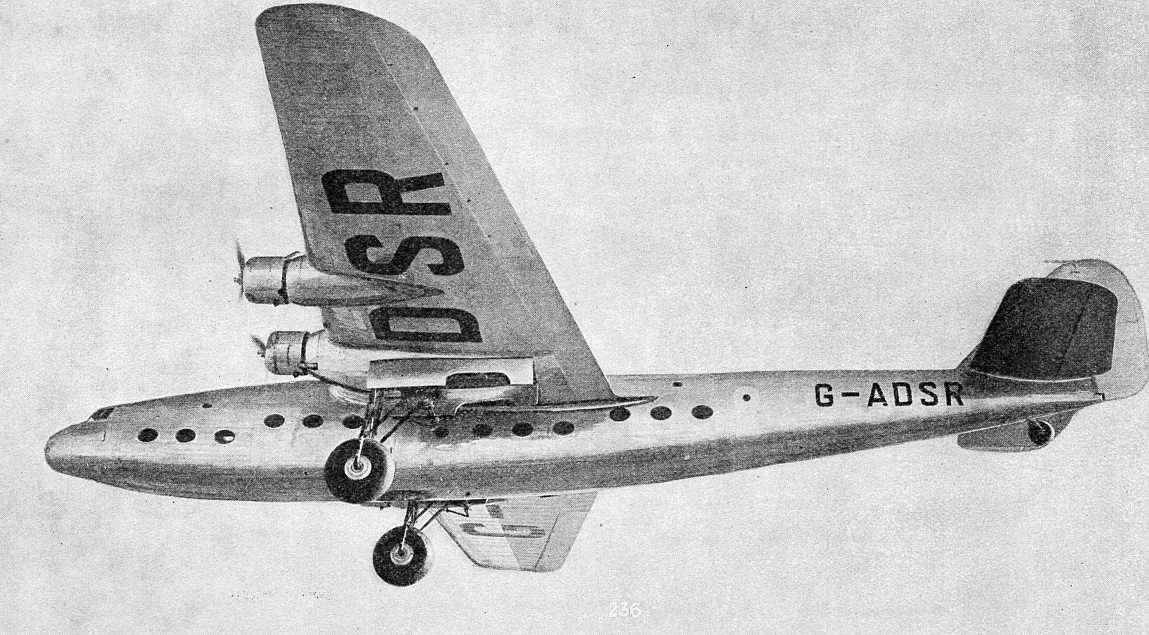

G-ADSR in flight. The wing was thick enough to allow a crawl space out to the rear of the engines for inspection.

Inside the Ensign's forward cabin. The Ensign's interior and upholstery were finished in the colours green and cream.

Ensign in Imperial Airways "Empire Route" Sleeper mode.

Ensign in "European Capital" 40-seat mode.

Perhaps the decision that affected the long-term career of the Ensign most was where to build these mighty beasts? The obvious choice would have been Armstrong Whitworth's main plant at Coventry, with its airfield at Baginton. However, the existing facilities at Coventry were already committed to the production of Whitley bombers for the RAF. Instead, production of the Ensign was shoehorned into two old hangars at Hamble, on the Solent estuary near Southampton. A site owned by the larger Hawker-Siddeley group of which Armstrong Whitworth was a part. Here production could take place on two Ensigns at a time. The major subassemblies were built and laid out in one hangar before being moved to the other for final assembly. When finished, each Ensign had to be taken over a public road to the grass airfield from which their maiden flight would be made. The first Ensign (G-ADSR) first flew on 24th Jan 1938. This date was a big disappointment to Imperial Airways. When they ordered the AW27 in September 1934, it had been expected that the first one would fly in 1936, so the whole programme was running nearly two years behind schedule. Testing of the first Ensign had some issues; on the first flight, the rudder was found to be over-balanced. The co-pilot, Eric Greenwood, had to brace himself in his seat to keep the rudder in a central position, while the chief pilot, C.K. Turner-Hughes, handled all the other controls. On a later test flight, all four engines stopped and the huge aircraft was very lucky to make a dead-stick landing at RAF Bicester. It was found that the fuel supply had been cut off due to the misleading way the fuel controls had been labelled (the controls were located in the central cabin out of reach of the pilots in the cockpit). Another issue that dogged the test flights was that the elevators would lock up at altitude; this was found to be caused by the huge aircraft shrinking by an appreciable amount in low temperatures, causing the control wires to sag and snag against each other. This was cured by rerouting the control wires and adding tensioners.

The prototype Ensign, G-ADSR.

The first Ensign went for testing at the Aeroplane & Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at Martlesham Heath in June 1938. While it was being tested it suffered a string of small failures. The flying qualities were rated to be generally good, although it was judged to be underpowered, with a poor rate of climb and it could not maintain height with two engines throttled back. There were also numerous ergonomic issues. Reluctantly, A&AEE felt unable to give the Ensign a Certificate of Airworthiness (C of A). The Ensign returned to A&AEE the following month with larger diameter propellers fitted and some of the requested modifications done. The improvement in performance with the new propellers was enough to warrant issuing a C of A providing the rest of the requested changes were carried out. On the 20th of August 1938, two pilots from A&AEE travelled to Armstong Whitworth's airfield at Bagington to check the Ensign, but still found issues. On the 10th of September 1938, another A&AEE pilot travelled to Bagington and this time the improvements were good enough to secure the issuing of a C of A, meaning it could start airline service.

G-ADSR in flight.

Armstrong Whitworth Ensign pictured with an Armstrong Siddeley Saloon Car. From 1935, both Armstrong Whitworth and Armstrong Siddeley were subsidiaries of the Hawker Siddeley group. Notice the difference in the number of porthole windows between the port and starboard sides of the aircraft.

Another view of G-ADSR

The setup at Hamble precluded any sort of mass production of the Ensign. It seems that from the start it was anticipated that only the order for 12 of the type for Imperial Airways would ever be built and the whole project was costed on this basis (a fair assumption considering that AW's previous airliners had only ever been sold to Imperial Airways). A delivery rate of one aircraft per month was stipulated by Imperial Airways.

An Armstrong Whitworth van blocks the way while G-ADSS Egegia, the second Ensign built, is moved across the public road at Hamble for its first flight.

The low rear of the Ensign allowed passengers to alight with only a small set of steps (most able-bodied people could have simply jumped on or off the Ensign). Note the huge undercarriage and the enormous main tyres, the largest aircraft tyres produced in the UK up until that time.

The Ensign featured in a contemporary poster for Dunlop Tyres.

A busy day at Croydon airport in 1939. In the foreground is Ensign G-ADSX Ettrick, while in the background is G-ADSS Egeria. On the right are two of the equally-new de Havilland Albatross airliners while on the left is an old HP-42 biplane airliner. In the middle, looking quite small, is a 4-engined de Havilland DH86.

The large rudder of Ensign G-ADSR.

Armstong Whitworth always tried to use the engines built by their sister company, Armstrong Siddeley, in their designs. So it was natural that the Ensigns had Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX engines of 810 horsepower, a medium-supercharged engine made to a military specification, but initial reliability was woeful (as it also was on the Blackburn Shark torpedo-bombers and early Whitley bombers which also used the type). An attempt by three Ensigns to get the Christmas mail to Australia in 1938 ended up with all three aircraft failing to reach their destination. Two of the Ensigns suffered engine failures while the third had an undercarriage failure which led to it having to fly back to the UK with its wheels extended. Alarmed by this unreliability, Imperial Airways returned all its fleet (by then numbering five) to Armstrong Whitworth for rectification. This involved replacing the Tiger IX engines with a modified version called the Tiger IXC (the "C" stood for civil) which were reported to give better reliability and increased power for short periods for take off, albeit with very slightly less power for cruising (805 horsepower)¹. This mark of the engine was made specifically for the Ensign. At the same time, the Ensigns were fitted with constant-speed propellers and it was probably this that improved reliability and performance more than the new engines. There were also refinements to the rudder, ailerons and control cable runs that made the aircraft lighter on the controls. G-ADSW Eddystone went to A&AEE in May of 1939 to have these modifications tested. While testing was successful, with a welcome increase in the rate of climb, the pilots at Martlesham Heath noted that the flying qualities of G-ADSW Eddystone were quite different to G-ADSR Ensign they had tested the previous year. It became obvious that the slight differences in construction of these giant aircraft meant that each aircraft had its own particular handling qualities. Some were better harmonised and lighter on the controls than others.

Ensigns in their pre-war Imperial Airways livery.

Ensign G-ADSX Ettrick in flight.

Ensign G-ADSX Ettrick in flight.

After these modifications, the growing fleet of Ensigns started to settle down to earn their keep. They were used by Imperial Airways on their European routes. The plan to use them for the leg of the "Empire route" across India in association with Indian Trans-Continental Airways never came to fruition (Indian serial numbers were allocated to some of the Ensigns). This was because the Ensigns were deemed to be somewhat underpowered and struggled to cope with the "hot-and-high" conditions encountered on the sub-continent. In service, the Ensign was famed for its short-field performance. Despite its size, it was quite happy landing on quite small grass airstrips; landing into a 5.5 mph (8.85 kph) headwind could be done in only 280 yards (256 metres). However on take-off, once airborne it was very slow to climb, due to the drag of its massive undercarriage which took an extraordinarily long time to retract, some 70 to 90 seconds. In the event of a loss of hydraulic power to extend the undercarriage it could be extended manually by cranks, but the process took an astonishing 20 minutes!

The Ensign's original AW Tiger engine above that enormous undercarriage.

Loading air-mail onto G-ADSU Euterpe. Apparently, she was known affectionately as "You Twerp!". This was the aircraft that came to grief on Bonniksen's Airfield. Note the large radio aerial mast and the radio direction finding (DF) loop mounted above the cabin.

A lineup of Ensigns.

A lineup of Ensigns.

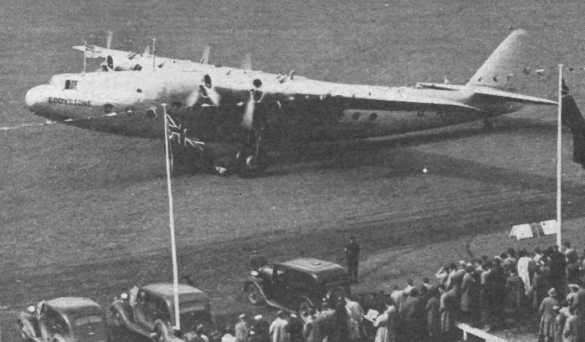

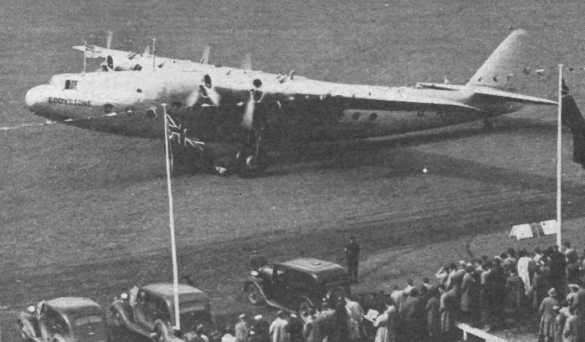

The Ensign G-ADSW Eddystone put in an appearance at the inauguration of Birmingham's Elmdon airport on the 8th July 1939.

Ensign G-ADSS Egeria with crude camouflage applied to just the upper surfaces of the wings and tailplane along with the top of the fuselage.

Ensign G-ADSS Egeria with crude camouflage applied to just the upper surfaces of the wings and tailplane along with the top of the fuselage.

With the outbreak of war, the Ensigns were at first crudely camouflaged (it would seem one joker went so far as to paint a flock of sheep on the huge wings of one!) and operated by the National Air Communications service. They helped fly out the groundcrews of RAF squadrons to France in the first weeks of the war, with the first such flight taking place on the 2nd of September 1939, the day before the formal declaration of war. Then the Ensigns were used to provide a twice-daily service to Paris and also carried out supply flights for the RAF and Army. Some Ensigns seem to have been operated by, or under the control of, number 24 Squadron of the RAF. The Ensigns gave valuable service through the severe winter of 1939/40. On December 15th 1939 the fleet had its first casualty when G-ADSU Euterpe, on a flight from Whitchurch (Bristol) to Doncaster, tried to land to avoid an approaching weather front and overshot the tiny landing ground called Bonniksen's airfield (owned by Major Julius Bonniksen) near Leamington Spa in Warwickshire.² It seems this tiny airfield was just too small for even the Ensign's renowned short-field performance, particularly as the pilot assumed the road and ditch he ended up in was a "painted on" camouflage feature. The aircraft was returned to Hamble by road in March of the following year. It's hard to imagine the huge airframe being manoeuvred down the narrow twisting roads of pre-motorway Britain!

G-ADSU Euterpe being recovered from the road (Harbury Lane) alongside Bonniksen's Airfield. Note the strange, hastily applied, camouflage pattern. At the start of WW2, most British airfields were camouflaged with lines of chalk dust across them to resemble roads and black tar to resemble hedges. The pilot of Euterpe, Captain F.R. Garside, had mistaken Harbury Lane for one of these camouflage features.

The crashed G-ADSU Euterpe, viewed from the other side. Recovery must have been a cold and difficult process, because the winter of 1939/40 was particularly harsh.

The crashed G-ADSU Euterpe, viewed from the other side. Recovery must have been a cold and difficult process, because the winter of 1939/40 was particularly harsh.

When the war began, the Germans started dropping their new magnetic mines in the approaches to Britain's harbours. One solution to the problem was to fit an aircraft with a large annular structure with wire wound around it through which an electric current would be passed. When such an aircraft flew low over the sea it would "fool" the magnetic mine into thinking a ship had passed overhead and detonate it. It was planned to convert the Ensign fleet to this task and wind-tunnel tests of a model Ensign with the ring were conducted. The equipment was developed by Barnes Wallis at Vickers and it was eventually decided to use Vickers' own product, the Wellington bomber, as the carrier for the equipment. So the Ensigns narrowly missed having to spend their life as "mine-sweepers". ³

G-ADSV Explorer in wartime camouflage. Note the fuselage serial number underlined with a red, white and blue stripe.

When the Germans invaded Norway in April 1940, apparently an Ensign (G-ADST Elsinore) was selected for a one-way mission to crash-land on a frozen lake to deliver Royal Engineers and a load of explosives to blow up the railway between Andalsnes and Dombas to slow up the German advance. Bad weather delayed the mission and it was cancelled when it was found that the Germans had already overrun the landing site. ⁴

Ensigns and a Spitfire, pictured early in the war.

When the blitzkrieg broke on the Western Front, in May 1940, the Ensigns came into their own, flying daring missions to recover personnel from France. It was now that the Ensign's short take-off and landing ability came to the fore. On 21st May, one Ensign was among a number of aircraft that took groundcrew to recover Hurricane fighters abandoned on Merville aerodrome, in the path of the German advance. The mission was headed by Louis Strange (although Strange himself flew out in a DH Dragon). From descriptions of these operations, it seems the Ensigns involved were stripped of all interior fittings (seats etc) to allow the maximum flexibility in carrying equipment. Passengers had to sit on the floor.

Ensign G-ADSX Ettrick pictured early in the war. Ettrick was destroyed after a bombing raid at Le Bourget airport.

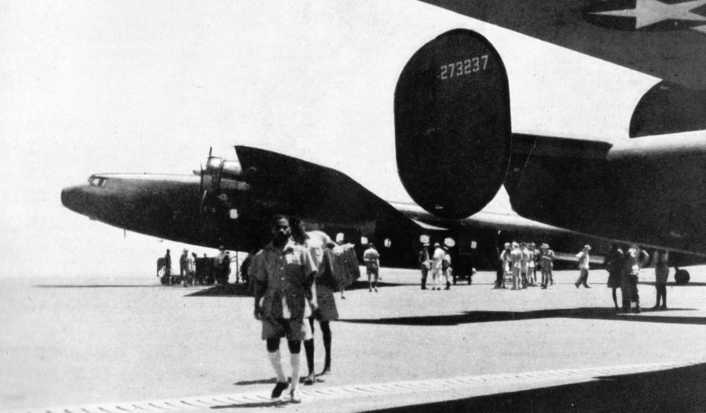

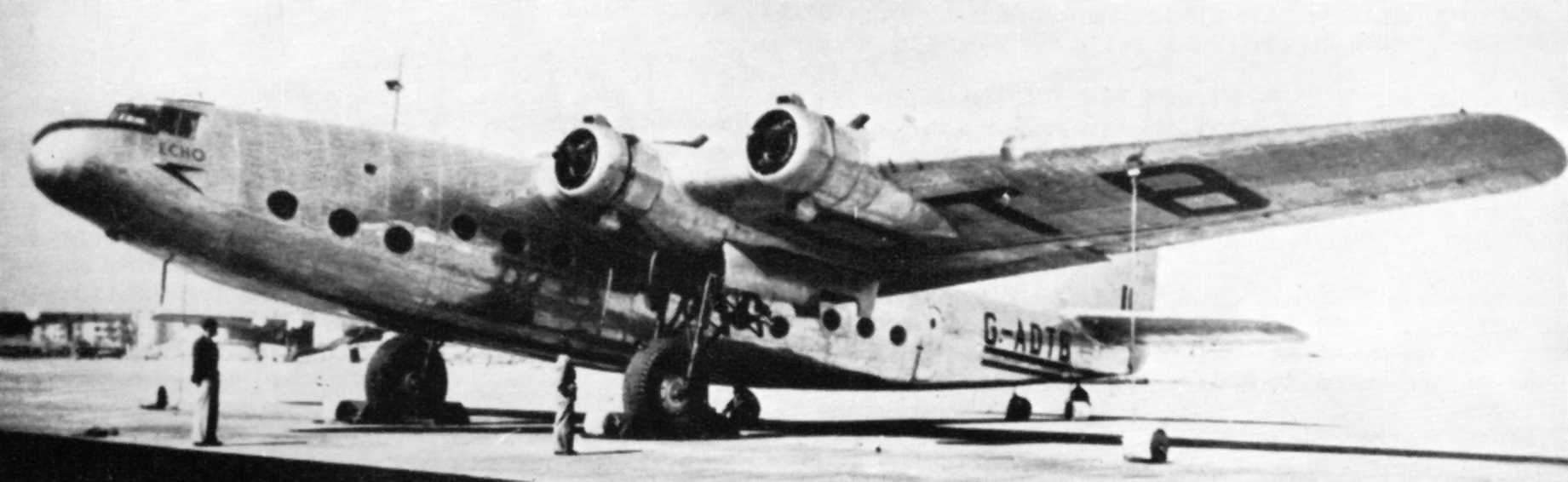

But the Ensign fleet took losses. On the 23rd of May, five Ensigns returned to Merville aerodrome to try to fly in desperately needed anti-tank ammunition in company with Siai Marchetti S 73 airliners of the Belgian airline Sabena that had taken refuge in Britain. During unloading, the airfield was attacked by Messerschmitt Bf109s. One of the S73s (registration OO-AGZ) and Ensign G-ADSZ Elysian were destroyed by strafing. Returning to England another Belgian S73 (OO-AGS) was shot down, Ensign G-ADTB Echo had its rudder peppered by enemy fire, while Ensign G-ADTA Euryalus had two engines disabled and had to crash-land at Lympne airfield in Kent.⁵ Euryalus was recovered by road to Hamble where she was broken up to provide parts to repair Euterpe the following year.

The burnt-out wreck of G-ADSZ Elysian after it had been destroyed by strafing Bf109 fighters at Merville. Notice the French-style rudder stripes.

One amazing mission, which illustrates the chaotic conditions during the retreat to Dunkirk, was flown by an Ensign piloted by Flt Lt Henry Bernard Collins (an ex-Imperial Airways Captain who later went on to be a pilot for Winston Churchill) with Flying Officer Earl Bateman Fielden acting as copilot. On the 25th of May 1940, they were tasked with flying in another load of desperately needed anti-tank ammunition (63 boxes) along with 25 boxes of "25-pounder" ammunition to the British forces now surrounded in Northern France. The initial plan was to parachute these into an airfield at Seclin at night. The pilots rightly complained that this would be virtually impossible due to the small rear door of the Ensign and because only parachutes with rip-cords were available. They decided to attempt to land at Seclin instead, setting off from Croydon aerodrome at 2.20 GMT on the 26th May. Unfortunately, the radio operator they were allocated was not familiar with the radio equipment on the Ensign, so they were out of radio communication for the duration of their mission. On the flight out to France, they had to avoid an unexpected balloon barrage over the coastal town of Deal, and then encountered increasing "friendly fire" from anti-aircraft guns over France. This anti-aircraft fire became so intense that they had no option but to land in a potato field south-west of Armentières. Fortuitously,the field was next to a British Army radio detachment, who were able to arrange the speedy pick-up of the ammunition which went on to be used against the German advance. The risk of friendly fire during the day was judged to be so high that it was decided not to attempt to fly back in daylight. The Ensign was hidden during the day with camouflage netting that had fortuitously been put aboard the aircraft before the flight. It was discovered that Seclin, the airfield they had been expecting to land at, was already under German control. Meanwhile, the British headquarters in France had been expecting them to land at a different airfield entirely, at Lille Marcq-en-Baroeul, and a party of high-ranking RAF officers had been waiting to be picked up from there. The RAF officers were quickly directed to the Ensign's new location. It took off at 2.15 GMT on the 27th May with the party of RAF officers and an Army Brigadier, together with 550 lbs (250 kg) of mail. The take-off at night was guided by two hurricane lamps and the headlights of the RAF officers' abandoned Chevrolet car. The Ensign had to fly back to Britain with its undercarriage extended because of a failure of the hydraulic system. It landed at Manston first, before proceeding back to Hendon. For his leadership during the mission, Flt Lt Henry Bernard Collins was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).⁶

On the 1st of June, G-ADSX Ettrick was damaged by a bombing raid while on the ground at Le Bourget airport near Paris and had to be abandoned; photos show it was later completely destroyed (despite reports to the contrary it was never repaired and used by the Germans).⁹ One Ensign called into Bordeaux airfield to refuel after carrying diplomatic passengers to Lisbon, only to discover that France had capitulated, the crew loaded aboard a party of RAF personnel who were stranded there and got them back to the UK.

It is evident that the ad-hoc employment of these giant aircraft created a bit of resentment and it was felt that a more organised use of them could have saved more people and equipment from capture by the Germans. An anonymous Army officer wrote bitterly in his diary, " A good example of the chaos is the despatch in error of No 24 Communication Squadron. This squadron left yesterday without passengers. The squadron could have carried back 800 men. They took none. One officer returned home in a large 30-seater aircraft alone." ⁷

During the Battle of Britain, the Ensigns were often used to help move Fighter Command squadrons around the UK. Exhausted and depleted units would be withdrawn from the south and rested squadrons would be flown in from the west and north. A single Ensign could carry all the ground servicing personnel of a squadron in one go. Again, its short-field performance was a big help during this period, able to land on the smallest, and often bomb-cratered, airfields.

In November 1940, a German bombing raid on Whitchurch airfield (near Bristol) destroyed Ensign G-ADTC Endymion and slightly damaged Explorer, Echo and Empyrean. The three damaged Ensigns were quickly repaired. With the drawing to a close of the Battle of Britain, the Ensign fleet settled down to providing regular services throughout the UK. In particular, they were used on the route to Foynes in the Republic of Ireland to meet up with the Boeing Clipper flying boats from the USA.

Ensign G-ADSR in wartime camouflage colours.

When Britain went to war in 1939, production of almost all transport aircraft by British industry stopped (a small production run of 16 DH Flamingo twin-engined aircraft was allowed to continue into early 1941). The Air Ministry thought the war would be decided in a matter of months by massive bombing raids by both sides. So all resources were thrown into supplying bombers, fighters and the training aircraft needed to prepare their crews. They simply did not appreciate that a global war was going to need hundreds, if not thousands, of transport aircraft. So production of the DH Albatross and Flamingo airliners was cut short, and even production of the Bristol Bombay bomber/transport was curtailed. Armstrong Whitworth had received a follow-on order for two more Ensigns for Imperial Airways before the start of the War. It seems that at one stage these were considered for conversion into a landplane variant of the Short-Mayo composite system. When war was declared, work on the two new aircraft at Hamble was halted and they were mothballed. By the start of 1941, with the sea route across the Mediterranean blocked, an air route across the middle of Africa to transport vital personnel and parts to the British forces in Egypt was opened. The few British Airways Lockheed L-10 Electras and Lodestars along with RAF Bristol Bombay aircraft available to fly the route needed reinforcing and an aircraft in the class of the Ensign was desperately needed, although the limited power available from their Tiger engines would be a liability in the hot-and-high climate. So it was decided to start work again on the two Ensigns mothballed at Hamble and fit them with more powerful American Wright Cyclone R-1820-G102A engines giving 1,100 horsepower and driving American Hamilton constant-speed propellers. The choice of Wright Cyclones was probably prompted by them being used on the British Airways Electras and some of the Lodestars already flying the trans-Africa route. Only a couple of years earlier it would have been unthinkable to fit a British airliner with US engines, any such move would no doubt have produced a sneering editorial in The Aeroplane magazine from CG Grey, along with being denounced in the British newspapers owned by Lord Beaverbrook.⁸ How things had changed!

Hamble was an incredibly exposed site for aircraft production. Situated on the Solent estuary, it presented an easy target for both day and night bombing. The Supermarine factories at Woolston and Itchen, both further up the estuary, had been put out of action by bombing in 1940. But Hamble seemed to lead a charmed life, only one person was killed on the airfield (that was in February 1943 by a strafing attack) but numerous attempts to bomb the airfield all failed to hit anything. The first of the "new" Ensigns (G-AFZU Everest) with Cyclone engines took to the air in June 1941, followed by G-AFZV Enterprise in November of the same year. These aircraft were joined by G-ADSU Euterpe which was repaired at Hamble and upgraded with Cyclone engines. This new form of the Ensign was called the Mark 2. The remaining Ensigns were also updated to Mk 2 standard at the BOAC maintenance facility at RAF Bramcote near Nuneaton. In fact the first "Mk 2" to be ready was the original G-ADSR Ensign, which set off for Africa on the 23rd of October 1941. The rest of the fleet was slowly converted to be sent off to operate the trans-Africa air route. The last to go was G-ADSS Egeria, in February 1943.

The original G-ADSR Ensign after conversion to Mk II standard, with Wright Cyclone engines.

Everest and Enterprise were the only large, 4-engined airliners to be built in Britain from late 1939 through until 1942 (a trickle of production of Avro Yorks began in 1943). The upgrade of the fleet to Mark 2 standard gave slight increases to the maximum speed (up to 210 mph from 205 mph) and cruising speed (up to 180 mph from 170 mph), a significant increase in speed of climb (900 feet per minute from 600 fpm) and maximum ceiling (up to 24,000 feet from 18,000 feet, although being unpressurised the increase in ceiling was of little use when carrying passengers). The stripping out of many of the fittings and cabin walls associated with its luxurious airliner origins, down to a more utilitarian standard, enabled the disposable payload to be increased from 9,580 lbs to 12,000 lbs. The range of the Mk 2 was considerably greater than the Mk 1, enabled by the fitting of additional fuel tanks (see box article about the Ensign's range further down the page).

The first built-as new Mk 2 Ensign to attempt the trip to Africa almost did not make it; on the 20th November 1941 G-AFZU Everest ran into a Heinkel He 111 bomber over the Bay of Biscay. The defenceless Ensign was raked with gunfire, only escaping by going into a high-speed dive (so fast the cockpit glazing cracked under the air pressure). Levelling out just above the sea, Everest returned to the UK where she was repaired at Bramcote to later complete her flight to Africa.

Ensign G-AFZU Everest, first of the Mk 2s to be built as new. The Wright Cyclone was a single-row radial engine, unlike the AS Tiger which had two rows, you can see the cowling is shorter. This is the Ensign that was attacked by a He 111 bomber over the Bay of Biscay.

The other built-as-new Ensign Mk 2, G-AFZV Enterprise, developed problems in three of its four engines on its flight to Bathurst in Gambia on 1st February 1942. For the long trip, the aircraft had been fitted with additional oil tanks in the fuselage to top-up the engine oil during flight via a manually operated pump; with no gauge to give feedback, it seems the operation of the pump may have been a bit overzealous, leading to the engine problems. Enterprise had to put down on a beach in West Africa controlled by the Vichy French. The crew and passengers were rescued by a Sunderland flying boat but the Ensign was recovered by the French, repaired and put into service by them as F-BAHD and renamed Nouakchott (after the name of the town it was recovered to, now capital of Mauritania). Their use of the aircraft was only made possible by the discovery of a stash of spare parts left at Le Bourget airport from when the Ensign had been used on the London to Paris route in 1939. It was used in French West Africa for a while and was then flown to France in October 1942. The following month it was seized by the Germans when they occupied the Vichy territory. The Germans were only interested in its Wright Cyclone engines, which they needed as spares for a number of pre-war DC3 aircraft they still operated. It was stripped of its engines in June 1943 and scrapped in late 1943.⁹

G-AFZU Everest, pictured coming in to land at Almaza (Heliopolis) in Egypt in 1943.

Ensign G-ADSV Explorer at the British airfield at Takoradi (in modern Ghana, then called the Gold Coast). Notice that part of the side of the engine nacelles could be folded out to form small maintenance platforms. The lineup of Wellington bombers in the background are ready to be ferried across Africa. The fuel truck is especially stylish!

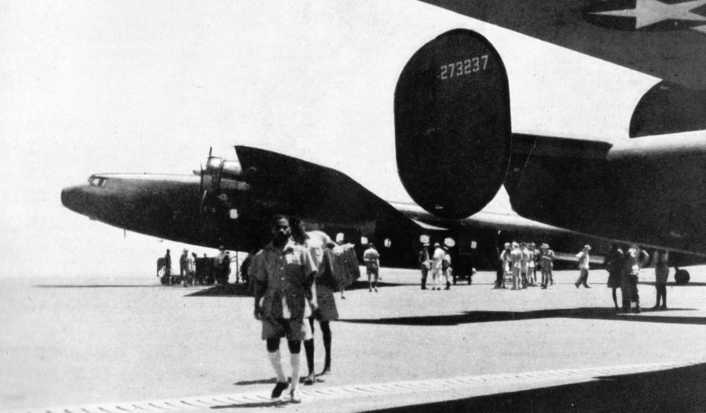

The British air route across Africa was later supplemented by one developed by the Americans to help supply the British in North Africa and also ferry equipment and personnel via India to support China. Here is an Ensign at the American airfield at Accra in Nigeria with an American B-24 Liberator in the foreground.

Ensign G-ADSV Explorer at the British airfield at Takoradi (in modern Ghana, then called the Gold Coast). Notice that part of the side of the engine nacelles could be folded out to form small maintenance platforms. The lineup of Wellington bombers in the background are ready to be ferried across Africa. The fuel truck is especially stylish!

The British air route across Africa was later supplemented by one developed by the Americans to help supply the British in North Africa and also ferry equipment and personnel via India to support China. Here is an Ensign at the American airfield at Accra in Nigeria with an American B-24 Liberator in the foreground.

In Africa, the Ensigns performed an important role. Many people must have blessed their existence, sparing them the long sea voyage around the Cape of Good Hope. The airfield at Asmara in Eritrea, captured from the Italians, was developed as the main engineering base for the Ensigns during this period of their use. After the Americans took on the majority of the airlift task across Africa, the Ensigns operated on the "spur" up from Asmara to Cairo. When the Mediterranian was opened to shipping again the Ensigns moved further east, providing an air link from Cairo through to the Persian Gulf and onwards, across India to Calcutta. Thus, at last, fulfilling the role they had been designed for. This settled down to a regular service, running three times every week. Around this time the fleet discarded their camouflage and reverted to their original silver finish. In the hot climates the Ensigns operated in, it was found that the cooling gills on the cowlings of the Cyclone engines were having to be left in the open position all the time. So to cut down on drag the gills were usually removed altogether. Because of the different handling qualities of the Ensigns, the BOAC crews favoured certain aircraft and those built up more flying hours than the less well-liked aircraft.

Ensign G-ADSV Explorer at Almaza (Heliopolis).The short engine cowlings show it has been upgraded to Mk 2 standard.

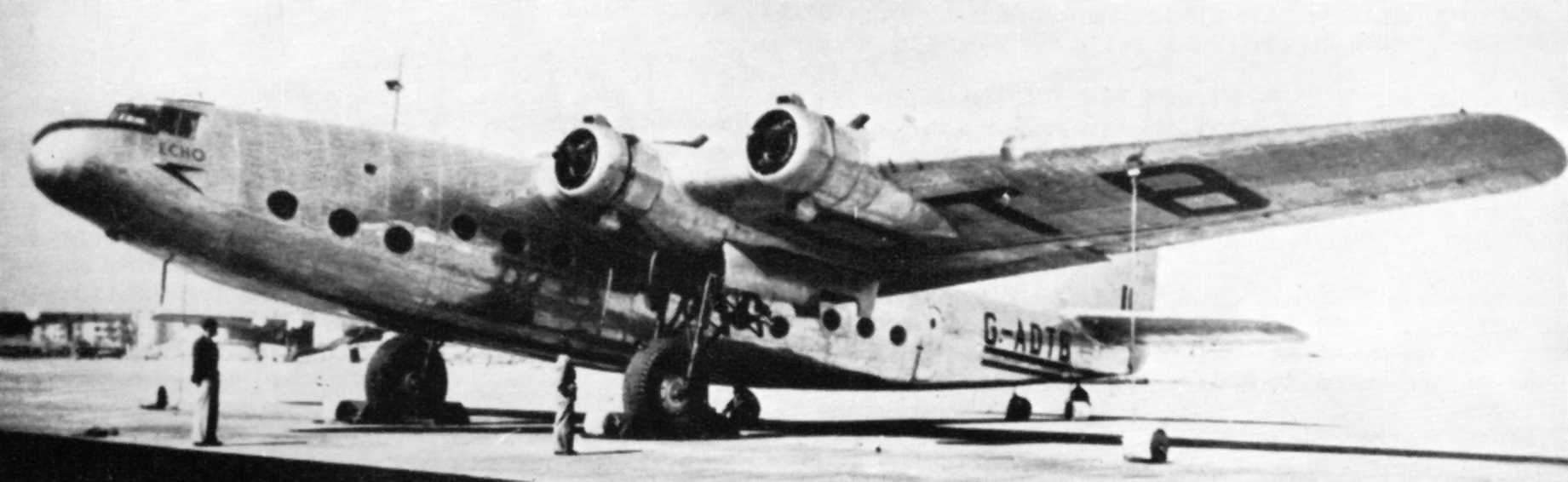

Ensign G-ADTB Echo, also at Almaza near Cairo in Egypt. Note that the rear fuselage is further off the ground than other Ensigns, due to it being fitted with a larger tailwheel from a Lancaster bomber. This was reported to result in an increase to the landing run.

Ensign G-ADTB Echo, also at Almaza near Cairo in Egypt. Note that the rear fuselage is further off the ground than other Ensigns, due to it being fitted with a larger tailwheel from a Lancaster bomber. This was reported to result in an increase to the landing run.

An inspection of the first Ensign (G-ADSR) at Cairo, at the end of 1944, revealed damage that was uneconomic to repair, so it was scrapped there early the following year. By mid-1945, parts for the version of Wright Cyclone engine used on the Ensigns (the R-1820-G-102A) were in short supply (due to the end of Lend-Lease) and deterioration of the fabric portions of the wings was starting to cause issues. So it was decided to retire the Ensigns from BOAC service. All the remaining aircraft were collected together at Almaza late in 1945 to be refurbished before being returned to the UK. Euterpe was broken up to provide spares for the surviving 7. The first Ensign to be sent back, G-ADSW Eddystone, had undercarriage failure and had to do a wheels-up landing at Castel Benito in Libya, on January 1st, 1946. Pits had to be dug to allow the undercarriage to be lowered. With its wheels locked down, it was flown back to Almaza for full repairs and then flown back to the UK in June 1946. Thus, although it was the first to set off back for England, it was the last to arrive. The Ensigns flew into the BOAC international reception airfield at Hurn, near Bournemouth, where they were stripped of equipment of use to BOAC. There was some interest expressed in continued use by start-up airlines. To this end, the Ministry of Supply paid for one of the Ensigns (G-ADSY Empyrean) to be stripped down to determine the costs involved in refurbishing the fleet. When the cost was relayed to potential purchasers they all deemed it to be uneconomic to buy them. So the Ensigns were flown the short distance to Hamble, their birthplace, to be disassembled. The major components were then taken by road to No 1 Metal and Produce Recovery Depot (1 MPRD) at Cowley near Oxford, where the metal parts were fed into the furnaces for recycling.

G-ADSW Eddystone being recovered at Castel Benito in Libya (now Tripoli International Airport). Notice the silver finish with BOAC "speedbird" logo and the crudely applied dark (black?) anti-icing paint on the leading edge of the fin.

Ensign G-ADTB Echo, pictured at Hurn airport in February 1946. Again, note the higher position of the rear fuselage due to the use of a larger tailwheel from a Lancaster bomber.

For all the adventures of the Ensign fleet, perhaps one thing should be remembered above all; not a single person died flying in an AW Ensign. Testament to the inherent safety of the design and the skill of the crews that flew them.

Ensign specifications:

Wingspan: 123 feet (37.5 metres)

Length: 114 feet (34.74 metres)

Max payload: Mk 1, 9,580 lb (4,345 kg) Mk 2, 12,000 lb (5,443 kg)

Max Speed: Mk 1, 205 mph (330 kph) Mk 2, 210 mph (338 kph)

Cruise Speed: Mk 1, 170 mph (275 kph) Mk 2, 180 mph (290 kph)

Service Ceiling: Mk 1, 18,000 feet (5,486 metres) Mk 2, 24,000 feet (7,315 metres)

Range: See box below.

Engines: Originally four AS Tiger IX giving 810 horsepower, later changed to AS Tiger IXC engines giving 805 horsepower.¹ When converted to Mk 2 standard fitted with Wright Cyclone R-1820-G102A engines giving 1,100 horsepower.

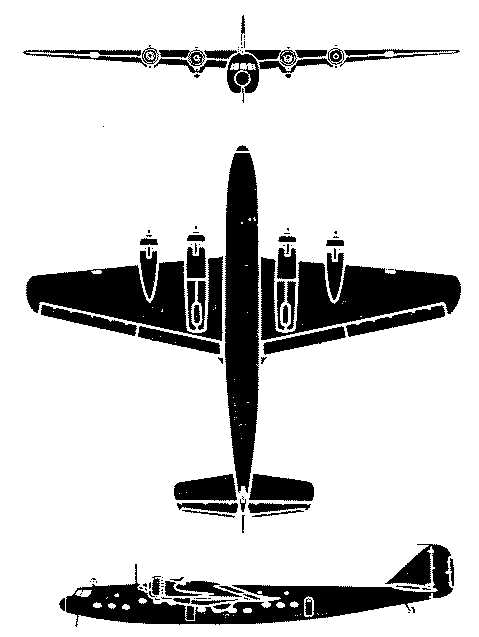

Ensign Mk 2, wartime recognition silhouette.

AW Ensign Range.

The range of the AW Ensign airliner is the subject of conflicting reports, with different figures being given in different articles and books. A letter by Peter W Moss in the 19th of April 1957 edition of Flight magazine, a follow on to his earlier article on the AW Ensign, goes a long way to clearing up the issue.

There were two sets of "range" recorded for the Ensign, one from the manufacturer was the maximum range in still-air with no reserve. However, both Imperial Airways and BOAC preferred to report the range of their aircraft with a 33.3 % reduction to give a leeway to account for headwinds.

The Mk 1 Ensigns were originally built with fuel tanks for 650 imperial gallons. This gave a range in still-air of 800 miles (1,287 km) although some sources say 860 miles (1,384 km). With an allowance of 33.3 %, this would give a modest range of just 534 miles (859 km) or 574 miles (924 km) with the latter figure, for regular airline service.

When upgraded to Mk 2 standard, Ensigns had fuel tanks for 1,064 imperial gallons. The extra tanks were in the area of what had been the "galley" cabin in the middle of the fuselage. This gave a still-air range of 1,143 miles (1,840 km), but with 33.3% reserves, this was reduced to just 857 miles (1,340 km).

Three Ensigns converted to Mk 2 standard, Egeria, Empyrean and Euterpe, had two additional fuel tanks, each of 354 imp gallons, in the wings (perhaps installed in the "crawl-space" in the wings). This increased the total fuel carried to 1,772 imp gallons. This gave a still-air range of 1,900 miles, (3,058 km) with a 33.3% reduction that resulted in a reported range of 1,425 miles (2,293 km) although some sources report 1,370 miles (2,205 km).

Individual Ensign Histories.

G-ADSR Ensign: Built to "Empire" (20-seat sleeper) configuration. First flight 24th January 1938. Converted to Mk 2 standard at Bramcote. First Ensign to fly out to for wartime service in the Middle East and Africa, departing the UK on the 23rd of October 1941 and arriving in Cairo on the 1st of November 1941. Damaged at Apapa in Nigeria on 4th September 1942 by mistaken retraction of undercarriage. It suffered a bird-strike on 22nd March 1944, The full extent of the damage suffered at Apapa was not revealed until an overhaul in September 1944. Scrapped at Cairo, 3rd January 1945. Recorded as having flown for 2,099 hours and covered 286,240 miles.

G-ADSS Egeria: Built to Empire configuration. Originally planned to be used by Indian Trans-Continental Airways as VT-AJE Ellora. First flight 26th May 1938. Had additional fuel tanks fitted in the wings when converted to Mk 2 standard at Bramcote. Sent to the Middle East in February 1943. Scrapped at Hamble, 13th April 1947. Recorded as having flown 2,686 hours and covered 382,707 miles.

G-ADST Elsinore: Built to Empire configuration. First flight 7th November 1938. Prepared for a one-way sabotage mission to Norway in April 1940 (called off). Converted to Mk 2 standard at Bramcote. Flew out to Middle East, departing UK on the 1st of June 1942. Slightly damaged in a taxying collision with a Lockheed Lodestar at Almaza (Cairo) in July 1942, but quickly repaired. Damaged on landing at Jiwani in May 1944 when one wheel would not extend, again quickly repared. Suffered a bird strike in October 1944, again quickly repaired. Departed Egypt for the UK on the 6th Feb 1946. Scrapped at Hamble, 28th March 1947. It is recorded that Elsinore had clocked up 3,495 flying hours and covered 492,770 miles.

G-ADSU Euterpe: Built to Empire configuration. Originally planned to be used by Indian Trans-Continental Airways as VT-AJF Everest. First flight 12th January 1938. Crashed at Bonniksen's airfield near Leamington Spa on 15th December 1939. Repaired and updated to MK 2 standard at Hamble, it flew again on 8th July 1942. Had additional fuel tanks fitted in the wings when converted to Mk II standard. Flew out to the Middle East in November 1942. Scrapped at Cairo, 21st April 1946. Recorded as having flown 406,061miles.

G-ADSV Explorer: Built to Empire configuration. First flight 24th November 1938. Slightly damaged by enemy bombing at Whitchurch on 24th November 1940. Converted to Mk 2 standard at Bramcote. Flew out to the Middle East, departing the UK on the 2nd of May 1942. Scrapped at Hamble, 23rd March 1947. Recorded as having clocked up 3,720 flying hours and flown 528,360 miles (the highest mileage of the Ensign fleet).

G-ADSW Eddystone: Built to European (40-seat) configuration. First flight 11th December 1938. Modified to Mk 2 standard at Bramcote. Flew out to the Middle east, deparing the UK on the 5th of March 1942. Wheels-up landing at Castel Benito in Libya on 1st January 1946. Patched up and flown back to Cairo for full repairs. Left Cairo for Hamble on 3rd June 1946. Scrapped at Hamble, 21st April 1947. Flew 3,595 hours and covered 502,047 miles.

G-ADSX Ettrick: Built to European configuration. First flight 27th February 1939. Destroyed at Le Bourget. 1st June 1940.

G-ADSY Empyrean: Built to European configuration. First flight 19th June 1939. Slightly damaged by enemy bombing at Whitchurch on 24th November 1940. Had additional fuel tanks fitted in the wings when converted to Mk 2 standard at Bramcote. Flew out to the Middle East in December 1942. Scrapped at Hamble, 26th March 1947. Flew 3,478 hours and covered 501,675 miles.

G-ADSZ Elysean: Built to European configuration. First flight 25th June 1939. Destroyed by strafing Bf109 fighters at Merville in France, 23rd May 1940.

G-ADTA Euryalus: Built to Empire configuration. First flight 19th August 1939. Originally planned to be used by Indian Trans-Continental Airways as VT-AJG Ernakulam and briefly painted with that serial before its first flight. On 23rd May 1940 damaged by enemy fire on flight back from Merville and crash-landed at Lympne aerodrome in Kent. Broken up and parts used to repair G-ADSU Euterpe at Hamble.

G-ADTB Echo: Built to Empire configuration. First flight 30th August 1939. On 23rd May 1940 rudder was slightly damaged by enemy fire on flight back from Merville. Slightly damaged by enemy bombing at Whitchurch on 24th November 1940. Upgraded to Mk 2 standard at Bramcote. It flew out to the Middle East in 1942 (possibly July). Known to have been fitted with the tailwheel from a Lancaster bomber some time in 1944. Scrapped at Hamble, 20th March 1947. Flew 3,534 hours, covered 507,083 miles.

G-ADTC Endymion: Built to Empire configuration. Originally planned to be used by Indian Trans-Continental Airways as VT-AJH Etah. First flight 5th October 1939. Destroyed by bombing at Whitchurch (Bristol) aerodrome on 24th November 1940.

G-AFZU Everest: Originally ordered by BOAC to be built in Empire configuration. Construction was delayed and completed to Mk 2 standard. First flight was on 20th June 1941. Attacked by Heinkel He111 over Bay of Biscay on 9th November 1941 and returned to UK. Repaired at Bramcote, it flew out to the Middle East in April 1942. Scrapped at Hamble, 16th April 1947. It flew 2,406 hours, distance covered not recorded.

G-AFZV Enterprise: Originally ordered by BOAC to be built in Empire configuration. Construction was delayed and completed to Mk 2 standard. First Flight on 28th October 1941. Wheels-up landing on a beach in French West Africa. Recovered by French and used as F-BAHD. Seized by Germans, stripped of engines and scrapped in late 1943.

What If?

Ensign painted as if it had seen more large-scale use in the European theatre

With hindsight, the British decision to stop all production of transport aircraft at the outbreak of war was undoubtedly the wrong choice. While aircraft of dubious value to the war effort like the Blackburn Botha and Handley Page Hereford were being produced the potential of transport types like the Ensign were ignored. Even if production at Hamble had only continued at the rate of one per month, the additional twenty to thirty aircraft produced until the Avro York entered limited production (in 1943) would have been a massive boost to Britain's air-lift capacity (remember that the old fixed-undercarriage Handley Page Harrow continued to be used as a transport aircraft until May 1945). The Ensign might have made a good paratroop-dropping aircraft, its nose-down flying attitude helping avoid entanglement on the tail (the Avro York proved to be ill-suited for dropping paratroops).

Notes

¹ Many descriptions of the Ensign list the Tiger IXC engine as having a rating of 850 horsepower. This seems to confuse the IXC with the Tiger VIII and X which were the versions of the engine used on the Whitley bomber, these had two-speed superchargers, giving more power at height than the IX and IXC versions used on the Ensign. The best sources I can find (contemporary engine worksheets) credit the Tiger IX with 810 hp when cruising and 880 hp for short periods for take off. The Tiger IXC engine had more power (935 hp) for short periods for take off but it seems to have been slightly less powerful (805 hp) when cruising. The authorative "British Aero-Engines and Their Aircraft" by Alec Lumsden (see sources below) confirms the cruising horsepower but gives different figures for the take-off power in its appendix. It also credits the IXC with being 32 lbs (14.5 kg) lighter than the IX.

² The location of the crash is variously given as "Bonnington" and "RAF Chipping Warden" in articles and internet pages. Some articles even claim that the aircraft crashed twice that month! Sustaining major damage at the two different airfields! The origin of the "Bonnington" crash site is easily explained. It was first mentioned in an article on the Ensign by Peter W Moss in Flight magazine in February 1957 (see sources below). He had simply misheard the name "Bonniksen's" as "Bonnington" (in the original article he did specify it was near Leamington). Some months later he wrote a postscript to his article for Flight magazine (published in its letters column in the 19th April 1957 edition) where he put the record straight that Euterpe had crashed at "Leamington airfield" also known as Bonniksen's airfield. This was a tiny privately-owned airfield to the south-east of Leamington Spa, sandwiched between a railway line and a road. Unfortunately, the "Bonnington" name was repeated in an article in Aeroplane Monthly in 1979 (see sources below). This prompted an exchange of correspondence in its letters column where two readers wrote in to confirm the crash site being Bonniksen's airfield. The first letter by Kenneth Aitken appears in the June 1979 edition, and the other by B. Bailey-Hickman appears in the August 1979 edition. The origin of the "RAF Chipping Warden" crash site mistake is harder to pin down. The first mention of "Chipping Warden" would seem to be in Oliver Tapper's book "Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft since 1913" and it's logical to assume Tapper was working from Armstrong Whitworth's files. No Ensign can have crashed there in December 1939, because the RAF airfield at Chipping Warden did not open until July 1941, some 19 months later. We know that there was at least a four-month gap between the crash at Bonniksen's Airfield and the return of the aircraft to Hamble. It would have been difficult to accommodate the huge Ensign at such a tiny airfield, and it is logical to assume it was moved by road to another location before being taken to Hamble in the spring. The team sent to recover the aircraft in the spring may have assumed the aircraft had crashed at the airfield it had been stored at. The site of the RAF airfield at Chipping Warden is only 16 miles from Bonniksen's Airfield, albeit it would mean negotiating the airframe through some very twisty country roads on the way (remember this was pre-motorway). However, as this airfield did not open until July 1941, it can be ruled out. There is another possibility; close to Bonniksen's airfield (only half a mile away) runs the "Fosse Way", the old straight Roman road that runs from Lincoln to Exeter. The logical way to get the aircraft back to Hamble would be along this straight road as far as possible (it does not go through any major towns) and after turning off this route the aircraft would pass the RAF airfield at Chipping Norton (now returned to agricultural use and owned by Jeremy Clarkson). This would seem a much more appropriate place to store the aircraft until Hamble was ready to repair it. However, again we have an issue of timing since Chipping Norton did not officially open until June 1940, although the land must have been owned by the Government well before then and building work on the site was probably well underway in late 1939. One can envisage a train of events whereby the Ensign was recorded as delivered to Hamble after "recovery from Chipping Norton", then later, someone who knew the Ensign crashed further north in the Midlands comes along and thinks "that can't be right" and assumes that the crash site must have been the similar sounding Chipping Warden, altering the records to suit.

³ The story of the development of the aircraft-mounted mine-sweeping ring is told in "Rings and Things" an article by Norman Parker in Twentyfirst Profile magazine, volume 1, number 9.

⁴ A letter by R.C. Hockey, in the "Skywriters" letter column of Aeroplane Monthly magazine's August 1979 edition, reveals the plan to use an Ensign on the sabotage mission to Norway. It says the Ensign was on the runway, ready to take off, when the mission was cancelled. I presume that the letter's author is Ronald Clifford Hockey DSO, DFC, who flew many flights to land or parachute resistance fighters into occupied Europe. The letter identifies the other pilot on board the mission as Flt Lt Henry Bernard Collins. John Collins, the son of Flt Lt Collins, remembers his father returning home, armed with two pistols, from the planned "one-way" mission to Norway.

⁵ A short account of the events at Merville aerodrome that day can be found in the article "An Airline at War" by Herman De Wulf in "Air Enthusiast Quarterly" magazine, issue 13 August-November 1980. A squadron of Defiant turret fighters (264 Sqdn) had been detailed as escorts for the mission to Merville but were cancelled (see the book "Defiant Mk I Combat Log" by Hugh Harkins, Centurion publishing). From a description of events in the HMSO book "Merchant Airmen" (see sources below) it seems that the airliners were escorted by Hurricane fighters (probably No 253 Squadron based at Kenley) who clashed with the German Bf109 fighters for some 20 minutes, allowing the airliners time to unload. Only when the RAF fighters had to depart because of lack of fuel, did the Germans strafe the airfield. "The Battle of France -Then and Now" (see sources) lists one Hurricane of 253 Squadron lost and another crash-landed back in the UK and two Bf109s of 2/JG27 shot down and another crash-landed as a possible result of the clash near Merville. According to the account in "Merchant Airman", the Captain (John M.H. Hoare) and First Officer of G-ADSZ Elysian, which had been destroyed, got aboard one of the other aircraft but that aircraft was shot down and Captain Hoare was killed (he is buried at Arques in France). The account says it was a de Havilland DH86 that was shot down, but I can find no record of a DH86 being lost that day, it was most likely he was aboard the Belgian S73 (OO-AGS) that is known to have been shot down near Arques.

⁶ The story is written up in a report by Flt Lt Collins straight after the event (see sources below). The same incident is also detailed in Air Marshall Sir Victor Goddard's memoir "Skies to Dunkirk" (again, see sources listed below), who was one of the officers flown back on the Ensign. They differ on a couple of points, but Goddard's account was written years after the event, and Collins' report seems the most reliable. Goddard says he was given a personal briefing by General Lord Gort, commander of British forces in Northern France, to give to the Chiefs of Staff, stressing the seriousness of the situation and asking that every possible ship should be sent to help in the evacuation. Which would mean this Ensign played a crucial role in the story of Dunkirk.It is a pity that neither account records the actual identity of the Ensign concerned.

⁷ Extract from "The Diary of a Staff Officer - Air Intelligence Liason Officer - at Advanced Headquarters North B.A.F.F. 1940" - Written anonymously and published by Methuen & Co, London in February 1941. This entry is dated for 10.15 am on June 17th 1940. The follow-on entry for that night reports the anonymous officer being evacuated from Nantes airfield by a Blenheim bomber.

⁸ Notable for his fascist sympathies and xenophobic views, CG Grey editor of The Aeroplane, trotted out tedious anecdotes about the perceived unreliability of US-produced aero-engines. He was dismissed as editor of The Aeroplane when war was declared. However, his prejudices had taken root and were reinforced by calls in the newspapers owned by Lord Beaverbrook to reject the purchasing of American aircraft and engines. Intelligence reports from the U.S. embassy in London noted that the aversion to using US engines had only stopped after the delivery of Lockheed Hudsons and it was found that their Wright Cyclone engines (the same type as later used on the Ensign) were as reliable, if not more so, than British aircraft engines (see declassified US file G-2/813-314, Air Bulletin No 11, "Air Operations in European War", May 8th 1940).

⁹ The full story of the Ensign in French service is told in Philippe Ricco's article "Flag of Convenience" (see sources list below). The article refutes the rumour that one or two of the Ensigns were operated by the Luftwaffe.

Links

Newsreel video of AW Ensign on Youtube.

Newsreel video of the AW Ensign under construction on the Pathe website.

Newsreel video of AW Ensign on Youtube.

Newsreel video of the AW Ensign under construction on the Pathe website.

Sources

"Merchant Airmen - The Air Ministry Account of British Civil Aviation: 1939-1944" - HM Stationary Office (SO Code 70-481) 1946. Its third chapter has accounts of the events at Merville on the 23rd May 1940 and other Ensign missions in France. Chapter 9 mentions the Ensign's use on the trans-Africa air route. It was reprinted in 2018 by Air World Books under the title "Airliners At War - British Civil Aviation, 1939-1944, an Official History" (ISBN 978-1-47389-409-9) with some slight alterations in the text. Some of the photos are different, with those in the reprint often being reproduced in poorer quality than the original.

"Ensign Class - The History of a Fleet of Airliners that went to War." - Articles by Peter W Moss in the 15 Feb and 22nd Feb 1957 Editions of Flight Magazine. This was followed up by a postscript by Peter W Moss in the letters column of the magazine's 19th April 1957 edition. This is the most authoritative overview of Ensign operations, albeit the one that started the erronious "Bonnington" crash site story in the original article (corrected in the postscript).

"Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft since 1913" by Oliver Tapper , first published by Putnams in 1973. A great description of the development of the Ensign, drawn from manufacturer's records. It does include the erronious claim that Euterpe crashed at Chipping Warden.

"Ensigns for the Empire" - a two-part article by Ray Williams in the March and April 1979 Edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine. It erroniously quotes "Bonnington" as the crash site for Euterpe. This was corrected by reader's letters in the June and August editions of the magazine.

"Cuckoo in the Nest - Assembling AW Ensigns at Hamble." - an article by Roy Bonser and Ken Ellis in Air Enthusiast Quarterly magazine issue 69, May/June 1997.

"AW Ensign Database" - An 18 page in-depth article in Aeroplane Magazine of March 2015. By far the biggest set of data on the Ensign out there. However, it does manage to erroniously claim that Euterpe crashed twice in December 1939. The figures for the power of the various engines are also incorrect, as is the reported use an Ensign by the Luftwaffe.

"Flag of Convenience" - An Article by Philippe Ricco in Issue 21 of "The Aviation Historian" magazine (October 2017). It tells of the recovery and use of "Enterprise" by the French and also features photos of the burnt-out wrecks of both Elysian and Ettrick, proving that no Ensign could have been captured and operated by the Luftwaffe. It also clears up contradicting reports about what serial number the French applied to "Enterprise".

An article in the "Probe Probare" series by Alec Lumsden and Terry Heffernan in the May 1985 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine covers the testing of the Ensign by A&AEE at Martlesham Heath.

"Elsinore Shows her Colours" - A short article by Philip Jarrett in the December 1990 edition of Aeroplane monthly. It features a striking colour photo of G-ADST Elsinore in the Middle East by Maynard Owen Williams for the US National Geographic Society.

"Report on Flight, Hendon-Croydon-Seclin-Hendon" by Flt Lt H.B. Collins, a report to officer commanding No 24 Squadron. The report was relayed to me by John Collins, the son of H.G. Collins.

"So Few - The Immortal Record of the Royal Air Force" - By David Masters, published by Eyre & Spottiswoode. This book was revised and reprinted many times from 1941 until 1946. The 1946 version has the story of the Ensign flight by Flt Lt H.B. Collins on pages 188-189.

"Skies to Dunkirk - A Personal Memoir" - by Air Marshal Sir Victor Goddard. Published in 1982 by William Kimber. ISBN: 0-7183-0498-5.

"What became of Louis Strange?" - An article by Peter Hearn in "Air Enthusiast Quarterly" magazine, number 43.

"Flying Rebel - The Story of Louis Strange" - By Peter Hearn, published in 1994 by HMSO for the RAF Museum, ISBN 0 11 290500 5. The recollections of Lous Strange reproduced in this book implies that Ensign G-ADSZ Elysian was destroyed at Merville on the 21st May, the same day that Louis Strange arrived to supervise the recovery of the abandoned Hurricanes. All other sources indicate that the Ensign was destroyed on the 23rd May.

"British Piston Aero-engines and their Aircraft" - By Alec Lumsden, published by Airlife in 1994, ISBN - 1 -85310 - 294 -6.

"British Civil Aircraft 1919-1959" - A.J Jackson, Putnam, 1959.

"The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Propeller Airliners" - Editor Bill Gunston. Published by Windward. ISBN 07112 0062 9.

"The Battle of France - Then and Now" - By Peter D. Cornwall (After the Battle Publication, ISBN: 9-781870-067652) has a photo of the wrecked tail of G-ADSZ "Elysian" at Merville airfield along with records of the losses of the British 253 Squadron flying Hurricanes and the German 2/JG27 flying Bf109 fighters for the 23rd of 1940 that were associated with the action at Merville that day.

"Merchant Airmen - The Air Ministry Account of British Civil Aviation: 1939-1944" - HM Stationary Office (SO Code 70-481) 1946. Its third chapter has accounts of the events at Merville on the 23rd May 1940 and other Ensign missions in France. Chapter 9 mentions the Ensign's use on the trans-Africa air route. It was reprinted in 2018 by Air World Books under the title "Airliners At War - British Civil Aviation, 1939-1944, an Official History" (ISBN 978-1-47389-409-9) with some slight alterations in the text. Some of the photos are different, with those in the reprint often being reproduced in poorer quality than the original.

"Ensign Class - The History of a Fleet of Airliners that went to War." - Articles by Peter W Moss in the 15 Feb and 22nd Feb 1957 Editions of Flight Magazine. This was followed up by a postscript by Peter W Moss in the letters column of the magazine's 19th April 1957 edition. This is the most authoritative overview of Ensign operations, albeit the one that started the erronious "Bonnington" crash site story in the original article (corrected in the postscript).

"Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft since 1913" by Oliver Tapper , first published by Putnams in 1973. A great description of the development of the Ensign, drawn from manufacturer's records. It does include the erronious claim that Euterpe crashed at Chipping Warden.

"Ensigns for the Empire" - a two-part article by Ray Williams in the March and April 1979 Edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine. It erroniously quotes "Bonnington" as the crash site for Euterpe. This was corrected by reader's letters in the June and August editions of the magazine.

"Cuckoo in the Nest - Assembling AW Ensigns at Hamble." - an article by Roy Bonser and Ken Ellis in Air Enthusiast Quarterly magazine issue 69, May/June 1997.

"AW Ensign Database" - An 18 page in-depth article in Aeroplane Magazine of March 2015. By far the biggest set of data on the Ensign out there. However, it does manage to erroniously claim that Euterpe crashed twice in December 1939. The figures for the power of the various engines are also incorrect, as is the reported use an Ensign by the Luftwaffe.

"Flag of Convenience" - An Article by Philippe Ricco in Issue 21 of "The Aviation Historian" magazine (October 2017). It tells of the recovery and use of "Enterprise" by the French and also features photos of the burnt-out wrecks of both Elysian and Ettrick, proving that no Ensign could have been captured and operated by the Luftwaffe. It also clears up contradicting reports about what serial number the French applied to "Enterprise".

An article in the "Probe Probare" series by Alec Lumsden and Terry Heffernan in the May 1985 edition of Aeroplane Monthly magazine covers the testing of the Ensign by A&AEE at Martlesham Heath.

"Elsinore Shows her Colours" - A short article by Philip Jarrett in the December 1990 edition of Aeroplane monthly. It features a striking colour photo of G-ADST Elsinore in the Middle East by Maynard Owen Williams for the US National Geographic Society.

"Report on Flight, Hendon-Croydon-Seclin-Hendon" by Flt Lt H.B. Collins, a report to officer commanding No 24 Squadron. The report was relayed to me by John Collins, the son of H.G. Collins.

"So Few - The Immortal Record of the Royal Air Force" - By David Masters, published by Eyre & Spottiswoode. This book was revised and reprinted many times from 1941 until 1946. The 1946 version has the story of the Ensign flight by Flt Lt H.B. Collins on pages 188-189.

"Skies to Dunkirk - A Personal Memoir" - by Air Marshal Sir Victor Goddard. Published in 1982 by William Kimber. ISBN: 0-7183-0498-5.

"What became of Louis Strange?" - An article by Peter Hearn in "Air Enthusiast Quarterly" magazine, number 43.

"Flying Rebel - The Story of Louis Strange" - By Peter Hearn, published in 1994 by HMSO for the RAF Museum, ISBN 0 11 290500 5. The recollections of Lous Strange reproduced in this book implies that Ensign G-ADSZ Elysian was destroyed at Merville on the 21st May, the same day that Louis Strange arrived to supervise the recovery of the abandoned Hurricanes. All other sources indicate that the Ensign was destroyed on the 23rd May.

"British Piston Aero-engines and their Aircraft" - By Alec Lumsden, published by Airlife in 1994, ISBN - 1 -85310 - 294 -6.

"British Civil Aircraft 1919-1959" - A.J Jackson, Putnam, 1959.

"The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Propeller Airliners" - Editor Bill Gunston. Published by Windward. ISBN 07112 0062 9.

"The Battle of France - Then and Now" - By Peter D. Cornwall (After the Battle Publication, ISBN: 9-781870-067652) has a photo of the wrecked tail of G-ADSZ "Elysian" at Merville airfield along with records of the losses of the British 253 Squadron flying Hurricanes and the German 2/JG27 flying Bf109 fighters for the 23rd of 1940 that were associated with the action at Merville that day.