Dinger's Aviation Pages

The Hawker Henley

The story of Britain's forgotten dive bomber, relegated to target-towing.

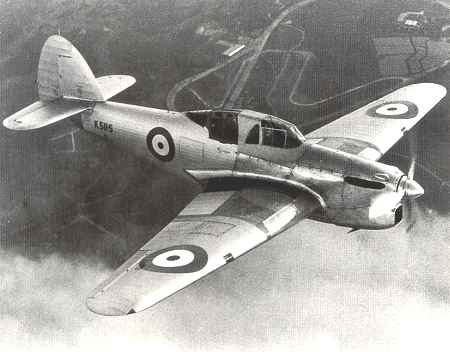

A Hawker Henley in flight. One contemporary publication described the Henley as: "Streamlined, bullet-nosed, with wings rather like the fins of a gigantic fish." .

Origins.

Origins.

The Hawker Henley is one of the most intriguing "what-ifs" in the history of aviation, yet this is not an aircraft that existed as only a paper exercise, or a partly built prototype, or even a flying prototype that was cancelled. No, this was an aircraft that actually went into production with 200 examples built. This was an aircraft that pilots loved to fly, had an outstanding performance and was both rugged and reliable. So what went wrong? Why is this aircraft regarded as one of the great "what-ifs"?

To try to answer this question you need first to understand the fundamental difference between British air strategy at the start of the Second World War and that of the German Luftwaffe. The RAF was established from the merger of the Army's Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Navy's Royal Naval Air Service as an independent strategic air service. The important word here is strategic. The RAF's principal aim was the destruction of the enemy's means of war production. All other uses of airpower for tactical purposes were secondary. As far as support for the British Army was concerned it was only felt necessary to provide artillery observation aircraft (the Westland Lysander) and the bare minimum of fighters (a few squadrons of Hawker Hurricanes) to try to shoot down the opposing artillery observation aircraft. Why bomb individual targets on the front line when you could destroy the factories that made the tanks, guns and ammunition? The Germans had the opposite view, the front line at the point of attack (the Germans have a word for it, the "schwerpunkt") was the central focus for airpower, with Ju87 Stukas and medium bombers hammered the railways and roads behind the lines to prevent the enemy from concentrating to resist the advance¹.

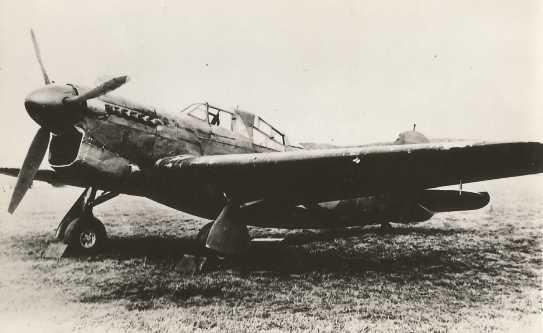

The prototype Hawker Henley K5115 in side-view. Notice that unlike the Hurricane the Henley had a retracting tail-wheel. The observer /gunner had pull-down side windows; a report in the March 1, 1939, edition of The Aeroplane magazine noted that these could be opened "without getting any draught at all". The semi-conical fenestration at the rear of the gunner's position could be rotated down into the fuselage to use a rear-mounted gun

So the very existence of Air Ministry Specification P4/34 calling for a two-seat, single-engined light bomber capable of dive bombing, issued in November 1934, is, at first sight, surprising and seems to suggest that the there was some move within the Air Ministry to provide a bomber capable of operating at the tactical level. It was this specification that gave rise to the Hawker Henley. Was there really such a fundamental change of policy? The RAF had always had two-seat, single-engined light bombers in its armoury, the DH4 and DH 9a in WWI and then a whole host of types in the 1920s leading to the outstandingly fast Fairy Fox and then the Hawker Hart and Hind. It should be stressed that these bombers were never expected to operate in direct support of the army in a European war, if they lacked the range to reach the enemy's centres of production they were expected to hit the railway networks bringing supplies to the front line, preferably hitting nodal points, marshalling yards and stations as far back from the front line as possible (these were the favoured targets for RAF two-seat bombers in the last year of WWI). Specification P4/34 was a natural next step; an aircraft to replace the Hawker Hinds in Bomber Command's fast day-bomber squadrons. The fact that it included a requirement to dive bomb is the misleading bit, the RAF seems to have never been seriously interested in true dive bombing at high angles, it never invested money in research and never developed true dive bombing sights (unlike the Germans who had fully automatic bomb sights that would even pull the aircraft out of its dive). The lack of dive brakes in the design show that true dive bombing was never a serious consideration. However, it could carry bombs under the wings to fall clear of the propeller and it was stressed for pullouts from dive bombing at fairly high angles (up to 70 degrees) and with proper training, this could have greatly improved the accuracy of bombing, maybe even doubling or trebling the number of direct hits on target. It is this aspect of dive bombing, as a "force multiplier" that is often overlooked.

Another view of the prototype K5115.

Another overlooked fact about the process of specifying this new "Hart replacement" was that Edgar Ludlow-Hewitt, then Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, put up a strong case for the new design to have two engines.³

The prototype flying over the famous Brooklands racing circuit, the centre of which housed the airfield from which it first flew. Note the panel in the starboard wing to allow access to the machine gun. The first prototype had fabric-covered outer wings when it first flew. The production Henley's wings were skinned in metal.

The Henley was partly rejected because of the existence of the Fairey Battle. The Battle was built to an earlier specification (P27/32) based on that of the Wellington twin-engined bomber! In the early 1930s, there was a real chance that the international disarmament conference would put a limit on the weight and size of bombers. The Battle was designed to meet the likely limits of such a treaty so that the RAF would still have a bomber force if the new Wellington, Whitley and Hampden designs were outlawed. The Battle, with its 3 crewmen, was a big aircraft. Go and stand next to the one at the RAF museum in Hendon and you will be amazed just how large it is. I remember as a lad building an Airfix kit of the Battle, putting it down next to my models of Spitfires and Hurricanes and wondering if Airfix had got the scale wrong! It is a testament to the streamlined form of the Battle that a lot of armchair-bound aviation pundits seem to think it was little more than a "stretched" fighter². It certainly was not. In fact, it was the Hawker Henley that could more properly be said to be an enlarged fighter; being based on the Hawker Hurricane, sharing the same outer wing design and undercarriage.

The prototype Henley and Hurricane flying together.

The other contender for the P4/34 specification was built by Fairey and only ever named after the specification number. It ended up being developed into the two-seat Fulmar fighter for the Royal Navy.

The other contender for the P4/34 specification was built by Fairey and only ever named after the specification number. It ended up being developed into the two-seat Fulmar fighter for the Royal Navy.

In construction, the Battle, although designed a couple of years before the Henley was much more advanced, being a full metal, stressed skin design with a monocoque fuselage (Fairey had benefited from close contacts with US aircraft manufacturers who had perfected stressed skin construction), while the Henley, like the Hurricane, still used a metal latticework covered with wooden frames and fabric to provide a streamlined fuselage. When Fairey Battles were first delivered, their performance greatly exceeded what had been expected. The original specification had called for a top speed of only 200 mph (322 kph), yet the Battle proved able to do over 250 mph (402 kph). You can imagine the Air Ministry big-wigs, having just signed up for massive orders of Fairey Battles looking at the Hawker Henley and wondering "Do we really need that as well?". The Henley did promise to be faster than the Battle, but its internal bombload was half that of the Battle and its range was slightly shorter. The Battle would be some 70 mph (112 kph) faster than the Hawker Hinds that then formed the RAF's fast day-bomber force and the extra 30 mph (48 kph) promised by the Henley might have seemed of little consequence. The Battle had the added advantage that its three-man crew enabled missions to be flown at night, with the observer/bomb aimer handling maps and acting as navigator while the rear gunner still kept a look out for night fighters. Air Ministry documents also show that there was growing concern about the Henley being undefended when the rear gunner used the bomb sight.

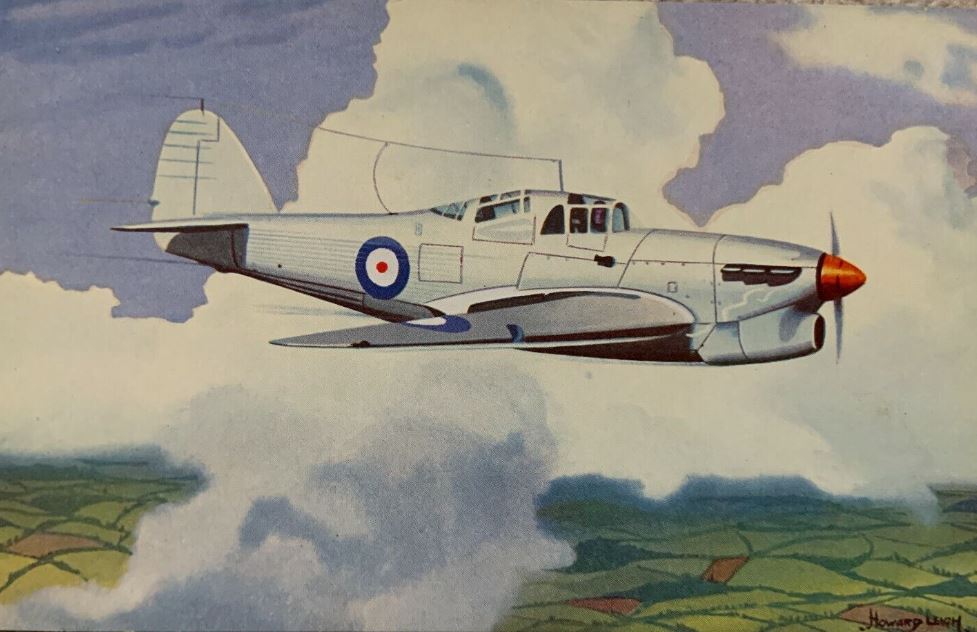

Pre-war postcard image of a Henley painted by Howard Leigh.

While this had been going on the RAF had also ordered the Bristol Blenheim twin-engined bomber, an aircraft that evolved from the civil "Britain First" small airliner. The Blenheim's development had not been prompted by any Air Ministry specification, but rather by pressure from the newspapers owned by Lord Rothermere who had ordered the "Britain First" as a means for his reporters to quickly fly around Europe but had then donated it to the Air Ministry. Developed into the Blenheim, it had a three-man crew (like the Fairey Battle), able to both man a defensive gun and aim the bombs at the same time. The Blenheim would have neatly fitted the bill for a twin-engined P4/34, as advocated by Ludlow-Hewitt. It was the adoption of the Blenheim alongside the unexpectedly high speed of the Fairey Battle that made the Air Ministry conclude that the Henley was no longer required.

This photo shows that the Henley prototype was tested with underwing bombs, a fact that is missing from all published descriptions of the aircraft. Carrying bombs under the wings would have done away with the need for a crutch to throw them clear of the propeller when dive bombing.

Another view of the Henley prototype K5115 with bombs under its wings.

Another view of the Henley prototype K5115 with bombs under its wings.

When the British sent forces to France in the autumn of 1939 they took large numbers of Fairey Battle bombers with them. It is important to stress again that the Battle squadrons were never meant to operate in support of the Army. They were there as the "Advanced Air Striking Force", an off-shoot of Bomber Command. Their task was to bomb factories, oil storage and strategic communication hubs in the Ruhr region of Germany. The Battles were never used in the strategic role planned for them. This was because the French, fearful of German reprisals, forbade their use against German targets. When the German Blitzkrieg began the Battle crews found themselves flung against German armoured columns and river crossings, targets they had never trained for. The Battles suffered heavy casualties.

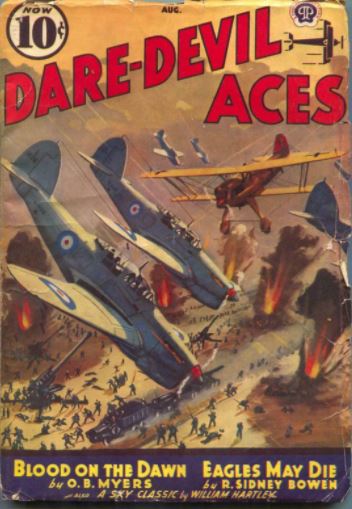

Frederick Blakeslee painted this cover for the American "Dare-Devil Aces" magazine for August 1939.It imagines Hawker Henleys attacking German troops and being attacked themselves by a Heinkel 51 biplane fighter.

Would the squadrons have fared better if they had used Hawker Henleys rather than Fairey Battles? If you are just talking about a straightforward swop of aircraft without any change in training and tactics then the answer is probably not. As a smaller, faster, more manoeuvrable machine it would have presented a harder target for German flak and fighters so that probably more crews would have survived to complete more sorties - but the end results would have been much the same. Only as part of a complete restructuring of the Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) and British Expeditionary Force Air Component (BEFAC) into a proper tactical air force with a doctrine for co-operation with the Army, training for identifying and attacking tactical targets, including dive bombing, could the Henley have stood a chance of success.

The underside of the Hawker Henley, showing the bomb bay which could accommodate two 250 Ib (113 kg) bombs. The two "bobbins" on either side of the fuselage are weights fitted when the aircraft was flying without a second crew member or with the Radio W/T equipment removed to keep the aircraft's centre of gravity correct, a feature common with earlier Hawker aircraft (you can see them still used on the Shuttleworth Collection's Hawker Hind and Demon). L3261 was an early casualty, crashing on landing at Catfoss airfield in July 1939.

Target Tug.

Target Tug.

Having rejected the Henley as a bomber the surprising thing is that it was still ordered into production but as a target tug. The production Henley was called the Mark III, presumably to distinguish it from the two prototypes (Mk I and II). Now the RAF did have an urgent need for a fast target-tug; the old biplanes they were using in the role simply did not give a realistic speed for practice by the new Spitfire and Hurricane fighters. But it still seems a strange use for an aircraft type that was probably the fastest twin-seat bomber design then flying. A production line was established at Hucclecote near Gloucester run by the Gloster aircraft company, then already part of the larger Hawker Siddeley group, and 200 Henleys were produced. The drogue for towing was wound back by a windmill arrangement that protruded from the side of the fuselage. As a target tug, the Henley had shortcomings, it was a bit like using a sports car to tow a trailer, the Merlin engine had to be run at high speed for long periods and so they wore out much more quickly than in normal use. The Henley's neatly faired coolant radiator was exactly the right size and efficiency for normal flying, but when towing a target at high engine speed but lower airspeed the lower flow of air through the radiator was insufficient to keep the engine cool and so overheating would occur. First used to tow small drogues for air-to-air target practice, the high wear on the engines meant that towing speeds had to be reduced and eventually the Henleys were switched to towing larger drogues for surface-to-air AA practice. In 1942 The Henley started to be augmented in the target towing role by Boulton-Paul Defiants and Miles Martinets. You would have expected the Defiant to suffer from the same engine problems as the Henley, having the same Merlin engine, but the Defiant's big belly bathtub radiator was better able to keep the engine cool. The Henley was not completely replaced until 1945 (the web link of Henley crashes at the bottom of the page shows continued activity through 1943-44-45 which contradicts the oft-repeated line that the Henley was retired in 1942). The last Unit to operate Henleys was Number 631 Squadron based at Towyn in North Wale.

Henley L3243, the first production Henley. Note the all-in-one, curved front windscreen. Although streamlined, it was criticised for being easily obscured by rain or oil. so they were modified to have a three-piece windscreen with an optically flat centre section, similar to the Hurricane.

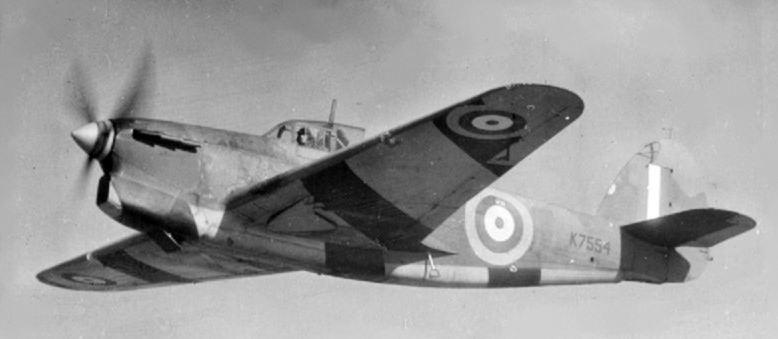

Henley K7554, the second prototype, in a factory-fresh silver finish, showing the windmill arrangement projecting from the port side of the aircraft. This was used to wind back target drogues.

The second prototype Henley K7554 pictured later in "tiger stripes" target tug colours. Note the pull-down step to aid getting onto the wing.

The Windmill arrangement on a Henley. It could be rotated into the upright position in order to wind back the target drogues.

Hawker Henley L3363 towing a drogue. This aircraft's engine failed leading to a belly-landing at Blackney Marshes on the Norfolk coast in December of 1941.

Henley L3288. It is likely that the use of orthochrome film makes the yellow underside of the aircraft look dark gray. This aircraft served with No1 AACU (anti-aircraft cooperation unit), 1605 flight and then 631 Squadron. Notice the "ribbed" appearance of the rear fuselage, formed of fabric stretched over a wooden framework that surrounded the main metal structure. This type of construction was already beginning to look old-fashioned when the Henley first flew. However, the same structure used on Hawker Hurricanes proved surprisingly strong and stood up to hits from German 20mm cannon shells better than the monocoque fuselage of the Spitfire, and was much easier to repair. The American Vought SB2U -3 Vindicator monoplane dive-bomber also had a fabric-covered rear fuselage..

Photo Reconnaissance Henley

A note in government files (Avia 46/119), uncovered by aviation historian Matthew Willis, indicates that the Henley was briefly considered for photographic reconnaissance duties. In a memo dated 4th October 1939, the Henley is listed amongst other aircraft considered for this purpose. It was noted that if Spitfires proved to be a failure in the role, then the Henley would be the next aircraft to be tried, although it would need the new Rolls-Royce two-speed supercharged engine (the Merlin XX). The various Spitfire reconnaissance variants proved to be an outstanding success, so there was no need for the Henley to be used.

Wasted Opportunity?

The real surprise in the Henley story is why it was not pressed into service during the emergency period of 1940-41. After the Battle squadrons had been torn to shreds over France and the evacuation from Dunkirk it seems incredible that the Henley was not seen as a stop-gap. In this period new squadrons were still being formed on Fairey Battles, the Fleet Air Arm flew dangerous missions to Norway from the Orkney Islands in Skua dive-bombers whose maximum speed was much slower than the cruising speed of the Henley! In East Africa, slow Vickers Wellesleys and biplane Fairey Gordons were being used against the Italians. In Malaya and Singapore, even at the end of 1941, the Vickers Vildebeest biplane was being used in a bomber role. All this while some 200 Hawker Henleys were being used as target tugs or stored in maintenance units. In this period the British Air Ministry ordered huge numbers of Brewster Bermuda and Vultee Vengeance dive bombers from the U.S.A. The Bermuda was an unmitigated failure that cost the UK taxpayers millions of pounds (the contracts were signed before lease-lend came into force and the U.S.A. insisted on payment and delivery of the aircraft which just cluttered up maintenance units). The Vengeance did prove itself a good dive bomber but only after considerable development problems were overcome. It seems incredible that the Henley was not utilised during this period. It would have needed armour protection for the crew added and self-sealing linings fitted to the fuel tanks to make it fit for combat, and these additions would have taken away something from the performance. But even with 10-15 mph lopped off the top speed it would still have out-performed the Vengeance in all but bomb load, and even that might have been equalled with the more powerful Merlins available later in the war.

Henley L3276 was tested at Boscombe Down with various combinations of underwing bombs. It went back to target-towing duties afterwards, serving with 631 Squadron at Towyn in North Wales. It force-landed in the river Dysynniin in Merionthshire on the 28th of February 1945.

Another view of Henley L3243. The first production Henley, it went on to serve with 1AACU, 1605 Flight and 631 Squadron. It was "struck off charge" in August 1944.

Another view of Henley L3243. The first production Henley, it went on to serve with 1AACU, 1605 Flight and 631 Squadron. It was "struck off charge" in August 1944.

Engine test-bed.

The Henley performed valuable service as an engine test-bed, The prototype K5115 was fitted with a Rolls-Royce Vulture engine, as was L3302. Henley L3414 served as a test-bed for the Rolls-Royce Griffon.

Above and below: Henley L3414 was used for testing of the powerful Rolls-Royce Griffon engine, used on late marks of the Spitfire, the Fairey Firefly and Shackleton maritime patrol aircraft. Despite the big chin radiator, it still looks an elegant aeroplane. One can only guess at the performance of a production version of the Henley fitted with a Griffon or late-model Merlin engine. One would expect it to be well above 300 mph.

The first Henley prototype, K5115 (see above), was used to test the Rolls-Royce Vulture engine, as used on the Avro Manchester and Blackburn B20. Rather than the chin radiator of the Griffon installation, it used a ventral "belly" radiator like the Hurricane.

Production.

Production of the 200 Henleys ordered ran from 1939 until mid-1940. The Gloster aircraft factory at Hucclecote / Brockworth that produced the Henley easily switched to producing Hurricanes in the Battle-of-Britain period and made a valuable contribution to the continuing supply of these much-needed fighters. Of course, the Hurricane then went on to be widely used as a fighter-bomber, often carrying bomb-loads equal to the Henley. After the Hurricane, the factory then produced the Typhoon, the outstanding fighter-bomber backbone of the British Second Tactical Air Force (2TAF) in the invasion of Europe.

The Henley production line at Hucclecote, with the Sea Gladiator production line in the background. This is about halfway through the Henley production run. L3330 had a varied service career, passing through the hands of various units, it ended its life in a cartwheel crash at Cleeve in March 1945.

A memo of a meeting in March 1942 , between the Air Ministry and Ministry of Aircraft Production, shows that restarting Henley production was considered at that time. It was foreseen that there would be a shortage of target tugs the following year and that the jigs for building Henleys had been kept in storage, so it would have been easy to restart the production line at Glosters, albeit at the loss of Hurricane and/or Typhoon output. Presumably, the Miles Martinet and Boulton Paul Defiant target tugs were able to plug the gap.

Hawker Henley target tug (probably L3243) on the Gloster airfield at Brockworth with the distinctive shape of Coopers hill (on the edge of the Cotswolds and famous for cheese-rolling) behind it.

The Hawker Henley described.

The Hawker Henley prototype, K5115,on display in the "new types" enclosure at the 1937 Hendon airshow with a de Havilland DH91 Albatross airliner in the background.

The Hawker Henley prototype, K5115,on display in the "new types" enclosure at the 1937 Hendon airshow with a de Havilland DH91 Albatross airliner in the background.

The prototype Hawker Henley (K5115) first flew on 10th March 1937 from the famous Brooklands aerodrome. It originally had struts to brace the tailplane and hinged plates to completely cover the main undercarriage wheels when retracted, both these features were later removed. At first, the prototype had one of the early trial Merlin "F" engines and fabric-covered outer wing sections like the early Hurricanes. It was later re-engined with a production Merlin I engine and given fully stressed-skin metal wings. The second Henley prototype (K7554) was completed as a target tug with a Merlin II engine and first flew on 26th May 1938. The first Henley prototype arrived for tested by the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (AAEE) at Martlesham Heath on January 10th 1938. This testing did show up some problems. It was hard for the crew to clamber onto the wing to get entry to the cockpit. Forward visibility, through the curved front canopy used on the prototype, was found to be easily obscured by rain or oil. These problems were cured on production aircraft by the fitting of a retractable step and a flat front windscreen. The top speed in level flight noted for this prototype was 292 mph at 17,100 ft (470 kph), while it was dived up to 395 mph (636 kph). Another production target-tug Henley was also tested late the same year and that was dived to 450 mph (724 kph) and pulled out at 6.4g without any structural damage. The Henley was a streamlined mid-wing monoplane, the mid-wing arrangement allowed the Henley to have a small bomb bay that could accommodate two 250 lb (113 kg) bombs side-by-side. There was provision for the rear gunner to adopt a prone position to use a bomb-sight in the floor of the aircraft for level-bombing (it seems to me from the cut-away drawings available that the "window" through which the bomb-sight operated was only uncovered when the bomb-bay doors were opened). While operating the bomb-sight the aircraft would be vulnerable from attack from behind while the gunner was out of reach of his gun. In the bomber version, this rearward firing gun would have been a .303 Lewis or Vickers "K" gun. The Henley was stressed for dive-bombing at angles up to 70 degrees, but there is no evidence of any arrangement for throwing the bombs in the bomb-bay clear of the propeller disk when dive-bombing at high angles (most dive-bombers used a bomb "crutch" to swing the bomb away from the fuselage on release). However, the prototype was tested with bombs under the wings, which would have been usable in dive-bombing. There was the provision, in the original bomber design, for a single browning .303 machine gun mounted in the starboard wing to fire forward, but because the outer wings were essentially the same as those used on Hurricane fighters there would probably have been little trouble in increasing it to two, four, six or even eight machine guns if required. In 1942, a Henley (L3276) was tested at Boscombe Down with two 500 lb bombs (227 kg), one under each wing, and also two "light series" bomb carriers, again one under each wing.

The prototype Henley (K5115) originally had a braced tailplane and hinged plates to completely cover the main wheels when retracted. Both features were later deleted from the prototype and never used on production Henleys.

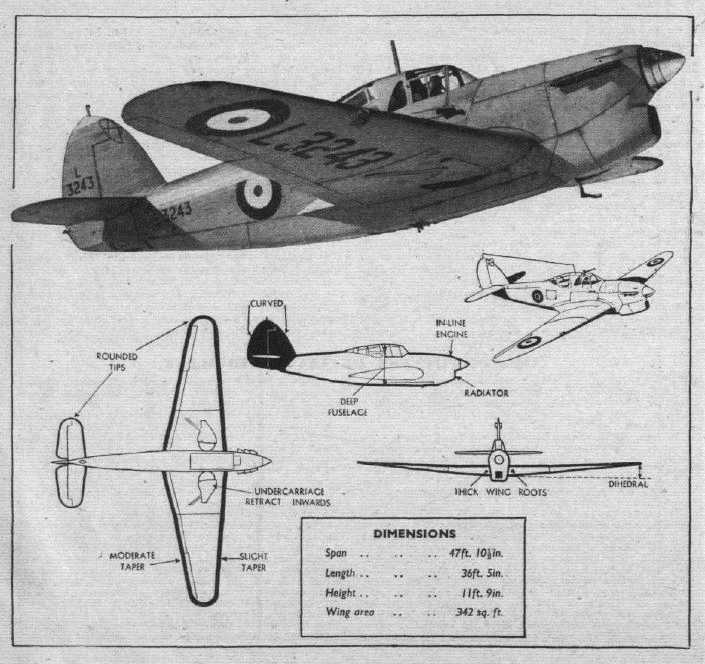

A wartime (1943) recognition diagram of the Hawker Henley.

Henley in action.

Henley L3357 pictured in what looks like a Royal Navy colour scheme with light grey undersides that extend up the side of the fuselage. Or are the undersides yellow? Henleys did serve with Royal Navy units, No 771 Squadron in the Orkneys and the Navy Co-operation unit at Gosport. But this particular Henley is listed as serving with No 1 Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit (1AACU) at Farnborough. It crashlanded near Bootle in Lancashire in July 1942.

Henley L3357 pictured in what looks like a Royal Navy colour scheme with light grey undersides that extend up the side of the fuselage. Or are the undersides yellow? Henleys did serve with Royal Navy units, No 771 Squadron in the Orkneys and the Navy Co-operation unit at Gosport. But this particular Henley is listed as serving with No 1 Anti-Aircraft Co-operation Unit (1AACU) at Farnborough. It crashlanded near Bootle in Lancashire in July 1942.

The Henley was never committed to action against the enemy as such, but operating in the war-torn skies of Britain during 1940 it was inevitable that some contact did occur. The two instances I'm aware of show up well the performance of the Henley. Sqdn Ldr D.H. "Nobby" Clarke wrote with feeling in his book "What Were They Like to Fly" about the potential of the Henley being wasted and he tells how he once used a Henley to catch up a fleeing Bf 109 over the English Channel and was able to get into a firing position but was unable to do anything because he had no guns. In the book "The Most Dangerous Enemy" by Stephen Bungay (an excellent history of the Battle of Britain) there is the story of Wing Commander Ira "Taffy" Jones, a veteran of WWI who was Station Commander of Stormy Down a small training airfield in South Wales. He took off in a Henley target tug to intercept a Junkers Ju 88 (fastest of the German twin-engined bombers of the time) that was flying over the Bristol channel. He closed on the Ju 88 and. having no other armament available fired a "Very" signal pistol at it, which caused it to turn tail and fly away.⁴

Ready for action.

Early in the war, damaged Henleys were repaired at the Cunliffe-Owen factory near Southampton. A video on YouTube shows a line of Henley fuselages in the bombed-out factory after a Luftwaffe raid in September 1940 (video at <this link>). Amazingly, it would seem all the Henleys involved were repaired and returned to service.

Some comments on the Henley.

"In many respects the Henley is an example of a highly efficient and promising aeroplane wasted."

- "Aircraft of the Fighting Powers" 1941 edition

"- I still think we could have done with a few Henley squadrons."

- Bill Gunston, War in the Air Magazine, July 1989.

" I trailed through the skies cursing them, my C.O. and all the lunatics who had relegated a war-worthy fighter to target-towing."

- Sqdn Ldr D.H. Clarke D.F.C. A.F.C. -"What Were They Like to Fly".

- "Aircraft of the Fighting Powers" 1941 edition

"- I still think we could have done with a few Henley squadrons."

- Bill Gunston, War in the Air Magazine, July 1989.

" I trailed through the skies cursing them, my C.O. and all the lunatics who had relegated a war-worthy fighter to target-towing."

- Sqdn Ldr D.H. Clarke D.F.C. A.F.C. -"What Were They Like to Fly".

Specifications

Engine: Production target tugs used either the Merlin II, Merlin III or Merlin V, these all gave 1,030 horsepower

Dimensions- Wingspan: 47ft 10 ½ inches (14.592 metres) Length: 36ft 5 ins (11.243 metres), Height: 14ft 7 ½ ins (4.46 metres)

Maximum speed (bomber configuration): at least 292 mph (470 kph). Target tug: 270 mph (435 kph) when towing a sleeve target.

Range: 940 miles (1,512 km).

Service Ceiling: 27,200 ft (8,290 metres).

Armament: Initially designed to have a single forward-firing Browning .303 gun in the starboard wing, a Vickers "K" or Lewis machine gun firing to the rear for defence, two 250 lb (113 Kg) bombs in the bomb bay and up to eight 24 lb (11 kg) bombs in racks under the wings (four each side). There seems to have been provision (in the prototype at least) for the bomb load to be carried under the wings instead. One Henley was tested with two 500 lb (227 kg) bombs, one under each wing.

Serial numbers: Prototypes K5115 and K7554. Production run L3243 to L3442 (200 aircraft). Serial numbers L3443 to L3642 were allocated for another 200 aircraft but this order was cancelled.

What-If Paintings

A painting of how Henleys might have appeared in the true dive bombing role - in this case over the bridges at Maastricht. This painting featured in Peter C. Smiths book "The History of Dive Bombing" (Pen and Sword 2007 edition).

Another painting showing how Henleys might have looked, attacking a German motorised column in France in 1940.

A Hawker Henley in desert camouflage colours circa 1942. The Henley might have been a very handy aircraft to have around in the Western Desert, which is where the RAF, at last, got to grips with the task of supporting the Army and developed the tactics later used in Italy and then France after D-day, including the formation of Tactical Air Forces (TAF). A mid-war (1942-43) Henley could have benefited from the increased power of the later Merlin engines, giving increased performance.

Hawker Henley painted as it might have appeared in Royal Navy service in early 1940. The Henley did serve in the Navy in the target tug role and some were supposedly on the airfield at Hatston in the Orkney Islands (with 771 Squadron) when Blackburn Skua dive-bombers took off from there to attack and sink the German Cruiser Königsberg anchored in Bergen harbour. The Skuas were operating at the limit of their range. The Henley had a range of 940 miles compared to the Skua's 760 miles, it could carry (potentially) twice the weight of bombs and its cruising speed was higher than the Skua's maximum speed! The Royal Navy operated Skuas out of Hatston against targets in Noway for much of 1940. One certainly wonders why the Henley was not used in this role instead.

Notes

¹ Contrary to popular myth, the Luftwaffe didn't do much direct support on the front line of the German army during the early war Blitzkrieg campaigns. They used their bombers (including the Stuka) for striking airfields, road and rail targets behind the front lines to blunt the enemy's response. They would concentrate their fighter forces over their advancing troops to stop strikes by Allied bombers. The YouTube video at <this link>, by the Military Aviation History channel, gives a good outline of Luftwaffe air support doctrine.

² Len Deighton in his book "Blitzkrieg - From the Rise of Hitler to the Fall of Dunkirk" makes just such a misleading assertion.

³ See Page 144 (chapter 6) of Colin Sinnott's "The RAF and Aircraft Design 1923-1939".

⁴ To see an article on "Taffy Jones" on the BBC website that mentions this incident <click here>.

Links

This web page on the Aviation Safety Network website lists all the known crashes of Hawker Henleys. Click on the individual dates for further information on each case. Note the number of cases of engine failure, the concentration of Henley activity in Cornwall and Wales and also the fact that the Henley continued to be used well into 1945. <click here>

Imperial War Museum colour film of a Henley target tug on exercises with the Royal Navy at <this link>. The Henley appears about 4 minutes into the film. The film also features a Blackburn Roc target tug.

Sources:

"Probe Probare" Part 16 by Alec Lumsden and Terry Heffernan in the September 1985 Edition of Aeroplane Monthly Magazine. 5 Pages with numerous photographs covers the testing of the Henley by AAEE at Martlesham Heath and Boscombe Down.

"What Were They Like to Fly" by Sqdn Ldr D.H. Clarke, Chapter 15 "Condemned at Birth!" covers the Henley (only 2½ pages). Published by Ian Allan in 1964.

"The Hawker Henley" by Thurstan James in the March 1st 1939 edition of "The Aeroplane" magazine is a 4-page article which includes a cutaway drawing and diagrams of the Henley's structure. This article was reprinted in the July 1989 (Issue 2) of "War in the Air" magazine.

"Hawker Aircraft Since 1920" by Francis K Mason, published by Putnam, ISBN 0 85177 839 9.

"The Secret Years - Flight Testing at Boscombe Down 1939-1945" by Tim Mason, published by Hikoki. ISBN 0 951899 9 5.

The Henley features in a number of articles in Air-Britain Aeromilitaria magazine. The most exhaustive are in the third (autumn) issue of 1975 and first (spring) issue of 1992, listing the known fates of all Henleys and a list of units they served with. Issue 2 (summer) of 1983 contain a shorter article concentrating on L3243.