Dinger's Aviation Pages

BLACKBURN B20

My thanks to Bill Watson for providing much of the information on this page and for the pictures of his team raising one of the engines.

This page is dedicated to the memory of Flt Lt Henry "Harry" Bailey, Duncan Robertson, and Sam McMillan.

This page is dedicated to the memory of Flt Lt Henry "Harry" Bailey, Duncan Robertson, and Sam McMillan.

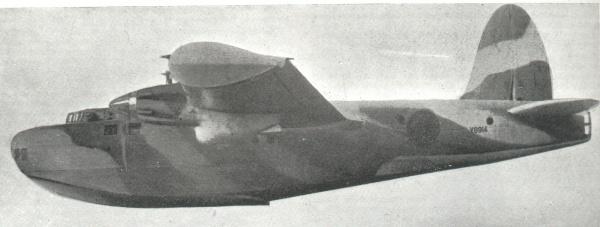

The Blackburn B20. It is likely to be a composite image, airbrushed to show the B20 as it would have appeared in flight.

The Blackburn B20 is one of the least known British aircraft designs of the Second World War. Although the project was abandoned in 1940 its existence was kept hidden until June 1945. What was so special about this aeroplane to warrant this level of secrecy?

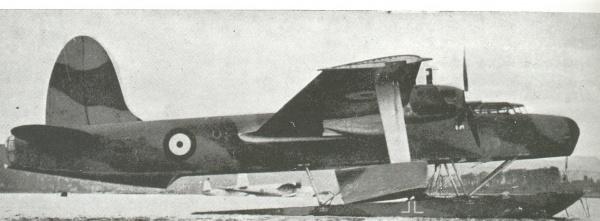

Blackburn B20 at anchor.

Between the World Wars, the design of flying boats proceeded at a fantastic pace. By the mid-1930s giant four-engined flying boats such as the Shorts "C" class and the Boeing Clipper were on the drawing board. The need to keep the propellers clear of the water meant that such designs had deep fuselages, far from streamlined. One way around this problem was to mount the wings and engines high above the fuselage on a pylon or struts, such as in the Consolidated Catalina and Dornier Wal designs, but such installations still produced drag. In 1936 Major J.D. Rennie, chief seaplane designer for the Blackburn Aircraft Company put forward a revolutionary design to meet Air Ministry Specification R1/36. His radical idea (UK patent number 433925) was to have the entire bottom of the flying boat hull able to be extended downwards for landing and be retracted for flight, giving a slim streamlined fuselage and the promise of unprecedented speed for a flying boat. It should be noted that a similar concept had been used in the experimental Ursinus floatplane of 1916, built by Oskar Ursinus. Before designing the retracting-bottom flying boat Blackburn had built and flown the Sydney flying boat, with a pylon and strutted parasol wing that was very close in configuration to the later Consolidated Catalina. But being some five years earlier, the Sydney did not benefit from the development of more efficient Alclad construction and the more powerful engines available to the Catalina.

The earlier Blackburn RB2 Sydney flying boat. Built to a 1927 specification (R5/27), its wings had a duralumin structure covered in fabric, except for metal walkways next to the engines. The heavy weight of the thick wing meant it had a marginal performance and the single prototype suffered from bad serviceability during testing. It first flew in July 1930.

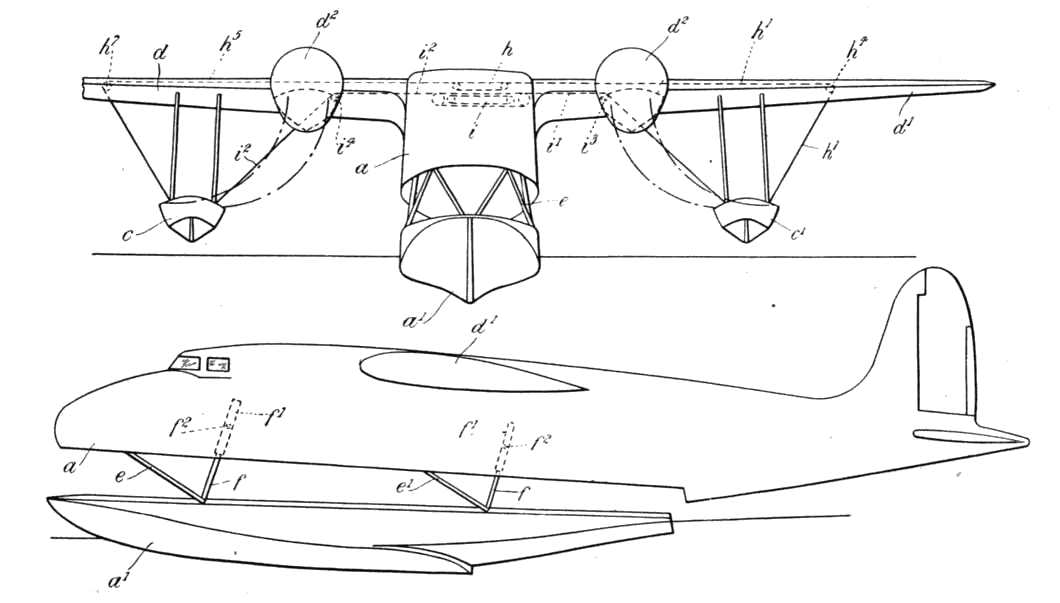

The diagram for J.D. Rennie's patent for a retractable bottom for a flying boat (patent number 433925). Note that at this stage it was envisaged that the wing floats would retract into the rear of the engine nacelles.

Major John Douglas Rennie, Chief flying boat designer for the Blackburn Aircraft company and designer of the B20.

Major John Douglas Rennie, Chief flying boat designer for the Blackburn Aircraft company and designer of the B20.

At the time the B20 was being developed, Blackburn had a parallel project to produce a two or three-seat twin-engined aircraft for the Royal Navy (presumed to be for Air Ministry Specification S9/36). Diagrams for such a design labelled as the "Blackburn BB5" are in the Blackburn archive. Powered by two small Bristol Aquila engines, the design, about the size of an Airspeed Oxford, features much the same retractable bottom as the B20 but with the addition of an undercarriage that retracted into the rear of the engine nacelles; enabling it to be used as both a flying boat or directly from aircraft carriers. It also featured a low-profile, remotely controlled turret with four machine guns. This conformed to the Navy's doctrine at the time. The design seems to have never been formally tendered to the Air Ministry.

Above is a sketch of the Blackburn BB5 project for a small retracting-bottom amphibian flying boat, as found in the Blackburn archive.

Three companies tendered designs for R1/36, along with the Blackburn proposal Saro and Supermarine both put forward projects (the Supermarine type 314 tendered was one of the last design projects RJ Mitchell had a hand in). The Air Ministry chose the Saro S36 Lerwick to meet specification R1/36 (the Lerwick proved an expensive failure, seeing only limited service and only 21 were produced) but was sufficiently impressed with the Blackburn design to authorise the building of two prototypes. It was originally intended to use two Bristol Hercules engines, but as design and construction commenced the design weight of the aircraft grew and it became obvious that to fully realise the high-speed potential of the B20 more powerful engines were needed. The only choice available was the Rolls-Royce Vulture 24-cylinder engine of 1,700 hp.

The Blackburn B20 on the Clyde at Dumbarton.

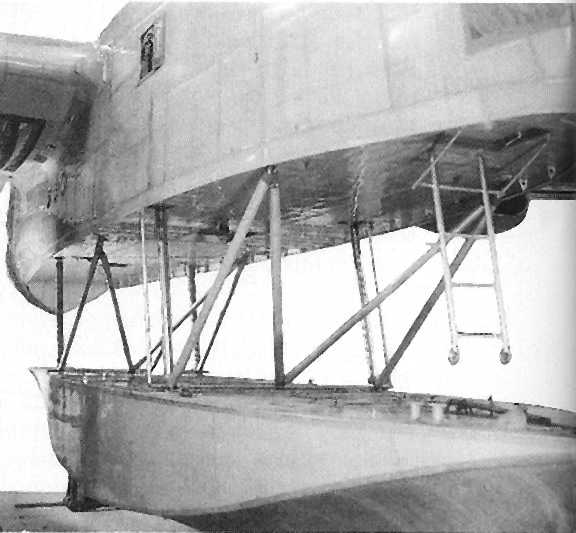

Construction of the prototype B20 began at Blackburn's new flying-boat production facility at Dumbarton in 1937. The biggest technical problem to overcome was to ensure that the retracting bottom went up and down at a constant rate with no difference between the forward and rear struts. This process was complicated by the weight of fuel (5,700 lb, 2.585 Kg) that was stored in the central pontoon float. The British division of Lockheed produced a hydraulic system that operated at a high pressure (2,450 psi) to do this. It could retract and extend the pontoon in flight, or do the same when the aircraft was on the water to enable easier servicing. It had provision for emergency extension in flight by gravity, in case of failure of the hydraulic system. The retracting wingtip floats could be operated separately from the central pontoon, the procedure was to retract the wingtip floats shortly after takeoff and then retract the central pontoon once the wingtip floats were up. Each wingtip float could be retracted separately from the other to help with servicing.

Rear view of the B20, showing the dummy turret.

The B20 had a nose position for a bomb aimer with a flat glass panel for the bombsight and windows on the sides for observation. The pilot and co-pilot sat side-by-side in a spacious flight deck with two escape hatches in the roof. Behind and lower was a cabin for the navigator, radio operator and flight engineer, they had large windows on either side. Behind that and under the wing spars was a cabin with a couple of bunks for the crew to get a rest on long missions. To the rear of that was a cabin with a galley to prepare food and drink, a workbench and tools and an Elsan "thunderbox" chemical toilet. On the prototype, a dummy turret was fitted at the rear of the fuselage. On production aircraft, it had been planned that a four-gun tail turret would have been fitted along with a two-gun dorsal turret in the roof of the rear fuselage. There would also have been two machine guns positioned in the nose somehow. There was provision in the design for the carriage of four 500 lb (227 kg) bombs, two in each wing in cells inboard of the engine nacelles. The doors of the cells were designed to open inward to reduce drag. The wing had three spars and was constructed as a single unit. General construction was of Duralumin and Alclad with special consideration given to flush-riveting to reduce drag. Control surfaces were fabric-covered.

When war broke out in 1939, the second prototype was cancelled and any chance of a production order was lost, factory resources were devoted to types already in production (Blackburn built Short Sunderland flying boats) and Consolidated Catalinas were purchased from the USA. This is understandable, since at the time the pressing need was for aircraft to patrol the Atlantic approaches and seek out U-boats, the high speed of the B20 was simply not seen as an advantage. If you had told anyone in Coastal Command or the Admiralty that by mid-1940 the Atlantic seaboard from the far north of Norway to the Bay of Biscay would be in Nazi hands and used as bases for long-range FW Condor patrol aircraft and Ju88 long-range fighters you would have been laughed at!

On the water, B20 prototype V8914 showing retracting wingtip floats. Mooring could be done from the deck of the retractable pontoon.

However, there was little doubt that the single B20 prototype nearing completion (serial number V8914) showed great promise and so flight trials were allowed to go ahead to glean data for future designs. It was nicknamed the "nutcracker", referring to the fate of anyone on the central float when it was retracted. The B20 took to the air in March 1940, flying from the Blackburn factory at Dumbarton on the Clyde.

Two different accounts of the testing process are recorded and they differ in some key matters (see notes¹ and sources below). One thing they do agree on was that the ability to stand on the float "pontoon" made the B20 very much easier to moor and board than a normal flying boat. According to one account by Ivan Waller a Rolls-Royce engineer, on the first flight, it was found that there was a problem with the aileron trim and it took four or five more test flights to sort this out. According to this account, there were no trim tabs on the ailerons and alterations could only be done on the ground (although photos and diagrams do seem to show aileron trim tabs). In the process it had a birdstrike and repairs had to be carried out. According to the other account, by Fred Weeks a Blackburn flight-test engineer, the first three flights were little more than "hops" off the water, with no mention of a birdstrike, with a proper flight with retraction of the pontoon not taking place until the 4th flight on April 4th 1940.

The B20 pontoon, showing the ladder to gain entrance. There were another two hatches in the "floor" of the aircraft to allow escape onto the pontoon in an emergency. Mooring equipment (boat hooks and anchors) was stored under panels in the pontoon. The fuel tanks were accommodated in the centre of the pontoon which made fuel replenishment much simpler than on a traditional flying boat.

On the 7th of April 1940, the day before German forces invaded Denmark and Norway, the B20 took to the air from the River Clyde at Dumbarton for its first attempt at a high-speed run. According to Fred Week's account, this was only the aircraft's 5th flight and only the second time the pontoon had been retracted in flight. If this is the case, it seems somewhat foolhardy to do a high-speed run so soon in the test programme. The pilot was Blackburn's test pilot Flt Lt Henry "Harry" Bailey, with him were Ivan Mark Waller the Rolls-Royce flight test engineer, Fred Weeks the Blackburn flight test engineer together with Duncan McNaught Robertson and Samuel McMillan both Blackburn aircraft riggers along to monitor instruments during the flight. The flight that day was over the Firth of Clyde and Sound of Bute on Scotland's west coast. The high-speed run took place; according to Waller's account, an astonishing speed of 345 mph was reached. According to Weeks, a more modest (but still impressive) top speed of 285mph was recorded. But shortly afterwards severe vibration set in. Reducing speed did not help and Flt Lt Bailey ordered the crew to take to their parachutes. Up in the cockpit, Ivan Waller was first to try to get out using the escape hatch above the co-pilot's seat (Waller had been sitting in the co-pilot's position). However, in the attempt, his parachute deployed too early and became caught in the wireless aerial mast on top of the fuselage with Waller only halfway out of the hatch. Fred Weeks was able to get out of the other escape hatch in the roof but he hit the aircraft's rudder ² before his chute opened. Then the vibration stopped and Ivan Waller was able to climb along the top of the fuselage to untangle his parachute before a sudden lurch of the aircraft threw him off. Flt Lt Bailey stayed with the aircraft until the last possible moment to give the other two crew members a chance to escape, his parachute did not open fully and he drowned. No trace was ever found of Duncan Robertson and Sam McMillan. The two surviving crew members, Weeks and Waller, were rescued after some 15 minutes in the cold sea by the improbable-sounding HMS Transylvania (a converted merchant ship). The crew of the Transylvania reported seeing a large rectangular unit come down out of the thick cloud cover, probably an aileron. The most likely explanation for the crash is that the initial vibration was aileron flutter, this ceased when the aileron broke free (giving Ivan Waller his chance to free his parachute). But with the loss of an aileron, the aircraft would have been uncontrollable, leading to its crash. With the loss of the one-and-only example of the B20 the project ended. However, a development called the B40 was planned and the Saro company designed a large 4-engined flying boat that incorporated Blackburn's retracting-bottom technology (The Saro S39A). Neither got beyond being a paper project.

Flt Lt Henry "Harry" Bailey, A.M.I.C.E., A.F.R.Ae.S, pilot of the B20, who lost his life in the crash.

The 3 images above are of the B20 prototype V8914 at the Blackburn Factory in Dumbarton (in the top photo you can see the famous "Rock of Dumbarton" on the left). The photos are courtesy of Patrick Tilley.

The picture above is of the Saro Lerwick which won the order for specification R1/36. Its dumpy, high-sided fuselage shows exactly the problem of drag the retracting bottom of the B20 was designed to avoid. Note that the front turret had to slide back to allow mooring duties to be carried out (as in the Sunderland). The B20 design allowed these to be carried out from the "deck" of the retracting pontoon bottom.

Specification

Volume 6 of "Aircraft of the Fighting Powers", published in 1945, gave the following figures for the Blackburn B20 (the same figures are in "Jane's All the World's Aircraft" for 1945).

Span: 82 ft (24.9 m). Length: 69 ft 8 ins (21.1 m). Height on beaching trolly with pontoon lowered: 25ft 2 ins (7.6 m).

Weight loaded: 35,000 lb (15,090 kg).

Tankage (normal): 590 gallons (2,714 litres). Maximum: 976 gallons (4,489 litres).

Estimated performance in recce configuration (without turrets) . Max level speed at 15,000 ft (4,560 m) : 322 mph (515 kph).

Estimated performance with turret armament: Max level speed at 15,000 ft (4,560 m) : 306 mph (489 kph).

Projected armament: two .303 machine guns in the nose, two .303 guns in a dorsal turret, four .303 machine guns in a tail turret. Four 500 lb (227 kg) bombs in cells in the inner wings.

Specification

Volume 6 of "Aircraft of the Fighting Powers", published in 1945, gave the following figures for the Blackburn B20 (the same figures are in "Jane's All the World's Aircraft" for 1945).

Span: 82 ft (24.9 m). Length: 69 ft 8 ins (21.1 m). Height on beaching trolly with pontoon lowered: 25ft 2 ins (7.6 m).

Weight loaded: 35,000 lb (15,090 kg).

Tankage (normal): 590 gallons (2,714 litres). Maximum: 976 gallons (4,489 litres).

Estimated performance in recce configuration (without turrets) . Max level speed at 15,000 ft (4,560 m) : 322 mph (515 kph).

Estimated performance with turret armament: Max level speed at 15,000 ft (4,560 m) : 306 mph (489 kph).

Projected armament: two .303 machine guns in the nose, two .303 guns in a dorsal turret, four .303 machine guns in a tail turret. Four 500 lb (227 kg) bombs in cells in the inner wings.

Project Doomed Anyway?

In an article in Issue 35 of "The Aviation Historian" magazine (April 2021), Matt Bearman reasons that the problems with the Vulture engine used on the Manchester bomber were mostly caused by airflow on the propellers reaching transonic speeds and the action of the constant-speed hydromatic propellers then causing a loss of power, limiting the top speed of the aircraft and ultimately damaging the engines. The same problem might be expected for the Blackburn B20, meaning it would never have been able to attain the high speeds expected of it. The same issue is suspected to be behind the poor performance of the Hercules engines on the Saro Lerwick, with its large-diameter propellers and their hydromatic constant-speed mechanism. If the B20 had been fitted with Hercules engines (as originally planned) then again, a reduced top-speed and constant engine problems would be anticipated. The issue of supersonic drag on propellers was simply not widely understood at the time; if it had been, the adoption of thinner profile blades might have solved most of the issues of the Vulture and Peregrine engines and given better performance to the Hercules when fitted to the Lerwick, Beaufighter and Albermarle. Anyone interested in British aircraft development in the 1930s and 40s is strongly advised to read Matt Bearman's article.

What if?

If the Blackburn B20 had been chosen instead of the Saro Lerwick it is likely there would have been tremendous pressure to use the Hercules engines as originally planned. In this case, J.D. Rennie would either have had to resist the growth in the weight of the B20 during its development or accepted a reduced performance in either speed or range. However, the Hercules engine was developed extensively both before, during and after the war and its power was increased from 1,150 horsepower of the MkI in 1936 through the 1,615 horsepower Mk VI of 1941 to the 2,080 horsepower Mk 762 of post-war years. So mid to late-war versions of a B20 powered by Hercules engines could well have come close to realising the full speed potential of the airframe (assuming the propeller issues outlined above had been solved). If the B20 had been chosen to meet R1/36 it would have had an armament of 8 machine guns (2 in the nose, 2 in a dorsal turret and 4 in the tail turret) and carried a bomb load of 2,000 lb (the B20 was designed with 4 bomb-cells in the inner wings, each capable of accommodating a 500 lb bomb). The range called for in R1/36 was only 1,500 miles (The Sunderland and Catalina flying boats both had a range of more than 2,500 miles).

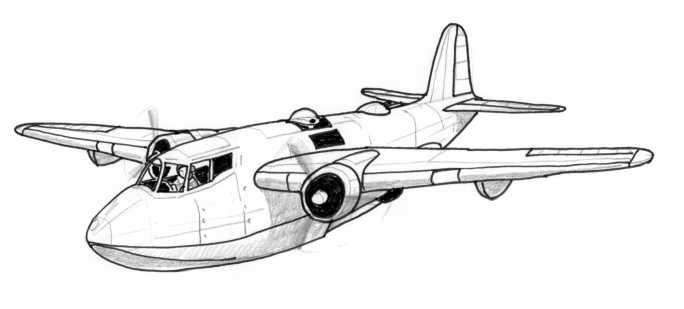

How a Hercules powered version of the Blackburn B20 might have looked.

If, on the other hand, the B20 had been ordered into production later, after the switch to Rolls-Royce Vulture engines as the powerplants, an alternative engine would have been needed when production of the Vulture was stopped. One way forward would have been to emulate the process which transformed the Avro Manchester into the Lancaster and replace the two Vultures with four Merlins. Another solution, as adopted for the Vickers Warwick bomber, was to wait for the availability of the 2,300 horsepower Bristol Centaurus late in the war. Taking a real broad overview, perhaps the best engines for the B20 would have been the Fairey P-24 "Monarch" engine of 2,240 horsepower (hoped to be developed to 3,000 hp) which was flying in prototype form in 1939 but was cancelled by an Air Ministry that thought Britain had too many aero-engine companies. Each Monarch engine consisted of two12-cylinder units, each of which drove its own contra-rotating propeller, a mechanically simple arrangement which avoided the many problems which plagued the outwardly similar German Daimler-Benz DB606.

How the B20 might have looked in the air-sea rescue role. Its speed would have made its chance of survival in this task over the North Sea much greater than the types which actually carried it out. The pontoon float would have greatly simplified the task of picking up survivors.

Would the B20 have been a success if it had gone into service? A biography of Wilfrid Freeman³, the man ultimately responsible for the cancellation of the B20 project, says "the operational requirement for a heavy flying boat with a top speed of 340 mph was questionable". Maybe so, and of course, none of the Blackburn designs of the war years was particularly liked by their crews (the Botha in particular). The B20 would not have had the range to hunt U-boats in the mid-Atlantic. However, I bet there were a lot of Coastal Command aircrew that would have given their right arm for an aircraft able to outrun the long-range Junkers 88 fighters over the Bay of Biscay or off the coast of Norway. The B20 would have been able to catch and shoot down any FW Condors it encountered. It would also have been of immense use for reconnaissance in the Mediterranean and Far East (the actions in defence of Ceylon in 1942 spring to mind). Imagine a B20 in 1943/44 capable of over 300 mph with a 57 mm Mollins gun in the nose and rocket projectiles under its wings, now that would have been a powerful weapon!

One thing that should be remembered is that after the B20 was rejected for the R1/36 specification its development from that time was as a flying test bed for the retractable bottom technology. If the Second World war had not occurred it is likely that the two B20 prototypes planned would have taken to the air in civilian markings and that Blackburn would have worked to adapt the B20 into a fast flying boat airliner, and its extra speed in that role may well have appealed to many passengers in the aviation marketplace. Just think of a trip in a fast Blackburn flying boat from Southampton down to the posh resorts of Biarritz, Monte Carlo and Capri in a 1940s Europe free of war and dictatorship.

Recovery

On 28th August 1998, Royal Navy divers recovered one of the Rolls Royce Vulture II engines of the Blackburn B20 prototype from the sea. The wreck itself is a war grave but a fishing trawler's nets had become entangled in the engine and dragged it into shallower water. Because of the rarity of the engine, it was decided to raise it. The propeller was separated from the engine and each part was floated to the surface by airbags from where they were hoisted onto HMS Damant. The following pictures were sent to me by Bill Watson who took part in the recovery.

From the view above the engine looks like a radial, an optical illusion caused by viewing it from the front. What you are seeing are the steel piston liners of the "X" arrangement Vulture Mk II engine. With the aluminium engine blocks rotted away, they are flopping around the steel crankshaft and have fallen into a circular arrangement. See the photo of the recovered engine in the museum for a better perspective.

Joe McGrath informed me the engine was displayed for a time at the Rolls Royce Museum at Hillington in Glasgow until the museum closed. In Sept 2007 I received an email from Jim Richardson to saying that the engine is now on display at the Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Museum near Dumfries. I visited it myself in 2012, All the aluminium parts have disintegrated leaving only part of the steel crankshaft with a few steel piston liners attached. They are liberally painted in black and silver to prevent further corrosion. The item is displayed in a lean-to on one side of the site.

The remains of the Rolls-Royce Vulture engine at the Dumfries and Galloway Aviation Museum in 2012.

Notes:

¹ The two articles that give different perspectives on the Blackburn B20 flight-test programme and crash are "Flight of the Nutcracker" by Peter Harding, which is based on Ivan Waller's memories of the events and "The Blackburn B20" an article by Derek James based on the memories of Fred Weeks (see sources below).

² In July 2002 I received an email from Richard Weeks, son of Fred Weeks. He said his father never forgot his experience and carried a metal splint in his leg from the rudder he hit on the way out. Fred Weeks died in 1977. The "Caterpillar Club" badge, given to Fred Weeks for using an Irving parachute, was featured in an episode of the BBC's "Antiques Roadshow" television programme (Series 43 Newby Hall, first broadcast on 18th April 2021).

³ Quoted from "Wilfred Freeman - The Genius behind Allied Survival and Air Supremacy 1939 To 1940" By Anthony Furse. ISBN 1-86227-079 - 1.

Sources:

The Blackburn B20 - an article by Derek N. James in the February 1974 edition of Aircraft Illustrated magazine. Fred Weeks' memories of the events of the crash are featured.

Flight of the Nutcracker - an article by Peter Harding (reminiscences of Ivan Waller) relayed to me by Bill Watson.

Air Britain Aeromilitaria Magazine Volume 33 Issue 130 Summer 2007 - Article "Blackburn B20, B40 and B44"

British Secret Projects- Fighters & Bombers 1935-1950 - by Tony Butler, Midland Publishing 2004 ISBN 1 85780 179 2.

The British Aircraft Specification File - KJ Meekcoms & EB Morgan, Air-Britain Publications 1994 ISBN 0 85130 220 3

Blackburn Aircraft since 1909 - by AJ Jackson published by Putnam ISBN 370 000536

Jane's All The Worlds Aircraft 1945 Collectors Edition - ISBN 000 470831-8

Links:

Please note this webpage had a major rewrite in December 2022.