Dinger's Aviation Pages

RJ MITCHELL

A short biography of Reginald Joseph Mitchell, designer of the Spitfire

R.J. Mitchell was born on the 20th May 1895 at 115 Congleton Road, Talke, Stoke-on-Trent in the Potteries area of England, famous for its ceramics. His parents were both teachers (although his father later started his own printing business). R.J. had three brothers and two sisters. At school, he showed a flair for both maths and art (his youngest brother, George William Mitchell "Billy", was a very accomplished artist, founding a ceramic transfer company in Stoke on Trent, designing patterns and various imagery for Royal Crown Derby, Minton, Spode, and lots of other top companies) but the young Reginald`s first love was engineering. In 1911 he was apprenticed to a firm of railway locomotive makers in Stoke-on-Trent. As part of his apprenticeship, he attended night school where his flair for mathematics was particularly evident. In 1917 he made the bold move to Supermarine in Southampton.

The following year he married Florence Dayson, who was some 11 years older than he and had the well-paid and responsible job of Headmistress of an infant's school back in the Potteries. One can only wonder what qualities the young RJ Mitchell must have had for Florence to give up her job and marry a man only a year out of his apprenticeship.

Supermarine had started as Pemberton-Billing Ltd in 1913. Under the control of its founder, Noel Pemberton Billing, it had been generally unsuccessful with its projects but had managed to survive by doing sub-contracted production of other company's designs and with experimental and repair work. In late 1916 control of the company had passed to Hubert Scott-Paine, who renamed it the Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd (until then the word "Supermarine" had only been used as a tradename). Under Scott-Paine the company began to prosper by producing seaplanes designed by the "Air Department" of the Admiralty (the so-called "A.D" boats). R.J. Mitchell seems to have started as Scott-Paine's assistant, but he must have impressed his new boss, for by 1920, at the age of just 25, he was the firm's chief designer. His initial work was in refining the "AD" designs, something he did with great success.

Between 1920 and 1936 he designed 24 different aircraft ranging from light aircraft and fighters to huge flying boats and bombers. This remarkable output in only 16 years is what sets him apart from other aircraft designers. Part of Mitchell's genius was his ability to get an aircraft to a certain point in development and then hand responsibility to others, it was only in this way that he achieved his prodigious output. When Supermarine was taken over as part of Vickers Ltd in 1928 it was written into the contract that Mitchell should stay with the company for at least 5 years, such was his reputation. At first, Vickers tried to get Mitchell to cooperate with one of their "own" top designers. Mitchell had other ideas and would always walk out of the room when the other designer walked in. Soon Vickers relented and let the Supermarine design team carry on working as before, and their designer went back to Vickers proper. His name? - Barnes Wallis of Wellington bomber and bouncing bomb fame! Under Mitchell's guidance, Supermarine was one of the few British aircraft companies able to run at a profit during the lean years of the stock-market crash and the following economic depression. They did this despite employing a higher proportion of skilled men than their competitors.

Mitchell had a mixture of qualities. With people he did not know, he often appeared shy. A slight stammer added to this impression and seemed to have caused him real distress when called upon to give speeches. However, on his own ground within Supermarine, and with people he knew, he was a supremely able and confident manager who would not suffer fools gladly. He was a very good listener, who would let even the most junior draughtsman have their say in the complex job of designing aircraft. He would always take full responsibility for the project as a whole, never letting his staff be criticised by anyone but himself. Over and again people said he was a man who could take a long time thinking over a problem (people soon learnt not to interrupt him when he was thinking) but who would then be galvanised into action once he had come up with a solution to any design problem.

Mitchell was particularly interested in safety and all his machines were above all safe to fly and to land. Only two exceptions come to mind, the wing flutter of the Supermarine S4 which would have been impossible to predict with the design tools available then*, and the Supermarine Air Yacht, which was somewhat underpowered. This safety record is particularly striking if you compare it with many other aircraft companies of the time developing similar "cutting-edge" aircraft (Messerschmitt (Bf) in particular had an awful safety record over the same period). Mitchell was one of the few aircraft designers of the day who learnt to fly himself, albeit late in his life.

The most commercially successful of Mitchell's designs in the '20s and early '30s were the big Southampton and Stranraer flying boats for the RAF. It was these designs that kept the Supermarine company going through the economic depression.

The Supermarine S4.

Mitchell was responsible for the Schneider-winning seaplanes developed by Supermarine up until 1931. His S4 design of 1925 was years ahead of its time - perhaps a little too advanced! His later S5 and S6 racers were a little less radical (having wire bracing for the wings). As one of Britain's premier seaplane builders, it was only natural that Supermarine should have competed in the contest but the lessons learnt were hard to apply to civil aviation projects. So Supermarine produced tenders and designs for the Air Ministry Specifications for fighters for the Royal Air Force. Speed is a prime consideration in any fighter and Mitchell's experience with high-speed floatplanes made him well-placed to meet the needs of the RAF.

In October 1931 the Air Ministry issued the delayed specification F7/30 calling for a new fighter armed with four machine guns. In response, Mitchell designed the type 224, a strange-looking aircraft with a fixed undercarriage housed in "trouser" fairings, mounted on an inverted gull monoplane wing. The Type 224 had a metal, stressed skin fuselage but it lacked flaps or an enclosed canopy and the rear parts of the wing were fabric-covered. It was powered by a 660 horsepower Goshawk engine giving a top speed of 228 mph. The gull-wing layout was an essential element of the design, steam from the steam-cooled Goshawk engine would condense in the wing leading edge and the water would then be collected in tanks in the undercarriage "trousers". The design showed no advantage in performance over the more traditional offerings of other companies, and without the benefit of flaps, it must have had a high landing speed, a handicap in an aircraft that had to be able to be landed safely at night (F7/30 called for an aircraft that could function as both a day and night fighter). In fact, the Type 224 had an inferior performance to the Gloster Gauntlet biplane fighter that was just then coming into service with the RAF.

Supermarine Type 224.

A medical check-up before a family holiday led to Mitchell being diagnosed to have cancer of the rectum and in August 1933 he had a colostomy. In the 1930s this operation, with its unpleasant side effects would normally leave people housebound. Mitchell could probably have simply retired at this point, or arranged to work from home, but that was not the sort of person he was. He went back to work with his colostomy bag strapped to his side. If anything it seems to have galvanised Mitchell into even greater efforts at work and play. He started flying lessons in December 1933 and got his pilot's licence in July 1934, making his first solo flight in a Tiger Moth. Mitchell is remembered as the designer of the Spitfire, but he also deserves to be remembered as a shining example to cancer sufferers of how you can carry on without fear of embarrassment or indignity.

Even before the Type 224 was rejected for the F7/30 specification he began work on a new project, the Type 300, which would become the Spitfire. It was intended to use the Goshawk engine. So again the design included a strong metal leading edge in front of the wing spar to act as the condensation tank for the steam cooling. When the new Rolls-Royce PV12 engine (later to become the Merlin) was substituted, the strong metal leading edge was retained because the Merlin was originally envisaged as having steam cooling like the Goshawk (albeit with a small backup radiator). After the first few Mk A and B Merlins used this composite cooling system the Mk C and all subsequent Merlins switched to an all-liquid system. This used Ethylene Glycol, which transferred heat better than water and hence meant the radiators could be made smaller. The strong leading edge structure of the Spitfire's wing was no longer needed as a condenser tank, but it was retained. Out of such fluke design evolutions was the classic Spitfire wing developed, the key to the aircraft's success. The wing was extremely strong, having a central spar made up of hollow sections that slotted into each other. The result was not unlike a leaf spring, providing great resilience. The metal leading edge "box" in front of the spar added to this strength. The wheels retracted outwards into the wing, meaning the undercarriage mechanism could be put in the thickest part of the wing, this kept the wing thin. The undercarriage retracted into bays to the rear of the wing spar meaning the structural integrity of the spar-leading edge "box" was not impaired. As if this was not enough the wings incorporated "wash-out" meaning the angle to the airflow was slightly greater near the fuselage than at the tip. It meant the pilot got plenty of warning of a stall, as the aircraft would start to "talk" to the pilot through feedback to the controls. This is particularly important in combat as in a tight turn the aircraft needs to be kept just on the "edge" of stalling to get the minimum turning circle. The Spitfire's wing turned out to be capable of withstanding very high "Mach" numbers. In fact, the wing's performance at high speed was better than the wings designed for the early jet fighters ten years later!

The design work was well advanced when the RAF asked for an armament of eight machine guns in all-new fighter aircraft (this change is often credited to Sqdn Ldr Ralph Sorley but Colin Sinnott in his book "The RAF and Aircraft Design 1923-1939" shows that the RAF was calling for 6 or 8 guns in fighters well before Sorley joined the Air Staff). Over at the Hawker aircraft company, Sydney Camm, who was designing the Hurricane, had no problems fitting the guns close together in the thick wing of the Hawker fighter. However, Mitchell wanted to keep the Spitfire's wings as thin as possible. To do this and accommodate not only the guns but also their ammunition boxes, the guns had to be spread out along the wing. Mitchell had adopted an elliptical wing plan for his new aircraft, and this proved capable of holding four machine guns in each wing rather than the two it was originally envisioned as taking.

Mitchell gave the Type 300 a monocoque fuselage, which meant that the interior was unobstructed by bracing struts or wires. This was in contrast to the Hurricane, which had a fuselage constructed like a fabric-covered biplane. The space inside the Spitfire was put to good use in photo-recce Spitfires where large cameras were mounted behind the pilot pointing downwards and to the side.

The Spitfire's fuel tanks were mounted between the engine and the pilot. The Spitfire was initially not designed to carry fuel in the wings, and fuel was only put in the wings for long-range reconnaissance Spitfires (at the expense of armament) or in later war models. Although Spitfire reconnaissance aircraft such as the PR Mk VI, PR IV, PR Mk X and Mk XI could fly to Berlin and back, the Spitfire fighter versions were always restricted to a short-range. The Allies had to wait for the later Mustang and Thunderbolt before they had fighters that had a range of 1,000 miles or more.

Vickers's attitude to allowing Supermarine to develop the Spitfire is particularly admirable when it is remembered that Vickers itself had spent lots of time and money on its own single-engine fighters the "Jockey" and then the "Venom", which was still very much in with a chance of winning Air Ministry production orders when the Spitfire design was first started. A myth has grown up that the Air Ministry showed little interest in the Type 300 Spitfire. In fact, they seem to have welcomed the Type 300 Spitfire development very early on, even before the Type 224 had been rejected for F7/30. At first, they regarded the Spitfire as a "high-speed technology demonstrator" which would push forward aircraft design, but it quickly became apparent that the new aircraft would be suitable for production as a front-line fighter. The Air Ministry wrote Specification F10/35 around the Spitfire and considerably reduced their normal requirements for fuel capacity and range to comply with the Supermarine design. The Air Ministry even put up the money for the building of the prototype.

Mitchell devoted most of 1935 to work on the Spitfire. Two people on the design team deserve special mention; Beverly Shenstone a Canadian aerodynamicist did the outstanding wing design and Alfred Faddy did much of the detailed design work. The naming of the new aeroplane was done by the directors of Supermarine. For a time they were thinking of calling it the "Shrew". However, in the end, they decided to keep the name given originally to the Type 224, the SPITFIRE. Mitchell's Sister in law Elsie remembers him saying, "Bloody silly sort of a name."

Supermarine Spitfire

The Spitfire prototype, with the serial number K5054, first flew from what is now Southampton airport on the 5th of March 1936. Piloted by "Mutt" Summers, it was reported to handle beautifully. In later tests, it reached 349 mph. There was no doubt that Mitchell had delivered the goods. Even before the prototype had completed its official trials the RAF ordered 310 Spitfires, the success of Mitchell's design was assured.

The era of the monoplane piston-engined fighter lasted only some 15 years, from about 1935 to 1950. The Spitfire was unique in that it was the only aircraft to span this whole period and stay "the best". This is the true mark of Mitchell's Genius.

Mitchell's other outstanding designs were the Walrus amphibian, which built itself a reputation for ruggedness in the air-sea rescue role and the earlier Southampton and Stranraer flying boats. One design that was often in the news in the early thirties was the "Air Yacht", a flying boat for the wealthy to "cruise" between the fashionable French and Italian coastal resorts. It is also interesting to look at one design that never got into the air; the Supermarine bomber. In designing the Spitfire Mitchell had pioneered a unique method of wing construction, the single spar with a thick metal leading edge. If this leading-edge section could be filled with fuel it promised an aircraft with a very thin wing and slim aerodynamic fuselage while still having a large fuel capacity. The Supermarine Bomber (project B12/36) would have carried a bomb load almost as great as the Lancaster at greater heights and at a speed close to that of the Spitfire! In short, the B12/36 could have given the RAF a bomber superior to every other W.W.II type except the B29 Superfortress. As it was, Supermarine just did not have the workforce or factory capacity to push forward the project and when the prototype was destroyed on its jigs, during the Luftwaffe attack on the Woolston Supermarine factory in September 1940, the bomber project was cancelled.

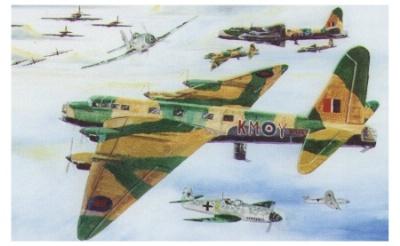

My painting of the Supermarine B12/36 as first designed by Mitchell (it was revised after his death) - attacked by Heinkel 113 fighters.

It was in 1936 that Mitchell was again diagnosed to have cancer. In February 1937 he went into hospital in London but returned to his home soon after. Mitchell had to give up work, however, he was often seen watching the testing of the Spitfire prototype at Eastleigh Airfield from his motor car when he should have been home resting. He flew to Vienna for treatment in late April 1937 but returned to England at the end of May. During the last months of his life, he liked to sit in his garden, admire the flowers and listen to the bird song. He died of cancer on the 11th of June 1937 at the age of forty-two. Responsibility for the development of the Spitfire fell to "Joe" Smith, who had served as Supermarine's chief draughtsman for many years.

Mitchell had one son; Gordon. It is perhaps surprising that for years no proper biography of Mitchell had ever been published (there are many books on the Spitfire's design and the Schneider races but they have little detail of Mitchell's early life). It fell to Doctor Gordon Mitchell to tell his father's story in the book "R.J. Mitchell - World Famous Aircraft Designer", later revised and reprinted as "R.J. Mitchell -Schooldays to Spitfire".

During the war, Leslie Howard, best remembered today for his role as Ashley in "Gone With The Wind", and one of the finest British film directors of the day, made a dramatised film of the story of the development of the Spitfire. It is more poignant for knowing that Howard himself was killed by the Nazis when an aeroplane carrying him home to England, over the Bay of Biscay, was singled out for interception by the Luftwaffe**. Called "The First Of The Few" and first shown in cinemas in 1942, the film is propaganda but of a gentle and particularly English kind. The opening sequence on an RAF station during the Battle of Britain looks a little awkward until you realise that these are not actors but actual serving pilots who fought in the Battle. The film traces the story of Mitchell and the Spitfire from Supermarine's Schneider win of 1922 up to Mitchell's death and beyond to the Battle of Britain. David Niven provides comic relief as a girl-chasing test pilot. Rosamund John plays Florence Mitchell. Howard himself plays Mitchell with a performance that none other than Noel Coward said was "acting that transcended acting".

In lieu of a proper biography of R.J. Mitchell, the film has been taken as a true record of Mitchell's life. However, there are some departures from the strict truth. Firstly the nature of Mitchell's illness is not touched upon, but this is more than understandable given the attitudes towards colostomy at the time. Somehow the myth grew that RJ Mitchell died from tuberculosis, even today this misconception is sometimes repeated on websites and magazine articles. Next, the film gives the impression that Mitchell worked himself to death and gave up his chance of recovery to finish the Spitfire in time for the coming war. This seems to be dramatic licence, it was not unusual for Mitchell to work late at the office but he also enjoyed a full family life and to have regularly taken part in sports like tennis, golf, snooker, shooting and sailing (he could often disappear for a couple of hours during the working day - sailing his boat from the factory slipway). Indeed the remarkable thing is that he led such a well-rounded life while suffering from serious illness and at the same time heading a design team producing the most advanced aircraft of the age. During his last years, it was the design of the Supermarine B12/36 bomber, the R1/36 fast-flying boat and the F37/35 four cannon fighter that preoccupied him, rather than the Spitfire. Lastly, an episode in the film where Mitchell and Niven's test-pilot character go to Germany in the early 1930s seems to be a complete invention. However, it is possible that Howard was incorporating events that occurred to Mutt Summers (Vickers/Supermarine test pilot and the pilot of the prototype Spitfire) or Beverly Shenstone (Vickers/Supermarine's aerodynamicist) both of whom visited or worked in Germany in this period (Mitchell's wife also had a skiing holiday in Austria in the mid '30s). In any event, the scene where Mitchell meets Messerschmitt in a German inn and comes away convinced he must design a fighter to protect Britain must be one of the most dramatic inventions in cinema history.

The film has other memorable moments, none less than the finale when David Niven`s test-pilot character, now in the Air Force and fresh from a dogfight with German Messerschmitt fighters, pushes back the cockpit canopy of his Spitfire and whispers to the sky,

"They can't take the Spitfires Mitch! ***

They can't take them!"

They can't take them!"

All who now live in peace and freedom would do well to remember that one man can make a difference and be thankful that Mitchell's Spitfire was ready in the summer of 1940.

Notes

* There is some doubt that it was wing-flutter that caused the loss of the S4. Pilot error, perhaps caused by ill-health or lack of practice has also been implicated (the S4 airframe was damaged by the collapse of its hanger before the race and repairs cut down on the practice flying that could be done). See the article "Dolittle Wins in Baltimore" by Michael Gough in the November 2005 Edition of "Airpower" magazine.

** Howard was killed on 1st June 1943 when Douglas DC3 G-AGBB "Flight 777" operated by KLM "in-exile" was shot down by a Ju88 when flying back to the UK from Lisbon, Portugal. Howard's manager, Alfred Chenhalls who was also on the flight, bore a resemblance to Winston Churchill and it seems likely that the aircraft was targeted because the Germans thought the Prime Minister was aboard. Certainly, after it was shot down the rumours of the "death of Churchill" spread throughout the German Forces in France. Incidentally, Howard and Chenhall's departure on their ultimate flight had been delayed by 3 days so that they could attend the Portuguese premiere of "The First of the Few". A full description of the events leading up to Howard's death can be read in an article by Richard Garrett in the book "Great Unsolved Mysteries", edited by John Canning, and published by Guild Publishing in 1984. Frank Falla, a Channel-Island newspaperman who was later imprisoned in France for publishing an underground newspaper, tells of being ordered by the German censor, Sonderfueher Kurt Goettmann, to prepare an article about the death of Churchill following the shooting down of Howard's aircraft. See "The Silent War" (Published by Leslie Frewin 1967, reprinted by Burbridge Ltd in the Channel Islands 1981)

*** RJ Mitchell was never known as "Reg" or "Reginald" except by his wife or parents. In true British, middle-class, between-wars fashion he would have been called "Mitchell" or "RJ" by his peers and "Mr Mitchell" by those who worked for him. The only exception to this were the pilots of the RAF high-speed flight who took part in the Schneider races, they alone called him "Mitch".

Suggested Further Reading

"Schneider Trophy To Spitfire - The Design Career Of R.J. Mitchell" by John Shelton - John Shelton examines Mitchell's 28 designs and recounts how each of his aircraft emerged in response to contemporary requirements and to prevailing design philosophies. ISBN-10: 0995678103 ISBN-13: 978-0995678101

"Beyond the Spitfire - The Unseen Designs of RJ Mitchell" by Ralph Pegram. This came out 8 years after John Shelton's book, it covers the unbuilt design projects rather than the ones that were actually built. As such, the two books compliment each other beautifully. It features some computer-generated colour images of some of the designs. First published by the History Press in 2016. ISBN 978 0 7509 6515 6.

"R. J. Mitchell: To the Spitfire" by John Shelton, published by Fonthill Media in 2022. ISBN-10: 178155885X. The best biography of Mitchell to date, the result of yet more ongoing research.

Sources:

"RJ Mitchell - World Famous Aircraft Designer" by Gordon Mitchell. ISBN 0 947750 053. Published in 1986 by Nelson and Saunders.

The same basic book was republished as "R.J. Mitchell, Schooldays to Spitfire" by Gordon Mitchell. ISBN 0 7524 23223. Published by Tempus Publishing Ltd in 2002 and by The History Press in 2006.

"Eagle to Spitfire - Pictorial Tribute to the Designs of RJ Mitchell" - An article by John Godwin in Air Enthusiast Issue 71 (Sept/Oct 1997).

"Spitfire Mitchell" - An article in "The Book of Flying" published by Evans Brothers Ltd 1948.

"Birth of a Legend - the Spitfire" by Jeffrey Quill. Published by Quiller Press, ISBN 0907621 64 3.

"Spitfire - A Test Pilot's Story" by Jeffrey Quill. Available from Crecy publishing in softback. ISBN 0-94755-472-6

"Spitfire -The Story of a Famous Fighter" by Bruce Robertson, first published by Harleyford Publications in 1960.