Dinger's Aviation Pages

The misconceptions and myths

of the British 1912 "ban" on monoplanes

Revised with new information, 14th Feb 2026.

Many books and articles, written from the mid 1940s into the 1990s, mistakenly imply that British authorities effectively banned or discouraged the use of monoplanes from before the start of WW1 through until the mid-1930s. That was certainly not the case. This article aims to shed light on the true story.

The Blackburn Type D monoplane of 1912. The oldest British aircraft still flying; it is part of the Shuttleworth Collection.

Britain got off to a slow start in heavier-than-air flight, the USA and France being the foremost pioneers in the field. In the USA, the biplane designs of the Wright brothers and Glen Curtiss predominated (although the American Henry W Walden was a pioneer of monoplane designs), while in France the biplane designs of Gabriel and Charles Voisin shared the skies with the monoplane designs of Léon Levavasseur and Louis Blériot. The early British aviation pioneers found inspiration from both sides of the Atlantic and both biplane and monoplane designs enjoyed popularity in the UK.

Most people think of monoplanes as being more modern and streamlined than biplanes. However, with the technologies and materials available in the early years of the twentieth century, it was impossible to build a true cantilever monoplane. The early monoplanes had to have their wings supported by cables attached to the fuselage.

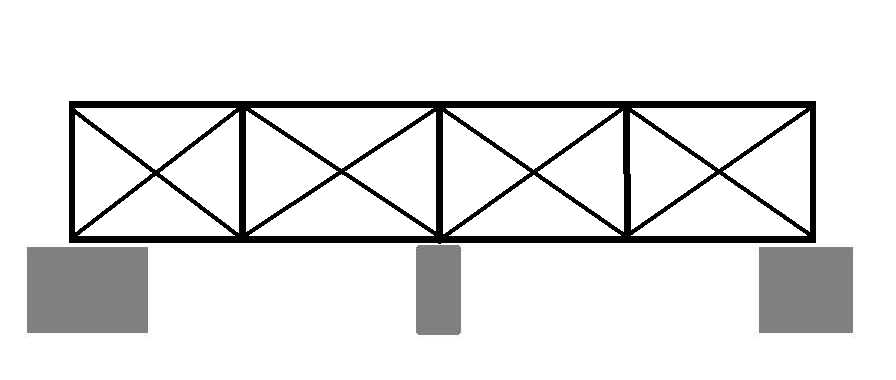

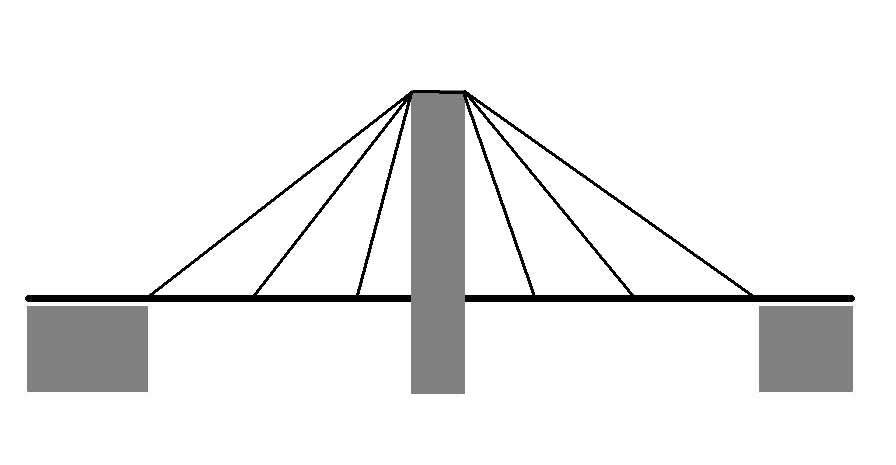

A simple analogy of the difference between a biplane and the early monoplanes is to consider the biplane as a girder bridge and the monoplane as a suspension bridge...

Most people think of monoplanes as being more modern and streamlined than biplanes. However, with the technologies and materials available in the early years of the twentieth century, it was impossible to build a true cantilever monoplane. The early monoplanes had to have their wings supported by cables attached to the fuselage.

A simple analogy of the difference between a biplane and the early monoplanes is to consider the biplane as a girder bridge and the monoplane as a suspension bridge...

A biplane can be considered to be like a girder bridge. If built with sufficient strength it can withstand both the downward force of gravity (or multiples of that if high "g" forces are encountered). Crucially, it can also withstand an upward force (remembering that in flight it is the wings that support the fuselage) and multiples of that if "negative-g" forces are encountered.

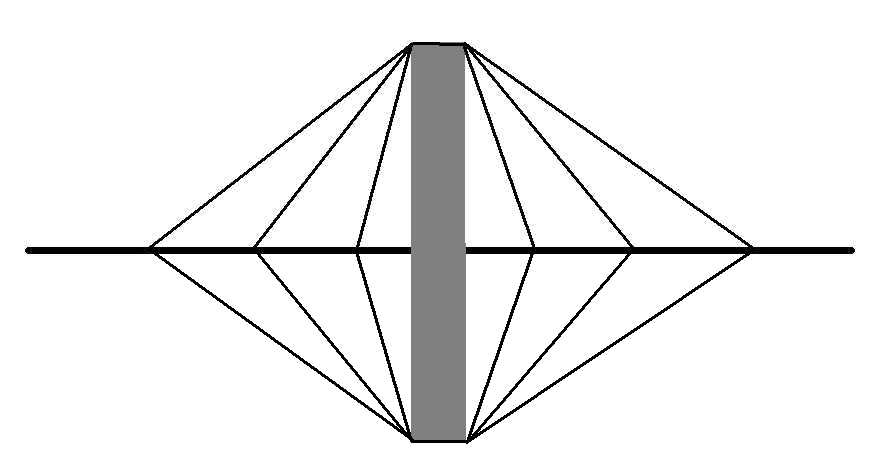

The early monoplanes can be compared to suspension bridges. With the materials and technologies available it was necessary to support them with wires or struts from either the top of the fuselage or a pylon on top of the fuselage. This provided the strength to withstand downward forces. However, in this analogy, there is nothing to provide support against upward forces. On an aircraft in flight, there are upward forces generated by the lift on the wings and in "negative-g" manoeuvres this is increased.

So, our analogy of a suspension bridge to a monoplane is not completely correct. We have to add another set of wires or struts underneath the wing.

Another view of the Blackburn Type D monoplane, shows the many bracing wires required to keep the wing in place (although some of the wires are associated with the wing warping system the aircraft used in lieu of ailerons). The Blackburn Type D first flew at the end of 1912, some five or six months after the trials to select the best type of aircraft to equip the new Royal Flying Corp. Its predecessor, the two-seat Type E "military" monoplane had been intended to take part in the trials but its steel framework had proved too heavy for the power of its engine.

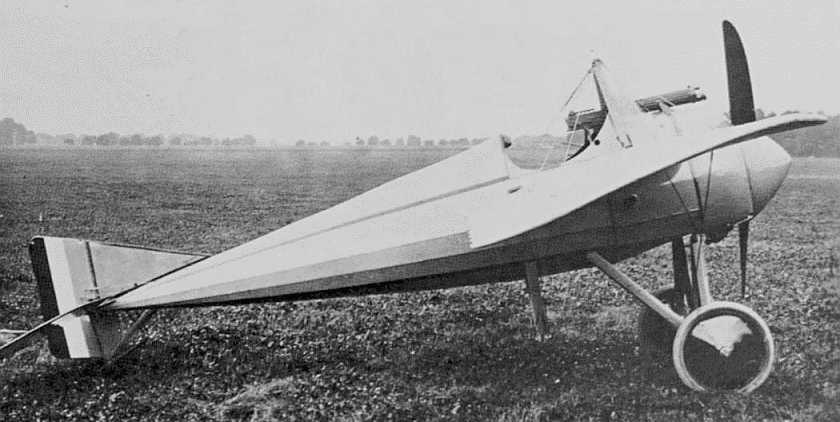

In August 1912, the British War office held a competition at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain to determine the best type of two-seat aircraft to be employed by the British Army. 19 monoplanes and 13 biplanes were submitted (not all were ready on the day of the competition). The winner of the "British built" category was the Cody V biplane, which was purchased by the war office and a second example was ordered. The Cody designs proved disapointing in service. Another of the competing biplanes, the Bristol GE2, was also purchased after the competition. Of the competing monoplanes, no less than five were purchased by the War Office, two Bristol Coanda monoplanes, two Deperdussin monoplanes (one built in France, the other in Britain) and a Bleriot XI-2 monoplane.

A Deperdussin monoplane.

The Royal Flying Corp (RFC) had been founded in April 1912, only 6 months before the competition; it had absorbed the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers and initially was also responsible for air operations for the Royal Navy (this was separated off to form the Royal Naval Air Service in July 1914). It had recently ordered some new Flanders monoplanes and Avro 500 biplanes but it also operated a miscellany of other types, many of them donated or purchased second-hand. It was the crash of one of these, a Nieuport monoplane on the 5th of July 1912, that caused the death of the first casualties of the RFC, Captain Eustace B Loraine and Staff-Sergeant Richard HV Wilson. The aircraft was executing a sharp turn when it crashed and it is presumed it stalled. This was a month before the competition to select new aircraft for the RFC.

Earlier, in February 1912, a series of crashes of monoplanes in France prompted the French Government to suspend all flying by monoplanes. The famous French aviation pioneer and manufacturer of monoplanes, Louis Blériot, looked into the crashes and in March he sent a report to the French government warning of a design flaw in his own earlier designs of monoplanes and those of other companies. The designs did not take into account increasing "g" loads on the wings. Blériot advised that the wire bracing of monoplanes be strengthened to take account of these forces. In the case of his own designs, this involved making the supporting cabane pylon on top of the fuselage higher to better handle the loads involved and doubling up some of the supporting wires. He advised that all new designs of aircraft should be tested with loads applied to the wings (usually sandbags) to make sure they did not give way. This should be done with both the aircraft in its normal position and also upside down. The French Government acted on Blériot's advice and quickly had all monoplanes in French service tested. Most were modified and put back into service,¹ although some proved to be unable to meet the new guidelines, and were scrapped. The issue seems to have been missed or ignored by the British aeronautical press, and no action was taken to rectify this defect in monoplanes in British service.

Louis Blériot; in 1909 he became the first man to fly the English Channel. His company manufactured a series of monoplane designs.

Only a few weeks after the completion of the competition to select aircraft for the RFC, the fatal crashes of two of the monoplanes selected by the trials forced the British Army to suspend the flying of all its monoplanes and order its pilots not to fly any civilian monoplanes. The first crash, on 6th September 1912, was of a Deperdussin monoplane; the pilot, Captain Patrick Hamilton and his observer, Lt Atholl Wyness-Stuart were both killed. The aircraft was seen to break up in the air. Ironically, Captain Hamilton owned his own private Deperdussin monoplane (he had spent much of the previous year flying it around the USA while on extended leave from the Army before shipping it back to the UK) and had gone to considerable expense to modify his own aircraft for greater strength, including doubling up some of the wing supporting wires. He may have been aware of some of the reports coming out of France, or maybe had just come to his own conclusions about the strength of the Derperdussin's wings after his extensive experience with the type. But the service machine he was flying had no such reinforcements to its structure. The second crash, on 10th September, was of a Bristol Coanda monoplane. Lt Edward Hotchkiss, the pilot and his observer, Lt Claude Bettington, were both killed. Their aircraft was seen to go into a steep dive and the fabric tore off one wing before the aircraft plummeted to the ground. It was the fact that both aircraft were seen to come apart in the air, with no possibility of pilot error or outside forces involved, that had forced the authorities to act.²

Captain Patrick Hamilton in his own two-seat Deperdussin monoplane which he had flown extensively in the USA and Mexico. He reportedly strengthened its structure and doubled up some of the bracing cables. However, the service Deperdussin he was killed in had no such improvements.

A Bristol Coanda monoplane. The designer, Henri Coandă, gave his name to the Coandă effect. Two were obtained by the RFC after the Larkhill trials and given the RFC serials 262 and 263. It was number 263 that crashed on the 10th of September 1912.

A committee was quickly set up to look into the accidents. It produced a report that was given to the government on the 3rd of December 1912 and made public the following February. It concluded that none of the accidents could be blamed on the aircraft being monoplanes. It did note that the very nature of biplane design "admits of ample strength" but it concluded that there was no reason why monoplanes should not be as safe as biplanes if properly designed. The committee listed a series of recommendations to apply to any future purchases of aircraft (clearly influenced by Blériots report to the French government) and advised that flying of monoplanes should recommence, providing that all existing monoplanes were inspected and found to either meet the recommendations or be modified to do so. It also recommended that the government should employ its own inspectors to advise on the safety of aircraft taken into future service and to regularly inspect RFC machines and engines. It also produced a list of subjects for the Government's Advisory Committee for Aeronautics to look into. One of the subjects listed was "Aerodynamic investigation of aeroplane wings designed to have sufficient strength without external bracing." Very prescient indeed!

Thus, the ban on monoplanes lasted only five months, and the RFC continued to operate monoplanes after the ban was lifted. The committee's recommendations were quickly adopted, and both biplanes and monoplanes in service with the RFC were tested to meet the new rules. In fact, the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough had been doing similar tests on its own products from as early as 1911. A department had been set up for this purpose, headed by Dr W.D. Douglas, with its first subject, in November 1911, being not a monoplane, but the Royal Aircraft Factory's own BE2 biplane, with it being suspended upside-down and the wings loaded to three times their normal loading. Testing showed that the BE2's wing stood up to the test without collapsing, but that the rear spar of the wings did deflect more than the front spar, which led to a redesign to stiffen the wing. Thus it was easy for the department to go on and test all the other aircraft types operated by the RFC. Some of the monoplanes on the strength of the RFC before the ban disappeared from service, presumably because they could not be strengthened or reconfigured to meet the new, more stringent, recommendations. It is noticeable that "Antoinette" style monoplanes, with supporting struts at the mid-points of the wings, such as the Flanders type, did not fly with the RFC again. However, the RFC would go on to order more monoplanes before the start of World War I. A formal organisation to test aircraft was put in place at the end of 1913, called at first the "Inspection Department of Military Aeronautical Material" it was soon renamed the "Aeronautical Inspection Department" (AID). By the end of World War I it had grown to have 10,000 staff.

The RFC had four "Flanders" monoplanes on strength before the ban on monoplanes flying. They were built on the principle of the French Antoinette monoplanes, with "king post" struts above and below the wings near their midpoints to act as anchors for supporting wires. This style of construction fell out of favour in both France and Britain after the ban, although the Austrians and Germans continued to use king posts on the wings of their Taube monoplanes until 1914. The Flanders monoplanes were broken up and their engines were used to power BE2 biplanes.

A Bristol Coanda monoplane being tested by loading its wing with sandbags, as recommended by Blériot. The Coanda monoplane had two elements that Blériot had identified as being an issue; a flat angle for the wires supporting the top of the wing and supporting wires on the bottom of the wing that relied on the undercarriage structure (meaning that damage to the undercarriage could lead to the collapse of the wing). Bristol redesigned the Coanda into the BR 7 biplane, which went on to be developed into the BR8 biplane; one of the many types ordered in small quantity by the Admiralty for the RNAS at the outbreak of war.

The British Army traditionally obtaining its weapons from government-run ordnance factories. So it had been a natural step to set up the Royal Aircraft Factory to design aircraft to specifications laid down by the forces, to be used by the fledgling RFC (the designs would be contracted-out to commercial firms to build in quantity). The result was the super-stable and safe-to-fly BE2 biplane, which conformed to exactly what had been asked for. The BE1, forerunner to the BE2, had taken part in the 1912 aircraft trials and demonstrated a clear superiority to all the other aircraft, but being government-built was ineligible for a prize or placing. The BE2 was adopted as the standard aircraft of the RFC and soon made up the bulk of its strength, along with some French designed Farman biplanes and Bleriot monoplanes. The only commercial independent British designed aircraft on the strength of the RFC were some Avro 500 biplanes.

The Blériot XI was used by armed forces across Europe. Louis Blériot set up a company to build them in Britain. The RFC and RNAS used two versions; a single-seat model with a 50 hp engine, and a two-seat version (the XI-2) with either a 70 or 80 hp engine. The single-seat verson was used for training while the two-seat verson was used for reconnaissance in France during the first months of WWI. This is one of a batch of XI-2 aircraft built in Britain with 80 hp Gnome engines in 1915.

Of course, the fledgling British aviation industry was concerned that its indigenous products were not being used by the RFC. In 1913 the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain asked the War Office to clearly state what type of aircraft it was prepared to order from British manufacturers. The War Office responded in February 1914 with a document outlining what tests an aircraft needed to pass to be accepted into service and the performance figures required to be met by the five distinct types of aircraft it required (a single-seat "light scout", two types of twin-seat reconnaissance aircraft and two types of twin-seat "fighting aeroplane"). No prejudice against monoplanes is evident in this document. British industry was quick to respond and by the start of World War One, Avro 504 and Sopwith Tabloid biplanes were in service with the RFC. At the same time the Royal Aircraft Factory was developing the FE series of pusher biplanes although there were delays getting them into service.

In 1913, eight new French Borel hydro-monoplanes were purchased for use by the Naval Wing of the RFC (The Royal Naval Air Service was separated off the following year). The Blériot company had established a factory in Britain and a number of its single and two-seat monoplanes were acquired by both the RFC and RNAS during 1913 and 1914. When war was declared in 1914, the RFC had a number of Blériot monoplanes in service and some of these were despatched to France, comprising two of the three Flights of No 3 Squadron. One took part in the first British reconnaissance flight of the war. Because of a shortage of British aircraft manufacturing capacity, the RFC scrambled to acquire more Blériot and Morane-Saulnier monoplanes from French sources early in the war, with some production of Morane-Saulnier Type "H" shoulder-wing monoplane aircraft taking place under contract in Britain (although these were then mostly only used as trainers). Just before war was declared, the RFC had tested a new single-seat Blériot "Parasol" monoplane and two examples were sent to France with No 3 Squadron. More Parasols were ordered from Blériot's British factory by both the RFC and RNAS.

Eight French Borel monoplane floatplanes (they were called "hydro-monoplanes") were ordered for use by the Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corp in 1913, the year after the ban was lifted. One flew with Winston Churchill as a passenger in October 1913. They were passed on to the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) when it was formed in July 1914. None survived in service by the end of December 1914. Many commentaries claim the RNAS was not affected by the monoplane ban, ignoring the fact that the RNAS was not in existence when the ban was in force! The Naval Wing's flying school at Eastchurch used biplanes made by the Short brothers, although a single, twin-seat Deperdussin monoplane did continue to be used at the school during the period of the ban. It seems that navy pilots were allowed to fly in civilian monoplanes during the period of the ban, unlike their army counterparts. At the time, it was common for officers who wanted a fast route to become pilots to pay for their own tuition at a civilian flying school.

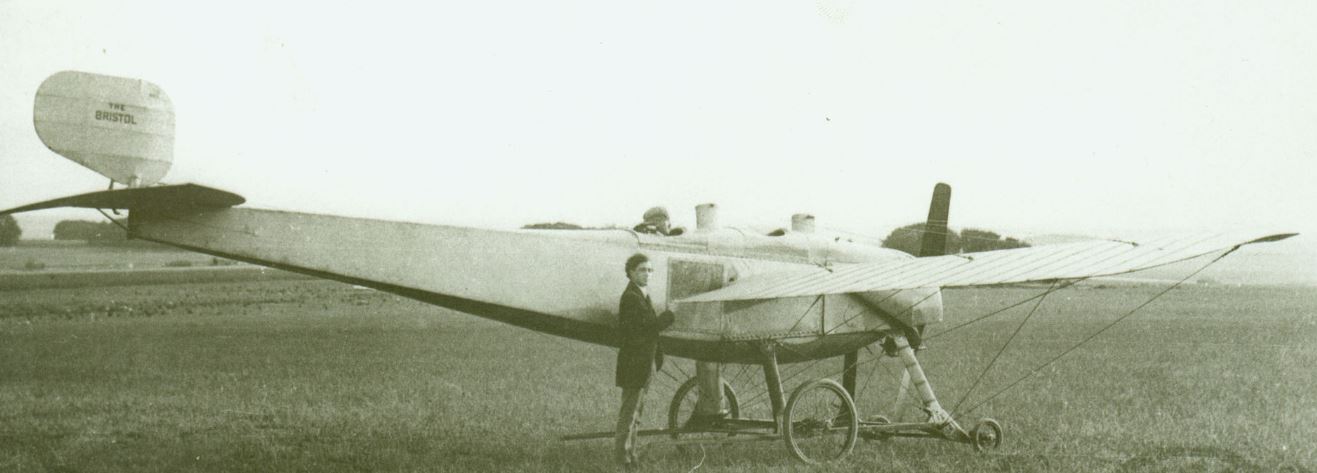

Used by the RNAS during WW1 was the sole example of the Dyott monoplane, built in early 1913 for George Dyott by Hewlett and Blondeau Ltd of Clapham, South London. Dyott had spent much of 1911 on a tour around the USA and Mexico with a pair of Deperdussin monoplanes in the company of Captain Patrick Hamilton, who was killed in one of the crashes that prompted the brief ban on monoplanes by the RFC. The Dyott Monoplane was designed with a view to it being used as a "courier" aircraft by the RFC but the 5 month ban on monoplanes stopped that aspiration. Instead, it was shipped over the Atlantic and spent the summer of 1913 being flown by Dyott on a tour around the United States. Shipped back to the UK, it was being prepared for a flight to India when war was declared and it was requisitioned by the Navy. It was briefly used for training and patrols over the English Channel based out of Dover. It was probably often flown in service by its original designer (George Dyott was commissioned in the RNAS and served as a Flight Commander at Dover).

Built in Britain at the famous Brooklands aerodrome, the single-seat Blériot Parasol monoplane was used in small numbers by both the RFC and RNAS for the first two years of WWI. Some had large cockpit windscreens that filled the gap between the fuselage and wing. The RFC mostly used the type for training (although two examples were some of the first aircraft sent to France with No 3 Squadron when war was declared), while the RNAS used them on anti-Zeppelin patrols over the Thames. This example, sporting an unusual camouflage colour scheme, was used by the RFC Number 9 Squadron for experimental wireless trials. The British Blériot company later opened up a large factory at Addlestone near Brooklands to produce SPAD S.VII biplane fighters and also build Avro 504s and SE5As under contract.

Used by the RNAS during WW1 was the sole example of the Dyott monoplane, built in early 1913 for George Dyott by Hewlett and Blondeau Ltd of Clapham, South London. Dyott had spent much of 1911 on a tour around the USA and Mexico with a pair of Deperdussin monoplanes in the company of Captain Patrick Hamilton, who was killed in one of the crashes that prompted the brief ban on monoplanes by the RFC. The Dyott Monoplane was designed with a view to it being used as a "courier" aircraft by the RFC but the 5 month ban on monoplanes stopped that aspiration. Instead, it was shipped over the Atlantic and spent the summer of 1913 being flown by Dyott on a tour around the United States. Shipped back to the UK, it was being prepared for a flight to India when war was declared and it was requisitioned by the Navy. It was briefly used for training and patrols over the English Channel based out of Dover. It was probably often flown in service by its original designer (George Dyott was commissioned in the RNAS and served as a Flight Commander at Dover).

Built in Britain at the famous Brooklands aerodrome, the single-seat Blériot Parasol monoplane was used in small numbers by both the RFC and RNAS for the first two years of WWI. Some had large cockpit windscreens that filled the gap between the fuselage and wing. The RFC mostly used the type for training (although two examples were some of the first aircraft sent to France with No 3 Squadron when war was declared), while the RNAS used them on anti-Zeppelin patrols over the Thames. This example, sporting an unusual camouflage colour scheme, was used by the RFC Number 9 Squadron for experimental wireless trials. The British Blériot company later opened up a large factory at Addlestone near Brooklands to produce SPAD S.VII biplane fighters and also build Avro 504s and SE5As under contract.

Two other monoplane types that saw service with the British in the first part of the war were the French REP Type "L" and the Morane-Saulnier Type "L". Both were of the parasol-wing layout. The REP L was used exclusively by the RNAS while the Morane-Saulnier L was used by both the RFC and RNAS. It was a Morane-Saulnier L of the RNAS that accounted for the first Zeppelin (the LZ 37) destroyed in the air.

Two parasol monoplanes operated by the British in the early war years, the Robert Esnault-Pelterie (REP) type "L" and the Morane-Saulnier Type "L". Note that both needed pylons to provide an anchor for the wires supporting the wings. Both were notoriously difficult to control and only the best pilots got the most out of them.

The Morane-Saulnier Type "H" shoulder-wing monoplane was produced in the UK by the Grahame-White company of Hendon (the current site of the RAF Museum). The Royal Flying Corp used them as training machines (although a single British example did serve in France). The Germans had more belligerent uses for the design, producing it as the Pfalz E.1 to E.VI fighters and forming the basis for the famous Fokker Eindecker series of fighters. In the photos of all these French-designed monoplanes notice the extra structure underneath the fuselage to ensure the bracing wires under the wings could continue to function if the undercarriage was damaged.

The Morane-Saulnier Type "H" shoulder-wing monoplane was produced in the UK by the Grahame-White company of Hendon (the current site of the RAF Museum). The Royal Flying Corp used them as training machines (although a single British example did serve in France). The Germans had more belligerent uses for the design, producing it as the Pfalz E.1 to E.VI fighters and forming the basis for the famous Fokker Eindecker series of fighters. In the photos of all these French-designed monoplanes notice the extra structure underneath the fuselage to ensure the bracing wires under the wings could continue to function if the undercarriage was damaged.

When the RNAS broke away in 1914, it largely adopted a different approach to procurement to that of the RFC, taking on a large range of aircraft from different commercial companies and then ordering further examples and developments of those designs that did best, "survival of the fittest" if you like. The Navy's approach did bring to the fore successful designs from Shorts, Fairey, Vickers and Sopwith but it also lead to tremendous wastage of resources, money, and sometimes lives in the first year of the war on a whole range of projects that never went into service or saw only limited production. Meanwhile, the Army's BE2 was found to be too ponderous to cope with the introduction of dedicated German fighter aircraft and the Royal Aircraft Factory was forced to close by a campaign run by Noel Pemberton Billing and CG Grey. This was a pity since the Factory had just produced the outstanding SE5 fighter and had some promising designs for both aircraft and engines in development. Bizarrely, the Admiralty Air Department had its own design staff who created a range of different aircraft during WWI (all biplanes), construction of which were contracted out to private companies. None of these designs was successful during the war, yet the Admiralty Air Department did not attract the criticism levelled at the Royal Aircraft Factory. It is particularly ironic that Pemberton Billing's company, Supermarine (which he sold when he entered Parliament), went on to have post-war success developing the Air Department's AD Flying Boat. So there were two quite distinct organisations selecting aircraft for British use during World War One, the Army and the Navy, they both increasingly chose to use biplanes rather than monoplanes (although the RFC persevered with the French parasol Morane-Saulnier designs in the front line until 1917).

The parasol monoplane single-seat Morane-Saulnier Type "L" was followed by the two-seat MS24 type "P" (seen above) designed specifically for the RFC which was a much better aircraft, seeing service until 1917. The improved view of the ground for reconnaissance and scouting was an obvious advantage for parasol monoplane designs. Hugh Trenchard, commander of the RFC in France, was an advocate for the continued use of parasol monoplanes.

The inherent strength of the biplane layout, coupled with the inbuilt redundancy in structure enabled a biplane to survive damage much better than a monoplane. The increased wing area of a biplane enabled lower landing speeds and increased rate of climb to clear obstacles, making operation from the small landing fields in France much safer. The advantage of drag reduction offered by a monoplane was negligible at the speeds attained in WWI and engine power was the most significant factor in speed performance. Thus the only real advantage of a monoplane built with the technology available during most of WWI was better visibility of the ground for parasol types and better visibility in the upper hemisphere for low and mid-wing designs. Thus the biplane came to predominate during WWI, not only with the British Army and Navy but also with the Germans, French, Americans, Italians, Austrians and Russians. There is, of course, one major exception to this, the "Fokker Scourge" of 1915 caused by the introduction of the Fokker Eindecker monoplane. However, the Eindecker's success was not due to its monoplane layout (it was a development from the French Morane-Saulnier H shoulder-wing monoplane) but the combination of its then-unique synchronised machine gun (allowing it to fire through the propeller arc) and the fitting of increasingly powerful engines. Perhaps more important than any technological advantage was the German's formation of units equipped with the Eindeker dedicated to shooting down enemy aircraft and the development of the tactics that went along with it. The Fokker was countered by biplane designs from both the French and British. Manoeuvrability became greatly prized during the dogfights that predominated during the war, and the increased wing area of biplanes enabled tighter turning circles.

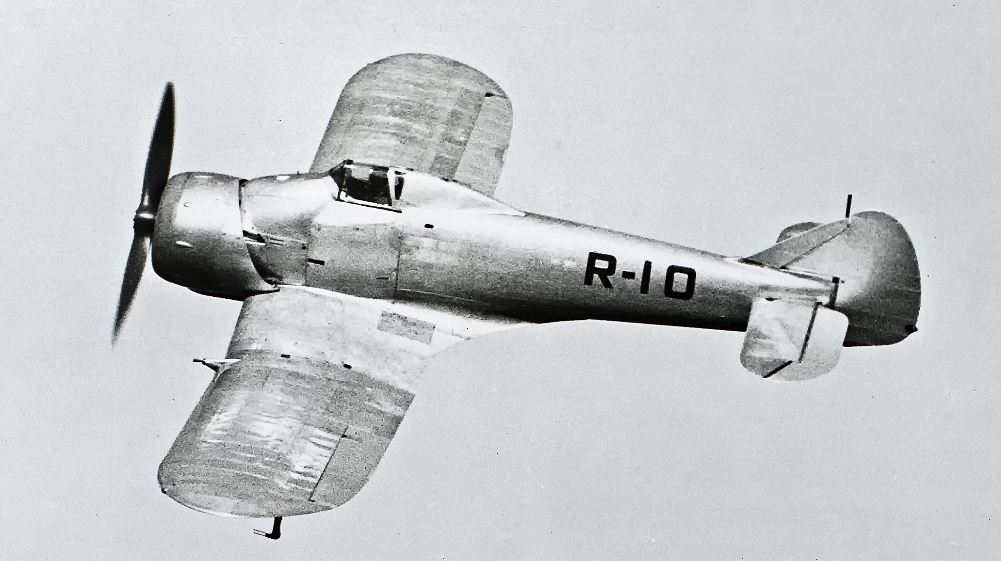

The RFC took delivery of 3 Morane-Saulner Type "N" monoplanes in 1915, powered by an 80 hp Le Rhone engine. It was a more streamlined and stronger version of the earlier Type "H". They were nicknamed "Bullets" by the RFC, a name that came to be applied to all the similar looking Type "I" and "V" and then the Bristol M.1C. The Type N showed a clear superiority over a captured Fokker Eindekker it was tested against, and the British were very enthusiastic about it, ordering another 24 examples and prompting the enquiry if a version with a more powerful 110 hp engine could be produced.

However, there is one thread of monoplane use by the British that is little-remembered. The RFC took delivery of a small number of French Morane-Saulnier Type N monoplanes. These were a streamlined and stronger version of the earlier Type H. They had a spinner on the front of their propellers that gave them a distinctive look, leading to the nickname "bullets". With a top speed of 89mph (144 kph), the RFC was very impressed with these aircraft, and Hugh Trenchard, commander of the RFC in France, requested that more should be purchased and that a version with a more powerful 110-horsepower engine should be desirable. This led the Morane-Saulnier company to hastily convert some "N" airframes for the British, with the more powerful engine to produce the interim Type "I" (top sped 104 mph, 168 kph), followed by the Type "V" which had slightly larger wings and elevators and a larger fuel tank to double the endurance to 3 hours but with a slight drop in maximum speed to 102 mph (165 kph). Trenchard took a close interest in the development and trials of the Morane-Saulnier monoplanes, asking for weekly reports. Issued to Number 60 Squadron in France, the Type I and V were not liked by their pilots. Their high wing loading meant that their manoeuvrability was very poor, especially at altitude. "It had the gliding angle of a brick" commented one pilot, meaning it was difficult to land. If anything can be said to have soured the British view of monoplanes, it was their experience of the Morane-Saulnier Type I and V. One pilot wrote: " We were scared stiff of them, although they were the fastest thing in the sky at the time. Our main preoccupation, once having got into the air. was how to get down safely...". It is telling that the French themselves never operated the types. The French did take delivery of 30 examples of the improved Morane-Saulnier Type "AC", and two were given to the British to evaluate. The Type AC did away with bracing wires, replacing them with extended struts under the wings. It had a top speed of 111mph (178 kph). The French rated their performance as good, but not as good as their latest biplane fighter, the Spad S.VII, so production was cut short.

The French Morane-Saulnier Type "I" was developed from the earlier Type "N" specifically for the British Royal Flying Corps on the orders of Hugh Trenchard. Only 4 of the interim Type Is were delivered to the RFC before it was replaced by the Type "V" with the larger fuel capacity desired by the RFC for escort missions (30 examples of the Type V were delivered to the RFC). Both the Type I and V were used by the RFC during 1916 (the types were never used by the French themselves) before being passed on to the Russians. Issued to No 60 Squadron of the RFC, the Type V was not liked by British pilots because of control issues, a lack of manoeuvrability and the high landing speed. Morane-Saulnier would go on to further refine the design to produce the Type "AC", two examples of which were received by the RFC for evaluation. The French took delivery of 30 examples of the Type AC but deemed it inferior to the Spad SVII, so they did not order any more.

What is striking is that while the RFC and RNAS continued to acquire French monoplanes and French monoplane designs built under licence in Britain, British manufacturers stopped putting forward any new monoplane designs. That was until the Bristol M.1, which first flew in July 1916. Most histories present the Bristol M.1 as a maverick private venture by the Bristol Aircraft company, a design seemingly well ahead of its time just by virtue of being a monoplane. This ignores the fact that it was identical in general layout to the French Morane-Saulnier monoplane designs already used by the RFC, down to having the identical front spinner to give it the same "Bullet" designation. With the RFC requesting a version of the Morane-Saulnier "N" monoplane with the more powerful 110 horsepower Le Rhône engine its easy to see why Bristol would have jumped at the chance to produce their own monoplane with the same power of engine, knowing it would be looked at favourably. The prototype Bristol M.1 flew the month after the first Morane-Saulnier Type V was delivered to the RFC. In its initial prototype form, it was reported to have an excellent top speed of 128mph, but that was without any armament or service equipment. Four examples with guns fitted were ordered for evaluation (designated M.1B) but the increase in weight meant that the top speed had dropped to 112 mph, comparable with biplane fighters like the Sopwith Pup and Nieuport 17. The first M.1B was sent to France for evaluation. It was rejected, principally because of its poor downward visibility, since the RFC still saw the role of single-seat aircraft as primarily that of reconnaissance (that's why the RFC called them "scouts" rather than "fighters"). It had only half the 3 hour endurence that had been demanded for the Morane-Saulnier type V to enable it to escort two-seat bombers and recce aircraft. It was judged to not have the manoeuvrability to survive in the tight-turning dogfights over the Western Front. Its landing speed was considered too high for operations from the small airfields in France. However, even with all these caveats, the Bristol M.1 was still ordered into production in its M.1C form, 32 of the production run of 125 (along with all three of the earlier M.1Bs) were used in the Middle East and the Balkans for the last 18 months of the war. Their low endurance limited their use, and they showed no advantage over the German and Austrian aircraft they encountered. The story that one pilot achieved "Ace" status flying the M.1C seems to be mistaken, combining the "kills" of two different pilots with similar sounding names. The M.1Cs were replaced by SE5as and Sopwith Camels in the front line in the Balkans before the end of the war. The remaining 93 M.1Cs were used for training pilots in the UK, usually without armament.

Bristol M.1C monoplane; this replica example flies at the Shuttleworth Collection. The fact that the British put the Bristol M.1C into production shows there was no bar to using monoplanes. It was less manoeuvrable than contemporary biplane fighters and slower than an SE5a fighter. It only had one machine gun, whereas twin guns became the standard later in the war. It had poor downward visibility, only slightly alleviated by having window sections cut out of the wing roots. The true top-speed performance figures for the M.1C are hard to determine, they may have been inflated by the speeds recorded by the prototype without any armament and post-war examples converted into racers.

Just as the mid-wing monoplane was falling out of favour with both the British, French and Germans, the appearance, in early 1917, of the superlative Sopwith Triplane with the British RNAS forced a reappraisal of aircraft design. This prompted a myriad of triplane designs from German and Austrian aircraft manufacturers, the most famous being the Fokker Dr1, again stressing the importance of manoeuvrability. Quadraplane projects even had a period of popularity amongst British designers (the Armstrong Whitworth FK10, Supermarine Nighthawk and Wright Quadraplane) although none ended up seeing combat service. It may seem strange to us now, but from 1917 into the early 1920s, to the public it was monoplanes that were seen as "old-fashioned". If an illustrator wanted to show an out-of-date aircraft it would usually be a monoplane.

"Old fashioned" monoplanes. A cartoon by Thomas Maybank, circa 1920.

But the British did not give up on monoplanes. The next British monoplane considered for use during WW1 was the Sopwith Swallow, a parasol monoplane version of the famous Sopwith Camel. The impetus for its development came from the Air Board (forerunner of the Air Ministry) which sponsored the design. Again giving the lie to the belief that the authorities were prejudiced against monoplanes.

In 1918, Harry Hawker had a Sopwith Camel stripped of its armament and converted into a parasol monoplane with slightly swept-back wings for use as his personal runabout. Called the "Scooter", its wings were supported by wires from a high pylon above the fuselage. Intrigued by the possibilities of a monoplane Camel, the Air Board (forerunner of the Air Ministry) placed an order for a prototype of a developed version with two machine guns. Called the Swallow, it still had to have a pylon to anchor supporting wires above the wing (not evident in this photo). Considered for use as a shipboard fighter, testing showed it had inferior performance to the biplane Camel with the same engine.

Like the British, the Germans had largely gone over to using biplanes. However, late in the war the Germans produced the parasol monoplane Fokker D.VIII but its introduction into service was marred by failures caused by poor workmanship in construction. However it was notable for having a wing that was strong enough to not require a pylon and supporting wires above it. A few metal Junkers CL1 ground-attack monoplanes were in service at the war's end as well as some Hansa-Brandenburg W-29 monoplane floatplanes. The Junkers D1 metal monoplane was on the verge of entering service, although in its initial form it was not as fast as the latest contemporary allied biplane fighters and was certainly not as manoeuvrable; although later projected developments (including two-seaters) may have been truly formidable.

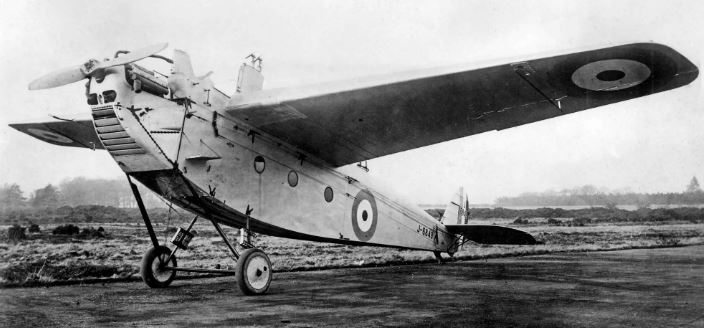

The formation of the Royal Air Force and the establishment of the Air Ministry meant there was now a single organisation to oversee British military aircraft procurement. When the war was over there was a period of retrenchment in defence spending. However, a surprising number of new aircraft were ordered by the Air Ministry in the 1920s. The Ministry was not averse to considering monoplane designs, on the contrary, it financed the building of such experimental monoplanes as the Handley Page HP20, de Havilland DH29, Westland Dreadnaught, Westland Pterodactyl and Beardmore Inflexible, and paid for numerous monoplanes from British companies for its official specifications. However, there were overriding reasons why biplanes still predominated. The lower landing speed of biplanes led to fewer fatal accidents. The small size of the RAF's legacy airfields also militated against the longer take-off and landing runs of monoplanes. With hindsight, we can see that airfields were bound to get bigger, but that was not a given in the 1920s and early 1930s. The pace of aviation advance just from 1903 made many assume that further advances were bound to find solutions to the safety and airfield issues. The Air Ministry did not want to commit to an expensive programme to extend the size of its airfields if some new technical advance provided a solution. Indeed, the adoption of flaps and Handley Page slats seemed to hold out the promise of just such an advance. Experiments with catapult launches and arrestor landings of bombers seemed to offer another alternative to building long runways.³

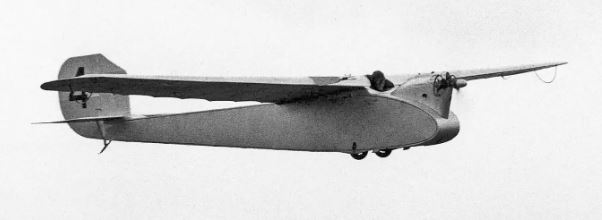

The Handley Page HP20 experimental monoplane of 1921. Essentially a wartime DH9A bomber fitted with a thick monoplane wing, it featured leading-edge slats to bring down the landing speed. The strong wing structure did not need supporting wires to a pylon above the wing, however that extra strength was only gained at the expense of the wing being much heavier, the HP20 weighed some 1,800 Ib (816 kg) more than a biplane DH9A. The HP20's development was paid for by the Air Ministry.

Another disadvantage of the early monoplanes was the weight of their wings. It may seem counter-intuitive that a single wing could weigh more than two, but that was usually the case with monoplanes built in the 1920s. They needed strong, thick spars to support the cantilever structure and extensive internal bracing to provide rigidity. Whereas biplane wings could be built with less weight, the strength and rigidity being proved by the wire and strut bracing between them. This extra weight had an effect on the speed and climb performance of monoplane fighters and meant monoplane bombers and transports could not lift the payload of equivalent biplane designs.

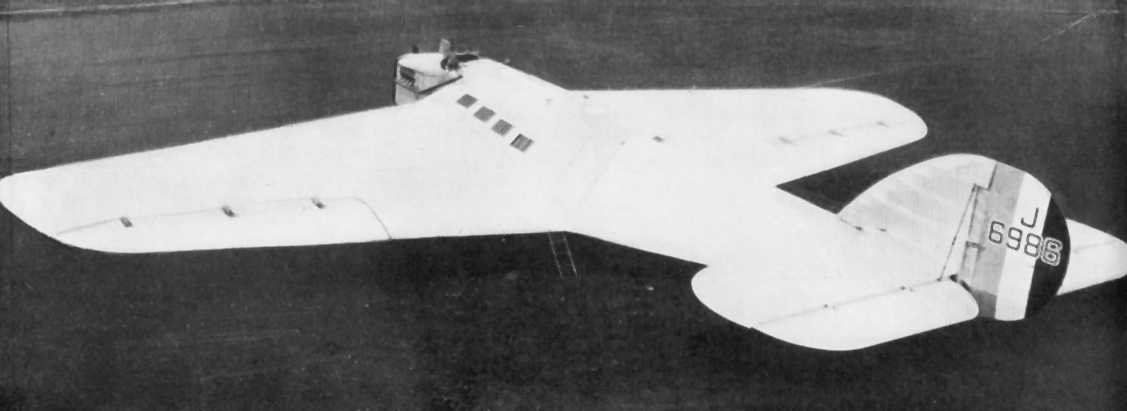

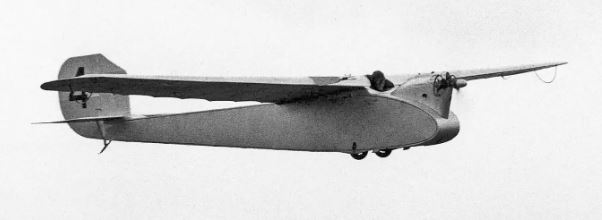

The de Havilland DH29 Doncaster of 1921 lays claim to be the first British-designed, cantilever-winged (without bracing wires or struts) monoplane. The Air Ministry paid for its development. What looks like a pylon on top of the fuselage is a small header gravity feed tank for the fuel supply. The monoplane wings were made of wood with a fabric covering.

A rear view of a Doncaster, this was before the fitting of the gravity feed-tank.The projection you can see above the fuselage is a stack to carry the engine exhaust clear of the pilot. Two Doncasters were built and one was purchased outright by the Air Ministry and fitted out as a bomber with a dorsal gun position. The other DH 29 was intended for commercial use but it ended up with the Air Ministry as well. There were control issues with the design and de Havilland found it easier to develop a biplane version, the DH34, which proved a commercial success.

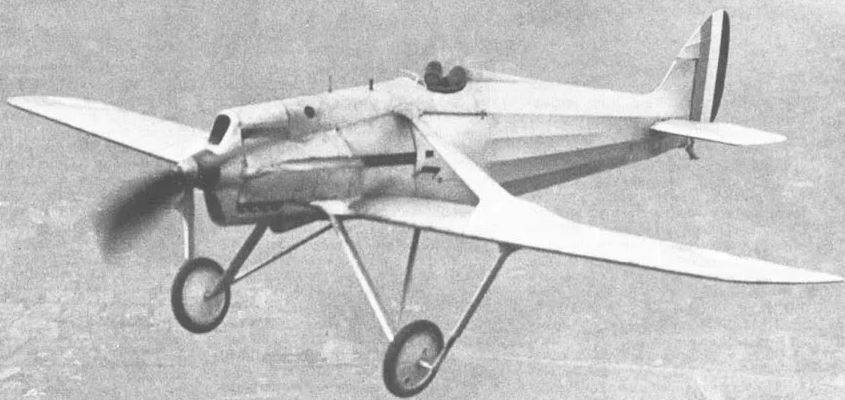

In 1921, the Air Ministry issued specification 2/21 to finance a novel idea from the Bristol Aircraft Company. Their modular Bullfinch aircraft could be put together in two ways: as a single-seat parasol monoplane fighter (pictured above) or as a two-seat biplane bomber, with the second, purely cantilever wing mounted under the rear fuselage. Notice that the upper wing did not require a pylon with supporting wires above it. Three prototypes were built, two in single-seat fighter configuration and one as a two-seat biplane. Testing showed the single-seat monoplane was considerably slower than the RAF's current biplane fighter, the Gloster Grebe, even though the Grebe had a less powerful engine. The two-seat version of the Bullfinch was also disappointing, not being able to carry the required weight of equipment and bombs.

The Air Ministry paid for the construction of two prototype Blackburn R.2 Airedale parasol monoplanes for specification 37/22 for a three-seat carrier reconnaissance aircraft. Another parasol monoplane that did not need supporting wires above the wing. First flying in 1925, the Airedale showed no advantage over the types already in service. A.J Jackson's Putnam book on Blackburn aircraft claimed the Airedale was rejected because of Air Ministry aversion to monoplanes, while offering no evidence for this and failing to explain why the Air Ministry would pay for the building of two prototypes (under contract no 479024/24) in the first place.

Another advanced monoplane concept the Air Ministry wanted to explore was the "Dreadnaught", the desigh of Russian émigré Nicolas Woyevodaky. In 1922, the Ministry put out specification 6/21 to ask for tenders to build this large, blended-wing monoplane. The Westland Aircraft Company was selected for the task (an injection of cash that kept the company in business), with the aircraft ready to fly in May 1924. Unfortunately it crashed on its maiden flight, seriously injuring the pilot.

In 1923 the Air Ministry contracted the English Electric company to build a lightweight monoplane single-seat trainer designed by William Oke Manning. Meant to provide a cheap way to give pilots in the RAF reserve continued flying experience, specification 4/23 was written around the design, which first flew in April 1923 and was called the "Wren". The Air Ministry paid for the full development of the aircraft and purchased the prototype which went through extensive tests at Martlesham Heath. English Electric went on to build another two examples of the Wren, one of which is still in existence in the Shuttleworth Collection and still regularly flies.

The Parnell Pixie (J7323) was one of a number of small, single-seat monoplanes purchased by the Air Ministry for evaluation in 1924/25. Other examples were the ANEC I (Air Ministry registration J7506) and AVRO 560 (J7322).

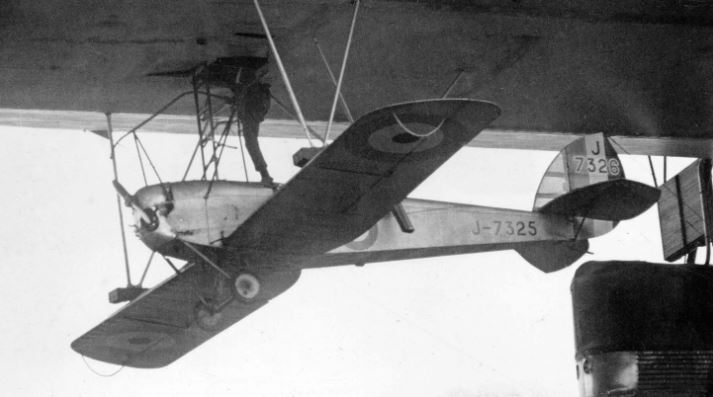

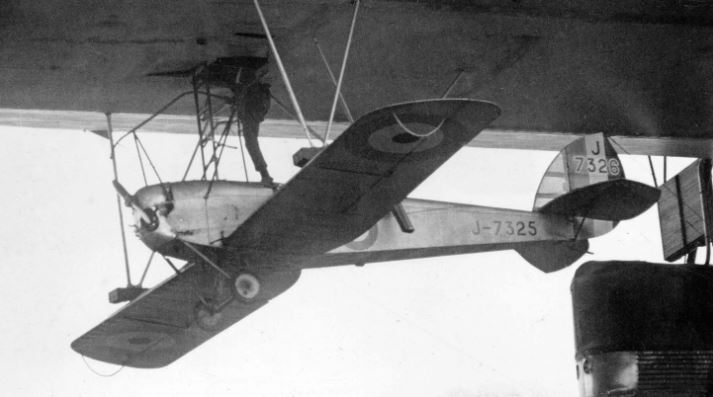

In 1923 the Air Ministry contracted for eight examples of the de Havilland DH53 Hummingbird monoplane (Air Ministry specification 44/23). These were delivered the following year. One (J7325) was used for trials for launching and recovery from the airship R-33. Note that the aircraft has been repaired with the rudder from another Hummingbird (J7326).

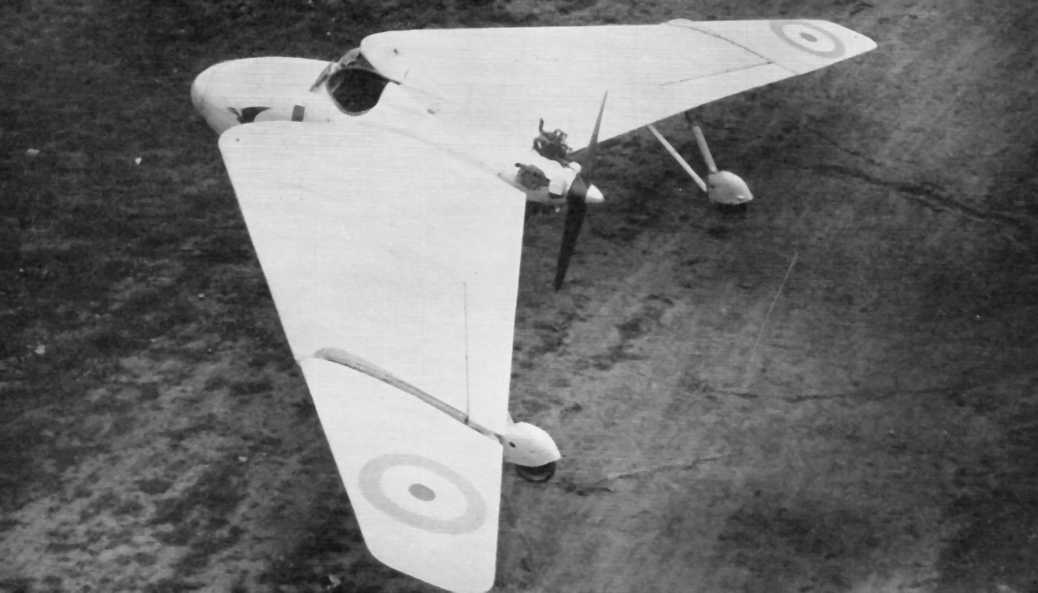

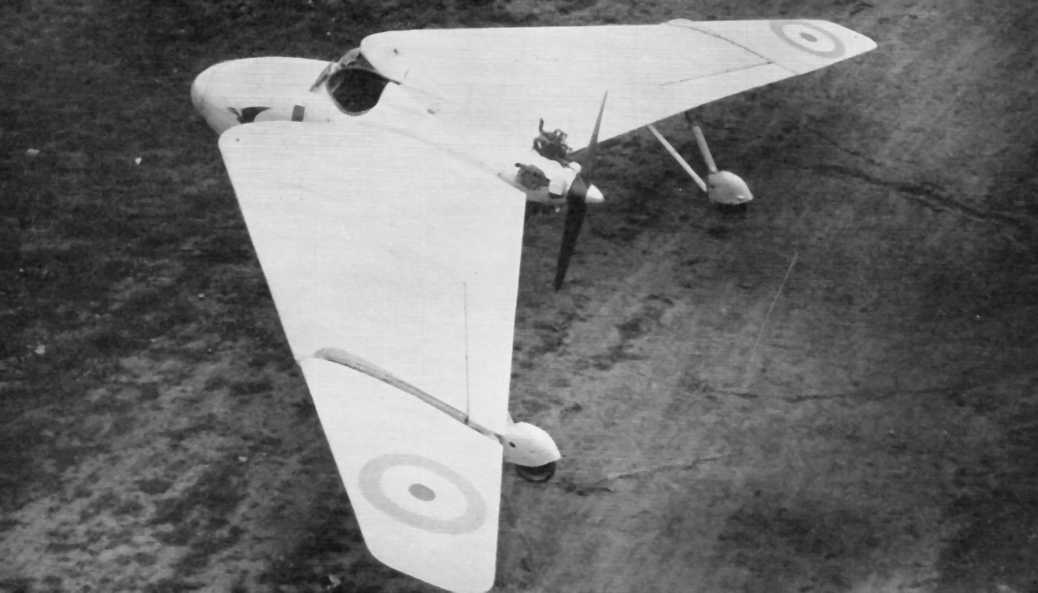

In 1926, Captain Geoffrey Hill approached the Air Ministry with his ideas on tailess monoplane. The Air Ministry got the Westland Aircraft company to employ Hill and sponsored his initial design ideas, leading to them issuing Specification 23/26 and paying for the building of the prototype Pterodactyl IA (seen above, first flight in June 1928). This led on to follow up Specification 16/29 for the Pterodactyl Mark IV three-seat cabin monoplane (first flight in March 1931), and F.3/32 for the Mk V twin-seat fighter (first flight May 1934). At every stage sponsored and paid for by the Air Ministry.

It is often forgotten that the Air Ministry sponsored and paid for the Supermarine, Gloster and Short monoplane contenders for the 1925 and 1927 Schneider Trophy races. Above is the Supermarine S4, built to an Air Ministry specification issued in 1923, it was entered in the 1925 race. It was a true cantilever design, having no bracing wires or struts to the wing. Unfortunately, it crashed during a test run. The subsequent Supermarine S5 and S6 designs reverted to having bracing wires.

The Gloster VI, designed by Henry Folland, was another monoplane entry for the Schneider Trophy paid for by the Air Ministry. Two examples were built for the 1929 competition, but engine trouble stopped them from competing in the actual race. The day after the race, one of the Gloster VIs raised the World Speed record to 336.3 mph (541 kph), only for it to be snatched back a few hours later by the Supermarine S6. One of the Glosters remained with the RAF High Speed Flight and was used for practice for the 1931 Schneider Trophy race.

Another monoplane Schneider Trophy design sponsored and paid for by the Air Ministry, the Short Crusader. It was intended for the 1927 competition but it was evident that it would be too slow to win and so was used as a practice aircraft instead. It crashed prior to the competition.

In 1921, the Air Ministry issued specification 2/21 to finance a novel idea from the Bristol Aircraft Company. Their modular Bullfinch aircraft could be put together in two ways: as a single-seat parasol monoplane fighter (pictured above) or as a two-seat biplane bomber, with the second, purely cantilever wing mounted under the rear fuselage. Notice that the upper wing did not require a pylon with supporting wires above it. Three prototypes were built, two in single-seat fighter configuration and one as a two-seat biplane. Testing showed the single-seat monoplane was considerably slower than the RAF's current biplane fighter, the Gloster Grebe, even though the Grebe had a less powerful engine. The two-seat version of the Bullfinch was also disappointing, not being able to carry the required weight of equipment and bombs.

The Air Ministry paid for the construction of two prototype Blackburn R.2 Airedale parasol monoplanes for specification 37/22 for a three-seat carrier reconnaissance aircraft. Another parasol monoplane that did not need supporting wires above the wing. First flying in 1925, the Airedale showed no advantage over the types already in service. A.J Jackson's Putnam book on Blackburn aircraft claimed the Airedale was rejected because of Air Ministry aversion to monoplanes, while offering no evidence for this and failing to explain why the Air Ministry would pay for the building of two prototypes (under contract no 479024/24) in the first place.

Another advanced monoplane concept the Air Ministry wanted to explore was the "Dreadnaught", the desigh of Russian émigré Nicolas Woyevodaky. In 1922, the Ministry put out specification 6/21 to ask for tenders to build this large, blended-wing monoplane. The Westland Aircraft Company was selected for the task (an injection of cash that kept the company in business), with the aircraft ready to fly in May 1924. Unfortunately it crashed on its maiden flight, seriously injuring the pilot.

In 1923 the Air Ministry contracted the English Electric company to build a lightweight monoplane single-seat trainer designed by William Oke Manning. Meant to provide a cheap way to give pilots in the RAF reserve continued flying experience, specification 4/23 was written around the design, which first flew in April 1923 and was called the "Wren". The Air Ministry paid for the full development of the aircraft and purchased the prototype which went through extensive tests at Martlesham Heath. English Electric went on to build another two examples of the Wren, one of which is still in existence in the Shuttleworth Collection and still regularly flies.

The Parnell Pixie (J7323) was one of a number of small, single-seat monoplanes purchased by the Air Ministry for evaluation in 1924/25. Other examples were the ANEC I (Air Ministry registration J7506) and AVRO 560 (J7322).

In 1923 the Air Ministry contracted for eight examples of the de Havilland DH53 Hummingbird monoplane (Air Ministry specification 44/23). These were delivered the following year. One (J7325) was used for trials for launching and recovery from the airship R-33. Note that the aircraft has been repaired with the rudder from another Hummingbird (J7326).

In 1926, Captain Geoffrey Hill approached the Air Ministry with his ideas on tailess monoplane. The Air Ministry got the Westland Aircraft company to employ Hill and sponsored his initial design ideas, leading to them issuing Specification 23/26 and paying for the building of the prototype Pterodactyl IA (seen above, first flight in June 1928). This led on to follow up Specification 16/29 for the Pterodactyl Mark IV three-seat cabin monoplane (first flight in March 1931), and F.3/32 for the Mk V twin-seat fighter (first flight May 1934). At every stage sponsored and paid for by the Air Ministry.

It is often forgotten that the Air Ministry sponsored and paid for the Supermarine, Gloster and Short monoplane contenders for the 1925 and 1927 Schneider Trophy races. Above is the Supermarine S4, built to an Air Ministry specification issued in 1923, it was entered in the 1925 race. It was a true cantilever design, having no bracing wires or struts to the wing. Unfortunately, it crashed during a test run. The subsequent Supermarine S5 and S6 designs reverted to having bracing wires.

The Gloster VI, designed by Henry Folland, was another monoplane entry for the Schneider Trophy paid for by the Air Ministry. Two examples were built for the 1929 competition, but engine trouble stopped them from competing in the actual race. The day after the race, one of the Gloster VIs raised the World Speed record to 336.3 mph (541 kph), only for it to be snatched back a few hours later by the Supermarine S6. One of the Glosters remained with the RAF High Speed Flight and was used for practice for the 1931 Schneider Trophy race.

Another monoplane Schneider Trophy design sponsored and paid for by the Air Ministry, the Short Crusader. It was intended for the 1927 competition but it was evident that it would be too slow to win and so was used as a practice aircraft instead. It crashed prior to the competition.

Another reason for biplanes winning production orders was that with the engine power then available, the extra wing area of biplane fighters gave them an increased rate of climb and a higher ceiling than their monoplane contemporaries. There was no point striving for all-out top speed if the resulting aircraft could not climb fast enough to intercept opposing bombers coming over at height. When the Air ministry issued specification F20/27 for a fast-climbing "interceptor", none of the monoplanes put forward by the British aircraft industry could reach the climb performance required.

This is the de Havilland DH77 semi-cantilever monoplane fighter, one of four types of monoplane paid for by the Air Ministry for the F20/27 specification for a fast-climbing interceptor. The other monoplanes ordered were the Westland F20/27 low-wing braced monoplane, the Westland "Wizard" high-wing parasol monoplane and the Vickers Type 151 Jockey (see below). However, none of the monoplane entries for the specification could meet the climb requirements. The Hawker Fury biplane was ordered instead.

The Vickers Type 151 Jockey was structurally the most advanced monoplane fighter paid for by the Air Ministry for specification F20/27. It did not need bracing wires for the wing, using methods perfected by French engineer Michel Wibault. The Jockey prototype was lost after entering a flat spin. This prompted the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) to instigate a programme of research into flat spins. The results of this research were given to British commercial aircraft companies and heavily influenced the design of British monoplanes in the mid-to-late 1930s and into the war years. All paid for by the government.

The sleek-looking Westland "Wizard" parasol monoplane. In 1944, a note in the introduction to "The Book of Westland Aircraft", a book sponsored by the Westland company, blamed the rejection of the Wizard on prejudice against monoplanes within the Air Ministry (without offering any evidence). That same accusation has followed the description of the Westland Wizard ever since, repeated in Putnam's title "Westland Aircraft since 1915" by Derek N James, David Mondey's book "Westland", Taylor & Allward's book "Westland 50" (another book sponsored by the Westland company) and on to online articles on the Wizard on Wikipedia and Aviastar. In fact, it was the Air Ministry that picked up on the original Wizard racer's potential and paid for it to be modified into a fighter (Air Ministry contract number 841676/28). Submitted for specification F20/27 for an interceptor, it was comprehensively beaten in performance by the biplane Hawker Fury.

The other Westland monoplane entry for F20/27 to be paid for by the Air Ministry (contract no. 813869/27) was this streamlined looking design. First impressions can be deceptive, it suffered from interference drag at the wing roots, the cause of problems for many early monoplane designs. A closer inspection shows bracing wires above and below the wing. Performance was mediocre, not being able to meet the requirements for speed or rate of climb.

On the left is the anachronistic-looking Vickers biplane COW fighter, on the right is the Westland monoplane COW fighter, a larger derivative of the Westland F20/27 monoplane, both submitted for F29/27 the other 1927 specification calling for an interceptor. This was to mount a large calibre Coventry Ordnance Works (COW) gun. While it looks more modern, the Westland monoplane has bracing wires above and underneath the wings and it had a lacklustre performance. The biplane Vickers design had a much higher rate of climb to better meet the interceptor requirements.

One particular issue that plagued the early cantilever monoplanes was "aileron reversal". If the monoplane wing could not be made rigid enough, then the application of the ailerons at speed would cause the wing to bend in the opposite direction. This meant the aircraft banked in the opposite direction to that intended! Very disconcerting for the test pilot! Aileron reversal issues on even the tiny, stubby wings of the Bristol Type 72 "Racer" monoplane of 1922 caused its abandonment. The same issue scuppered the Bristol Type 95 Bagshot monoplane that first flew in 1927. Aileron reversal issues also plagued the Boulton Paul P31 Bittern twin-engined monoplane fighter; although the problem on the Bittern was eventually fixed, the delays incurred by doing so rendered the design obsolete.⁴

One of the few advanced British inter-war monoplane designs that were not financed by the Air Ministry was the Bristol Type 72 "Racer". It was built to demonstrate the superiority of the new Bristol Jupiter radial engine. Even though its stubby wings were braced by wires it still suffered from aileron reversal. It was judged to be very dangerous to handle and was scrapped after only seven flights.

Another Bristol monoplane, this one fully financed by the Air Ministry, was the Type 95 Bagshot (first flight July 1927). It was designed as a bomber-destroyer, able to carry two large calibre Coventry Ordnance Works (COW) guns. It suffered from alarming twisting of the wings, causing aileron reversal. The Air Ministry paid for the development of a stronger wing. When the Bagshot was cancelled the wing design was transferred to a three-engined bomber/transport project. When that in turn was cancelled, the multi-spar wing design was used on the Bristol Bombay bomber/transport project; skinned with Alclad, the wing became the first British stressed-skin monoplane to be designed. Financed at every stage by the Air Ministry.

Yet another monoplane bomber-destroyer financed by the Air Ministry; The Boulton Paul P31 Bittern, which first flew in 1927, was designed to have machine guns in the nose, mounted on a drum so they could be rotated to point upwards to attack enemy bombers from below. This photo shows it in its early configuration, in which it suffered from aileron reversal. The issue was eventually solved by adding extensive bracing struts to the underside of the wing. Because of its prolonged development period, its performance fell behind that of contemporary bombers and it was cancelled in 1933.

There seems to have grown up a perception that the British Air Ministry of the 1920s and 30s was composed of crusty old conservative Air Marshals who were somehow out of touch with modern trends. Nothing could be further from the truth. We are talking about a generation who had grown up surrounded by meteoric technological change, from horse transport to cars in a few short years, the introduction of the telephone and radio, the development of the aeroplane from a playboy's toy to a deadly weapon of war. This generation expected change in a way that even we in the 21st century do not. Many of their reasons for being cautious were not out of some hidebound outlook, on the contrary, it was a fear of investing too heavily in some new fad only to find it overtaken by some better innovation.

One of the strangest experimental monoplanes sponsored by the Air Ministry was the Parnell Prawn flying boat. Built to Air Ministry specification 21/24 of 1924 it had a protracted development, having its first flight in 1930. It is thought to have been part of a programme to produce aircraft that could be stored onboard submarines such as the ill-fated M2. The Prawn's most peculiar feature was having its engine mounted in a pod that could be pivoted upwards by 22 degrees to keep the propeller clear of the water during take-offs and landings.The principal was later used on the rear pusher engines of the Dornier Do 26 flying boat.

Another Parnell research monoplane commissioned by the Air Ministry was the "Parasol" (AM Specification 15/28). Two were built to study different aerofoil sections.

The Air Ministry wanted to see if a lightweight, all-metal aircraft with a small engine could replace the Fairey Flycatcher carrier fighter. In 1925 they issued specification 17/25 and selected a biplane design from Avro, the Type 584 Avocet, and a monoplane from Vickers (pictured above) the Vickers Vireo. Both the biplane and monoplane had all-metal construction and were powered by the same 230-horsepower AW Lynx engine. They both had an armament of 2 machine guns. The Avocet biplane ended up being 15 mph faster than the Vireo monoplane (135 mph v 120 mph). The Vireo had alarming stalling characteristics, largely caused by interference drag at the wing roots.

If the Air Ministry was prejudiced against monoplanes and thought them dangerous what were they doing putting the heir to the throne in one? The Air Ministry purchased a Vickers Viastra metal monoplane for the use of Edward, Prince of Wales. It first flew in 1933 and was used by the Prince for about a year. It was deemed unsatisfactory because of the high noise level in the cabin (this was despite efforts to soundproof the aircraft). It was passed on to the RAF where it was used for the experimental testing of new radio equipment. This was not the first monoplane provided for Edward, a Westland Wessex tri-motor high-wing monoplane (registration G-ABEG) was used by him from 1931 until 1933.

The Air Ministry wanted to see if a lightweight, all-metal aircraft with a small engine could replace the Fairey Flycatcher carrier fighter. In 1925 they issued specification 17/25 and selected a biplane design from Avro, the Type 584 Avocet, and a monoplane from Vickers (pictured above) the Vickers Vireo. Both the biplane and monoplane had all-metal construction and were powered by the same 230-horsepower AW Lynx engine. They both had an armament of 2 machine guns. The Avocet biplane ended up being 15 mph faster than the Vireo monoplane (135 mph v 120 mph). The Vireo had alarming stalling characteristics, largely caused by interference drag at the wing roots.

If the Air Ministry was prejudiced against monoplanes and thought them dangerous what were they doing putting the heir to the throne in one? The Air Ministry purchased a Vickers Viastra metal monoplane for the use of Edward, Prince of Wales. It first flew in 1933 and was used by the Prince for about a year. It was deemed unsatisfactory because of the high noise level in the cabin (this was despite efforts to soundproof the aircraft). It was passed on to the RAF where it was used for the experimental testing of new radio equipment. This was not the first monoplane provided for Edward, a Westland Wessex tri-motor high-wing monoplane (registration G-ABEG) was used by him from 1931 until 1933.

It was largely a given that the increasing power of aero engines would enable speeds where the added parasitic drag of a biplane would become unacceptable and that monoplanes must, at some stage, begin to predominate, particularly if the monoplane wing could become entirely self-supporting, without the added drag of wires or struts. Advances were made during the 1920s, thick-winged monoplanes with internal structures of metal were built, but their increased weight meant they did not show any advantage in performance over biplane types. For example, the Beardmore Inflexible was so heavy it could not carry any useful load.

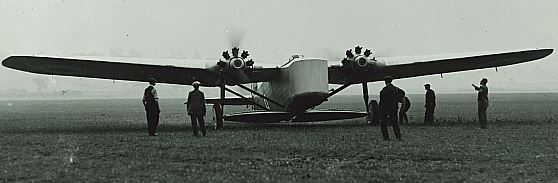

The huge Beardmore Inflexible was credited with being a bomber at the time, in fact, it was only intended as a one-off research aircraft. Its protracted development (ordered in 1923, first flight in 1928) was paid for by the Air Ministry. Note that it required a thick cable under the wings to prevent them from folding up in flight. Although the Inflexible was skinned all over with duralumin alloy, only the central core of the wings had what could be called a stressed-skin structure (and a very thick one at that). Any passengers carried on the Inflexible were expected to constantly scan the internal structure and wings for signs of structural failure!

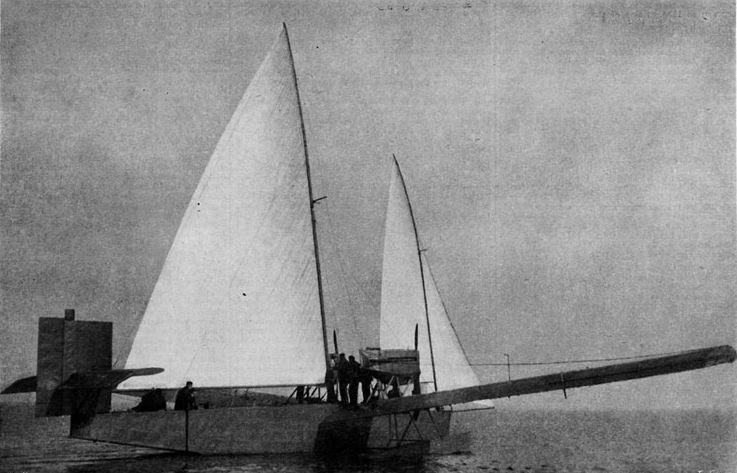

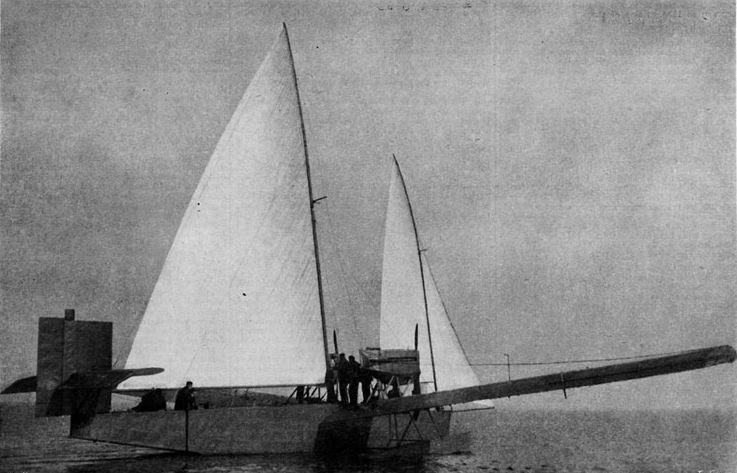

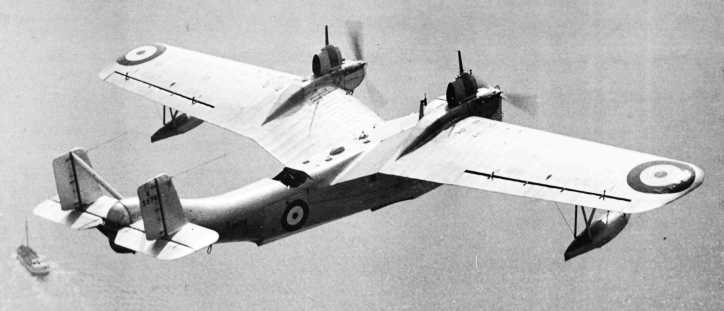

The equally huge Beardmore Inverness flying boat (Rohrbach Ro IV). A parallel project to the Inflexible, they were built using construction methods developed by the German Adolf Rohrbach, who had set up a factory in Denmark after World War One to manufacture his designs. The first Inverness was built in Denmark, the second was built by Beardmore in Scotland. Testing showed poor performance and handling compared with contemporary biplane flying boats. Again, the project was bankrolled by the Air Ministry.

One of the more unusual features of the Rohrbach Ro IV were telescopic masts so that the flying boat could be sailed home in the event of engine failure!

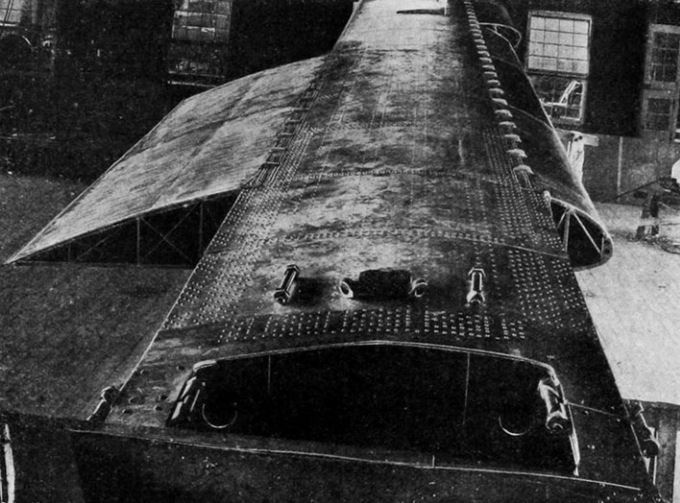

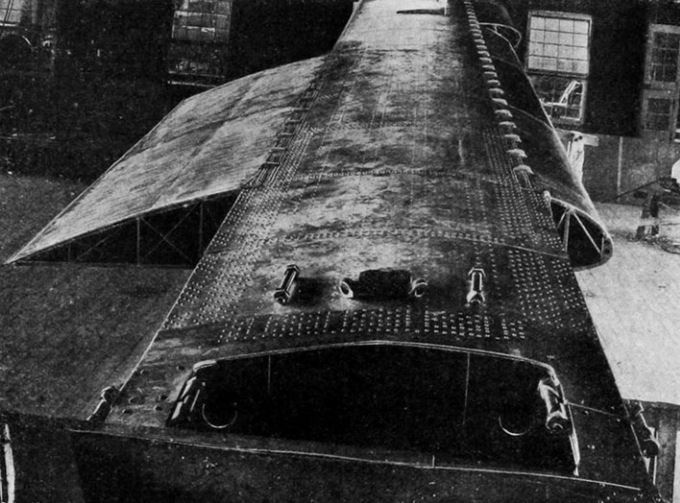

A typical Rohrbach wing construction as used on the Beardmore Inflexible and Inverness. You can see the heavy plating along the central section of wing to form a simple set of self-supporting metal boxes, a very crude method of stressed skin construction. Only this central section had a stressed skin, the leading edge and a large section of the trailing edge of the wing were constructed with traditional internal bracing trusses, albeit the wing was covered in duralumin rather than fabric.

The equally huge Beardmore Inverness flying boat (Rohrbach Ro IV). A parallel project to the Inflexible, they were built using construction methods developed by the German Adolf Rohrbach, who had set up a factory in Denmark after World War One to manufacture his designs. The first Inverness was built in Denmark, the second was built by Beardmore in Scotland. Testing showed poor performance and handling compared with contemporary biplane flying boats. Again, the project was bankrolled by the Air Ministry.

One of the more unusual features of the Rohrbach Ro IV were telescopic masts so that the flying boat could be sailed home in the event of engine failure!

A typical Rohrbach wing construction as used on the Beardmore Inflexible and Inverness. You can see the heavy plating along the central section of wing to form a simple set of self-supporting metal boxes, a very crude method of stressed skin construction. Only this central section had a stressed skin, the leading edge and a large section of the trailing edge of the wing were constructed with traditional internal bracing trusses, albeit the wing was covered in duralumin rather than fabric.

By the end of the 1920s, advances were being made in both materials and design techniques that started to make cantilever monoplanes practical, although for large designs this usually involved having to have a very thick wing with internal bracing wires and struts. With the added weight of these thick wings, they had little advantage over biplane types.

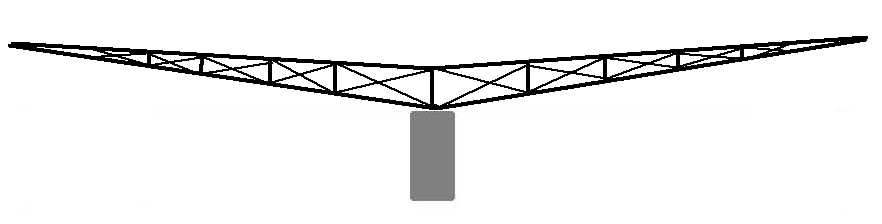

The internal structures of these thick-winged monoplanes were dependent on internal, stressed struts and wires, similar to the bracing between the top and bottom wings of a biplane.

Built to a 1927 Air Ministry specification (33/27) for a long-range mail carrier, the Fairey Long Range Monoplane had huge, thick wings.

The Fairey Hendon bomber utilised the thick wing design pioneered on the Long Range Monoplane. Its development was fully funded by the Air Ministry. It became the first monoplane bomber to enter service with the RAF although it showed no advantage over the contemporary Handley Page Heyford biplane bomber. Its introduction into service could only take place once the RAF had airfields big enough to cope with its long takeoff and landing runs and hangars big enough to accomodate its 101 feet 9 inches (31 metres) wingspan. One old RAF fitter once told me the Hendon was "Not so much a monoplane, more a biplane with the gap between the wings filled in!"

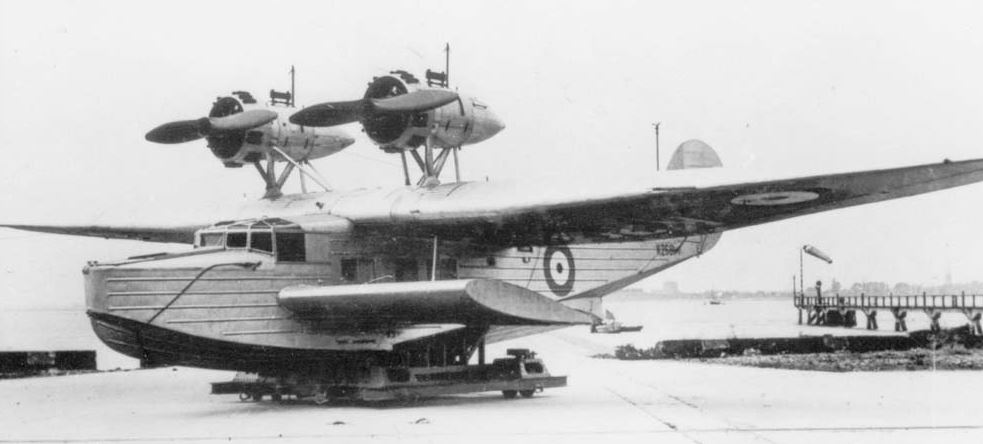

Another thick-winged monoplane ordered by the Air Ministry was the Blackburn RB2 Sydney flying boat. Built to a 1927 specification (R5/27), its wings had a duralumin structure covered in fabric, except for metal walkways next to the engines. The heavy weight of the thick wing meant it had a marginal performance and the single prototype suffered from bad serviceability during testing. It first flew in July 1930.

One monoplane winged flying boat that the Air Ministry spent a lot of money on was the Supermarine Type 179, sometimes called "the Giant". It was to have had six Rolls-Royce Buzzard engines mounted over the wing, carry 40 passengers and a crew of 7. Construction of the prototype was well advanced when the UK "National" government (elected in 1931 to sort out the financial crisis following the Great Depression) cancelled the project as part of a round of spending cuts. This is the final layout of the Type 179, with tapered wings and three rudders. Supermarine's chief designer, RJ Mitchell, had earlier considered using an elliptical wing layout on the Type 179, prescient of his later Spitfire design.

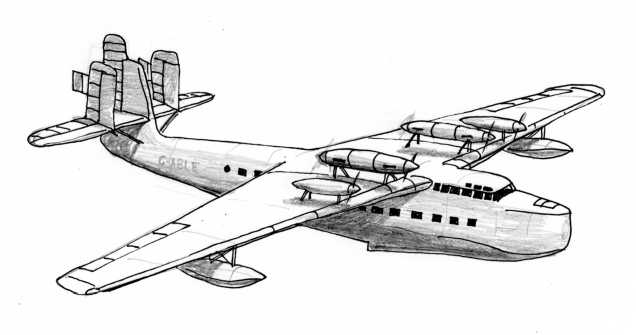

The Air Ministry ordered the trimotor Short S.11 "Valetta" monoplane floatplane against specification 21/27. It was intended to allow a comparison between the performance of a monoplane floatplane and the Short's S.8 "Calcutta" biplane flying boat (which was powered by three of the same type of engines). The Valetta first flew in May 1929. The evaluation revealed the biplane Calcutta to have a longer range and greater load-carrying capacity, while the Valetta was some 17 mph (27 kph) faster and had a better rate of climb. After this analysis, the Valetta was used by Sir Alan Cobham for a 12,300-mile (19,795 km) aerial survey of Africa. Then it was stripped of its floats and fitted with wheels for further testing as a landplane. After that, it was used as an airborne radio research laboratory. The Valetta ended its days as an RAF ground instructional airframe.

Another thick-winged monoplane ordered by the Air Ministry was the Blackburn RB2 Sydney flying boat. Built to a 1927 specification (R5/27), its wings had a duralumin structure covered in fabric, except for metal walkways next to the engines. The heavy weight of the thick wing meant it had a marginal performance and the single prototype suffered from bad serviceability during testing. It first flew in July 1930.

One monoplane winged flying boat that the Air Ministry spent a lot of money on was the Supermarine Type 179, sometimes called "the Giant". It was to have had six Rolls-Royce Buzzard engines mounted over the wing, carry 40 passengers and a crew of 7. Construction of the prototype was well advanced when the UK "National" government (elected in 1931 to sort out the financial crisis following the Great Depression) cancelled the project as part of a round of spending cuts. This is the final layout of the Type 179, with tapered wings and three rudders. Supermarine's chief designer, RJ Mitchell, had earlier considered using an elliptical wing layout on the Type 179, prescient of his later Spitfire design.

The Air Ministry ordered the trimotor Short S.11 "Valetta" monoplane floatplane against specification 21/27. It was intended to allow a comparison between the performance of a monoplane floatplane and the Short's S.8 "Calcutta" biplane flying boat (which was powered by three of the same type of engines). The Valetta first flew in May 1929. The evaluation revealed the biplane Calcutta to have a longer range and greater load-carrying capacity, while the Valetta was some 17 mph (27 kph) faster and had a better rate of climb. After this analysis, the Valetta was used by Sir Alan Cobham for a 12,300-mile (19,795 km) aerial survey of Africa. Then it was stripped of its floats and fitted with wheels for further testing as a landplane. After that, it was used as an airborne radio research laboratory. The Valetta ended its days as an RAF ground instructional airframe.

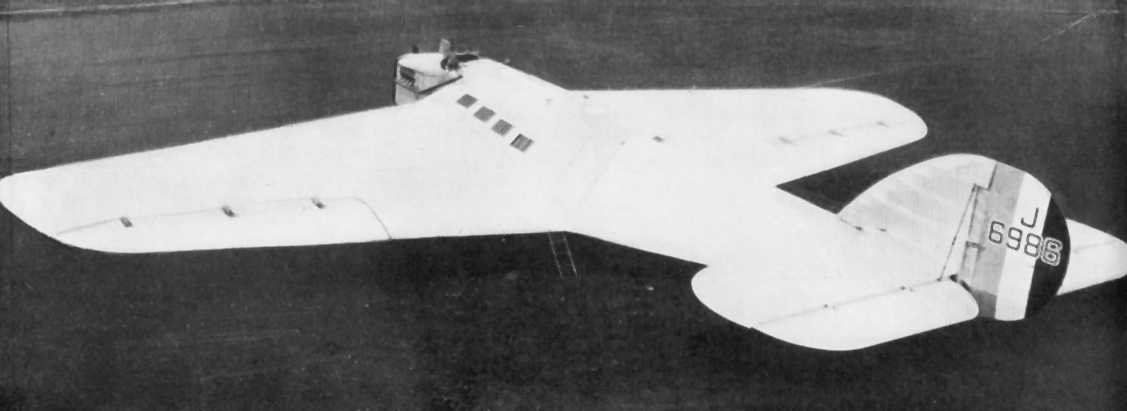

In 1928, the Air Ministry went as far as asking the Blackburn Aircraft company to build a biplane and monoplane that both had the same type of engines, fuselage, and landing gear so that a direct comparison could be made. The 1928 specification (18/28) was refined the following year (6/29), and the two aircraft first flew in 1932. Although their wings had an interior metal structure, they were covered in fabric. Surprisingly, the monoplane had slightly more wing area than the biplane, its wing having a longer chord and length. They had very similar performances, with the monoplane being marginally faster and having a higher ceiling. However, the heavy weight of the monoplane's wing meant the biplane could lift a much greater weight of cargo (2,500 lb compared to the monoplane's 1,500 lbs). By the time the two aircraft were evaluated, a revolution in stressed-skin aircraft construction had taken place, so the results were inconsequential.

The ten-passenger Blackburn CA15C biplane and monoplane. Built for a direct comparison of the benefits of monoplane design; there was little to choose between them. After the trials, the biplane was quickly scrapped but the monoplane saw service for trials of radio equipment and was much in demand as an aerial taxi, ferrying RAF officers home for weekend leave from Northolt aerodrome near London.

That revolution took place at the end of the 1920s when many new technologies came together to make the true cantilever monoplane jump ahead of biplane designs in terms of performance and economy.

Firstly, the design of flaps and leading edge slats evolved to the point where they were dependable. Coupled with more efficient aircraft brakes this made the landing and take-off runs of monoplanes shorter, opening up smaller landing grounds for monoplane operation. By the mid-1930s, a growing realisation that aircraft sizes and speeds were only going to increase meant that the Air Ministry finally bowed to the inevitable and started to plan larger airfields with concrete runways, with all the added expense that entailed.

Secondly, commercially available aero engines started to approach 800 horsepower with the promise of 1,000 horsepower and above. Increased engine power led to increased speed. Increased speed led to increased parasitic drag, which meant the drag-reducing monoplane format became increasingly desirable. Also, as the power-to-weight ratio of fighter aircraft increased the power of the engine began to have much more of an impact on the rate of climb, slowly eclipsing the advantage of biplanes in this area. Improvements in superchargers to give greater power at height accelerated the trend.

Lastly, and most importantly, the availability of thin sheets of Alclad, duralumin-like alloy with an outer layer of pure aluminium to resist corrosion, suddenly made possible stress-skinned designs; in these the metal skin of the aircraft wing itself forms a major part of the cantilever structure of the wing. This made monoplane wings much lighter and without the need for internal bracing, opened up the interior of wings to accommodate fuel tanks and retracting undercarriages. At the same time, it was found that advances in glue technology and denser sheets of plywood made wooden stressed-skin construction possible.

On the brink of the introduction of these new technologies, the Air Ministry paid for the construction of the Short S.18 Knuckleduster flying boat (first flight November 1933). Although the fuselage of the Knuckleduster was skinned in Alclad, the thick, internally-stressed wings were covered in fabric. On evaluation it was found to be inferior in performance and handling to the biplane offerings of Saunders-Roe (the A.27 London) and Supermarine (the Stranraer). Although the money paid out by the Air Ministry for the Knuckleduster went a long way towards perfecting the methods used on the later Shorts Empire and Sunderland flying boats.

In 1934, with purse-strings loosened by the easing of the Great Depression and with more money available for military research to counter the rising power of Nazi Germany, the Air Ministry ordered two examples of the Bristol 138 high-altitude monoplane. This demonstrates the Air Ministry's confidence in monoplanes, despite all the previous aircraft that had gained the altitude record being biplanes. The Bristol 138 gained the world altitude record for Britain in September 1936 with a flight to 49,967 feet (15,230 metres). It increased the record the following June with a flight to 53,937 feet (16,440 metres). The lessons learnt would greatly help with high-altitude operations in WW2.

In 1934, with purse-strings loosened by the easing of the Great Depression and with more money available for military research to counter the rising power of Nazi Germany, the Air Ministry ordered two examples of the Bristol 138 high-altitude monoplane. This demonstrates the Air Ministry's confidence in monoplanes, despite all the previous aircraft that had gained the altitude record being biplanes. The Bristol 138 gained the world altitude record for Britain in September 1936 with a flight to 49,967 feet (15,230 metres). It increased the record the following June with a flight to 53,937 feet (16,440 metres). The lessons learnt would greatly help with high-altitude operations in WW2.

What is Stressed Skin Construction?

Stressed skin construction means that the outer skin takes some, or all, of the "stress" the object is subject to, contributing to its strength. This means that the inner bracing structure can be reduced to a minimum or done away with completely (in which case the resulting structure can be called a monocoque). One simple way to visualise this is to imagine what would happen if the skin of the aircraft was removed. The aircraft of the 1910s to 1930s, built without stressed skins, would still have a skeleton of wood or metal framing and bracing struts and wires that would retain the shape of the aircraft. The skeleton structure would stand up to being loaded with weights to represent the loads encountered in flight. If you took the skin off a stressed skin aircraft you would expect to remaining structure to either immediately collapse, or fall apart when loads were placed on it to simulate those imposed in flight.

The Bristol Boarhound biplane of 1927, shown stripped of it's fabric skin and the metal panels around the nose and upper fuselage. The internal skeleton is entirely metal. You can see that the structure is self-supporting and does not depend on the skin of the aircraft. You could not take the skin off a stressed-skinned aircraft in this way without it collapsing.

The claim for the first stressed skin aircraft is clouded by national sympathies and misunderstanding. To simply cover a wing with metal or plywood does not make a wing "stressed skin". At the same time, a stressed skin design that has to use a gauge of metal that is so thick that it adds so much weight that the wing might as well have been internally stressed can hardly be regarded as a success. The first really successful multicellular, metal, stressed skin aircraft was the American Northrop Alpha which first flew in 1930. It led directly to the Douglas DC2 and DC3 and also inspired other American airliner designs. Meanwhile in Britain, almost by accident the Bristol aircraft company also stumbled onto multicellular stressed skin design when Alclad was substituted for the fabric covering of a new multi-spar wing being designed for the Bristol Bombay bomber-transport. The strength of the Alclad allowed the internal wire bracing of the wing to be dispensed with.

The Bristol Bombay (first flight June 1935) was the first British aircraft to be designed with an entirely multicellular, stressed skin wing, although it was not the first to actually take to the air with one. The Air Ministry specification it was designed for (C26/34) specified only monoplanes would be considered. Even so, both Supermarine and Boulton Paul designed biplanes for the specification in the expectation that any monoplane put forward would fail. Showing that it was usually manufacturers that were wary of monoplanes, not the Air Ministry.